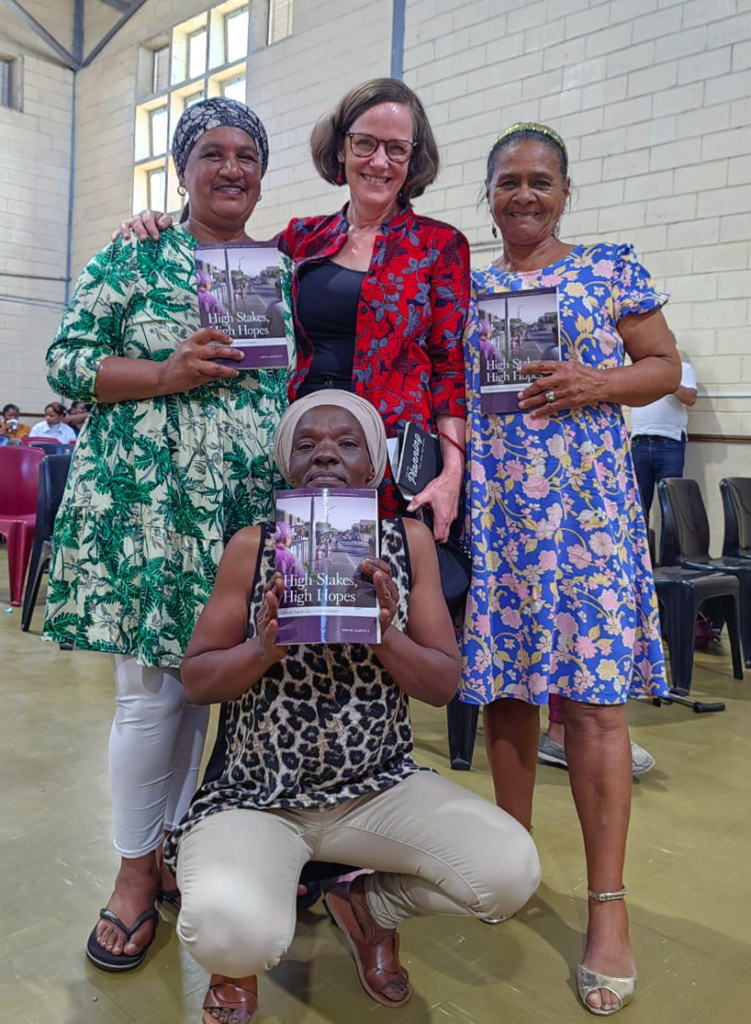

High Stakes, High Hopes: Urban Theorizing in Partnership (University of Georgia Press, 2023) by AAP’s Department of City and Regional Planning Chair and Professor Sophie Oldfield documents more than a decade of research and teaching done in collaborative partnership with the “Civic” (a local community organization) and its leader Gertrude Square in the Cape Town township of Valhalla Park. Rather than study community challenges at a remove, Oldfield built a partnership with Square and other activists in the neighborhood. Working together on research questions deepened the lessons and space they could share and document. Operating across the violence of durable South African apartheid divides and inequities, it opened up insight-filled paths for exploring complex urban issues. Presented in the text through reflective narrative and stories of collaboration, Oldfield captures the joyful, heartbreaking, and profound moments that came with the work and refigured the academic and on-the-ground impact of this approach to urban theorizing.

Molly Sheridan

What motivated you to dedicate your research to approaches to collaborative urban theorizing? Were there specific issues that you were seeking to address?

Sophie Oldfield

This book is rooted in Cape Town, a complicated, contested, unequal — as well as beautiful — South African city, like many in the Global South. In Valhalla Park, a formerly segregated “coloured” or mixed Black neighborhood, residents have to fight against evictions and for every right, service, and resource. They have rights on paper under democracy, but they still have had to fight for everything. These are layers that urbanists in South Africa and across the Global South study: How do cities manage? How do neighborhoods claim rights and engage and mobilize?

