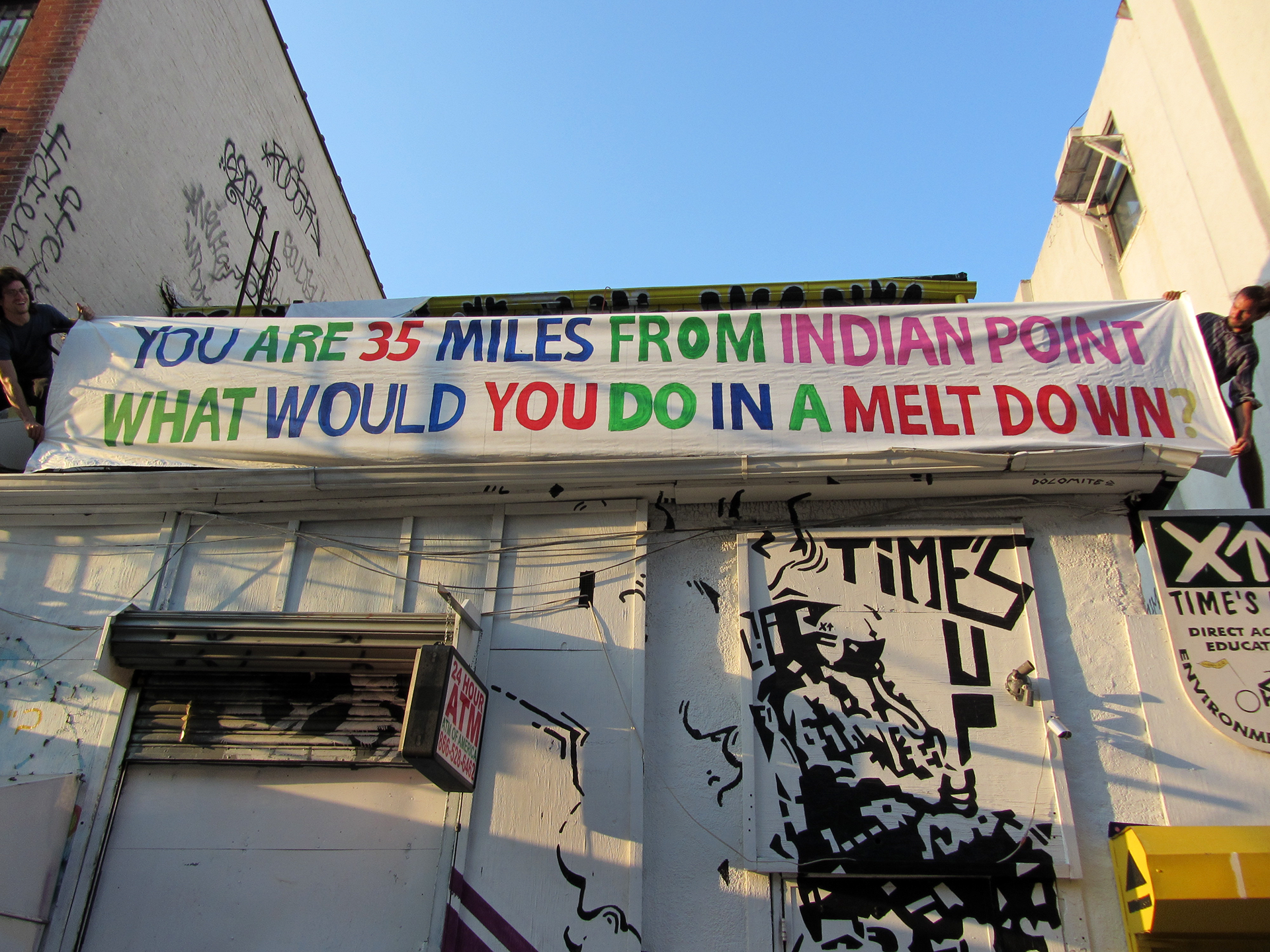

From its opening in the 1960s until the shutdown of its last reactor in April 2021, Indian Point was a site of promise and tension. Surrounded by the bucolic landscape of the Hudson Valley, the nuclear plant generated high-paying jobs and carbon-free power for an energy-hungry New York City only 35 miles down the river, yet concerns about pollution, accidents, earthquake risk, and the aging infrastructure of the facility — especially one in such close proximity to the largest city in the U.S. — fueled a protest movement that dogged the plant throughout its life. Now that it has ceased operations, however, achieving the state's renewable energy goals presents new challenges and the property remains a storage space for spent nuclear fuel with no relocation options currently available.