But in High Stakes, High Hopes, through partnership, there’s a third critical part: the place and role of the university. Our collaboration was built and run while I was working at the University of Cape Town, high up on the mountain slope, with a mission “to theorize the city and to teach its past and its present and to think about its futures.” But in South Africa — and in many places in the world today — the university’s legitimacy to do so is contested directly through societal and student mobilizations, which question: What is the university? What should it be doing? Who is teaching? As an urban scholar and professor, this period reshaped how my colleagues and I think about research: How do we theorize? How do we conduct research that is not extractive? How do we shape a city that is democratic, where people have rights and voices? For a neighborhood that was segregated and treated in so many violent ways, how do we reimagine research as participation and collaboration? The partnership between me, my university and students, and Gertrude Square and the Civic, worked in this problem space. It was a beautiful conjoining that I share and reflect on in this book.

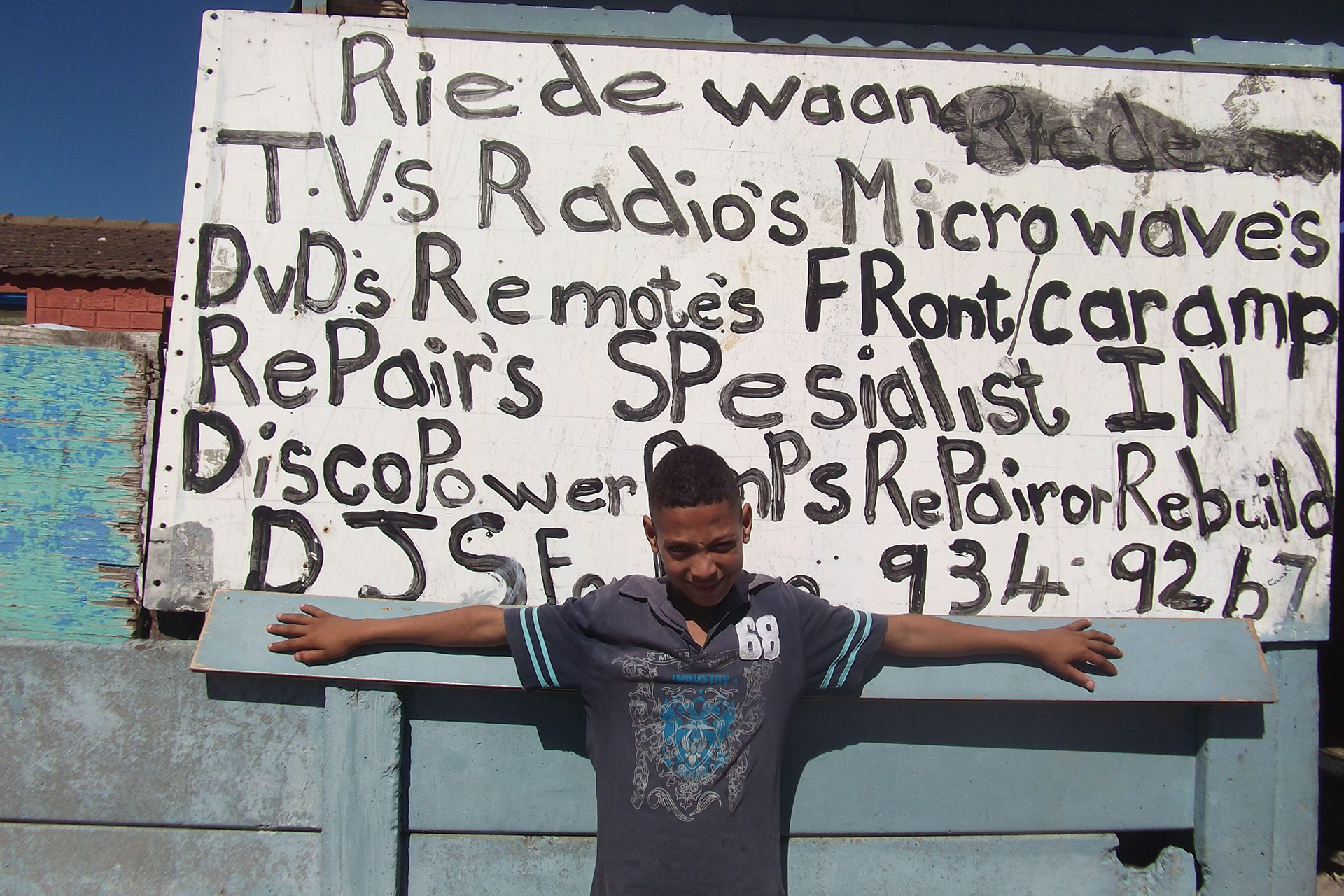

Teams of neighborhood-student researchers across the years of the partnership

Molly Sheridan

What were some of the most memorable moments in this process of working in partnership that shaped the course of your research?

Sophie Oldfield

High Stakes, High Hopes shares so many moments and processes, some which were dramatic and powerful, others banal, mundane, the day-to-day work of collaborating across a long period. Each chapter shares meaningful moments of meeting, working together, bringing in students to the partnership, sharing work in the community and city.

In the process of working, the students and I would spend half the time in the neighborhood and half the time in the classroom, and it made the experience deeply impactful. My partners taught students how you listen carefully, give integrity to somebody’s story, and build an understanding and theory of the city from that. There’s a really lovely phrase that collaborative work is always productively compromised. It’s never a romance or a recipe, but in it we might inhabit the difference between us. So, in the context of immense inequality, through collaborative work, we can figure out how to be in that space together and sometimes change things.

Molly Sheridan

You write about the challenges of inequality, conflict, and danger in working this way. How did you find it best to navigate those tensions and still effectively do the work you wanted to pursue?

Sophie Oldfield

All my partners were residents in the neighborhood, and they live with levels of violence that are still very challenging today. We could not have worked in this neighborhood — we would be suspect — if we weren’t in partnership with them or with other local organizations. We always worked in teams of neighborhood residents, activists, and students in various configurations. That was both a form of legitimacy, and it’s also what allowed us to be safe. Even still, sometimes conflicts arose and we had to pause and figure out how to go forward.

There were moments in our project, for instance, around xenophobic violence, personal violence, terrible experiences that reshaped families and lives. These tensions and traumas that also often include gangsterism, segregation, racism, racialization, stigma, and housing and livelihood insecurity, are realities that residents navigate all the time. The partnership was a means through which we could work together to “inhabit” the inequality that divided us, and to sometimes address and reshape it.

But there’s also a level of violence in how scholars theorize, right? The term “epistemological violence” reflects the limits and problematics of how we know, how we write, the ways in which we build policy and theorize. Our collaboration created a space in which these assumptions were challenged and turned into questions that we could engage and respectfully figure out how to have conversations together. In these very real moments, across a decade, the project didn’t solve or address any sort of material inequalities, but it allowed us to discuss and to be present in that mix.

Molly Sheridan

What lessons have you carried out of this work? I know you’ve mentioned its impact on how you teach…

Sophie Oldfield

I found it to be an absolutely brilliant space in which to teach. My partners — residents, activists, mothers, daughters, sisters — were teachers just as much as me. The process over this decade challenged us all to refigure how we think about the city and how we imagine change in the city. In the book, I reflect on how we built a way to ethically engage across difference and inequality. For me, that’s at the heart of what we’re doing here in City and Regional Planning and Urban Studies. Finding ways to work in and beyond the university to engage and address the many urban problems that shape our world — building ways to know better and ways to help students learn in an ethos of collaboration and participation. A joy of teaching together was seeing students develop confidence and find their voice, but in a careful, ethical, and collaborative way.

We have lots of examples of these forms of engaged work at Cornell. In all of it, I feel that a commitment to reflection and the learning process, its ethics, and methods is key. Through partnerships — and many forms of collaboration — we can ensure that our urban work is relevant, rigorous, and that it engages carefully with, in my case, neighborhood groups, activist groups, and those who are really struggling against all sorts of powerful forces in cities. We work together so that those ordinary people who make the city have a voice and can be heard. In turn, “urban theorizing in partnership” offers ways for urbanists to engage the city, its substance, its stories, its everyday contradictions and possibilities. It offers forms of practice, grounded in teaching, to train the next generation of urbanists to understand and engage the city and its urban futures. Through collaboration we can in small and incremental ways reimagine the university, its mission, and its mode, embedded in multiple publics and politics across the city.

***

CRP Chair Sophie Oldfield’s book High Stakes, High Hopes: Urban Theorizing in Partnership is one of many recent faculty publications that will be featured during AAP’s annual Launchpad event on March 19, 2025. Launchpad is held in Milstein Hall and is free and open to the public. The event includes presentations by the authors, as well as a reception with opportunities to peruse and purchase many of the publications.