Embodied Power at the River's Edge: Reimagining Indian Point

How do you solve a problem like a massive decommissioned nuclear power plant only 35 miles north of New York City with no clear future use? This semester, an architecture option studio at the Cornell Gensler Family AAP NYC Center is tackling this very question, imagining an evolution for the facility rather than a demolition.

Aerial view of Indian Point Energy Center on the Hudson River in Buchanan, New York. image / Alamy Stock Photo

What happens to a building when its original purpose disappears? Other than becoming a costly landfill, what alternative paths exist to give such structures their next lease on life?

These are the kinds of questions that HALF – LIFE, an option studio co-taught by Architecture Professor of the Practice Florian Idenburg and Lecturer Jonathan Molloy (both of the architecture and design firm SO – IL), is exploring with twelve undergraduate and graduate students studying at the Gensler Family AAP NYC Center this semester as they consider the adaptive reuse potential of the Indian Point Energy Center.

"The studio asks students to consider the relationship between energy, material, and experience," Idenburg explains. "It's a complex studio dealing with expansive concepts of time. The outcome of the studio is very diverse. Students are picking up on different things and developing a variety of ideas, all proposing alternate futures for this complicated site along the Hudson River."

A 22' sign created for Time's Up's Bike & Sail Action to Shut down Indian Point on August 9, 2011. image / Peter Shapiro (CC BY-SA 2.0)

On a grey day last February, it was with this context in mind that the studio visited the plant's 240-acre property, now owned by Holtec International, a New Jersey decommissioning firm. Holtec's work of the past two years has primarily focused on the de-fueling of the plant (a process also not without contention) and the built structures have so far been left largely untouched.

The Spring 2023 Option Studio HALF – LIFE tours the immense spaces that make up the Indian Point Energy Center. images / Muskaan Chugh (B.Arch. '24) and Jonathan Molloy

The Spring 2023 Option Studio HALF – LIFE tours the immense spaces that make up the Indian Point Energy Center. images / Muskaan Chugh (B.Arch. '24) and Jonathan Molloy

The Spring 2023 Option Studio HALF – LIFE tours the immense spaces that make up the Indian Point Energy Center. images / Muskaan Chugh (B.Arch. '24) and Jonathan Molloy

"It's a very interesting opportunity to think about adaptive reuse, which is a very important type of architecture these days," notes Molloy, who grew up in the Hudson Valley and vividly recalls the controversy that surrounded the high-security site. "The most sustainable buildings you can make are the ones you don't have to build, so if you can use buildings that already exist, you can use the embodied carbon that has already been extracted from the earth to make new spaces. These are some really enormous, robust structures and a really potent site to think about what it means to reoccupy a space and using the infrastructure that's already there for some form of new life."

"Seeing these structures up close was a powerful experience," says Gabriella Kim (B.Arch. '24). "I had never done an adaptive reuse project before, let alone set foot in a nuclear power plant. I thought this opportunity to not only visit the site but to also engage with it down to every single detail would be an amazing opportunity. Based on my experience this semester, everything has aligned with my expectations; the moment we approached the giant reactors — 200 feet tall — will stay with me forever."

The literal enormity of the challenge ended up being a powerful lesson in and of itself as students worked to encompass everything about the site in their plans before realizing that part of the challenge might be letting some of it go. This led to discussions about the history of the buildings related to energy and consumption, as well as considerations of the site's larger ecology. Molloy equated tackling such a nuanced and difficult project to "running with weights on," emphasizing the value of such an exercise. "Even if the end result is less developed than you might have aspired to, it's valuable in the way that it has trained you to take on something that's more than you might have been prepared to do."

The studio asked students to first consider the design of a large-scale event in the space before tackling a more permanent-use proposal. Additional trips to locations such as DIA Beacon, an art gallery housed in a converted former Nabisco box-printing facility, and Brooklyn's Powerhouse Arts, a renovated 117-year-old power plant that now serves as a contemporary art center, encouraged the students to further expand their thinking about what was possible and how their own projects might develop.

Is there a next possible use for these structures worth imagining? At the very least, these are the types of questions studio participants hope to encourage more and more people to ask. image / Jonathan Molloy

Shengkun Yang (M.Arch. '23) took a lot from these discussions and exercises, which encouraged zooming out and "seeing the bigger, more inclusive picture," lessons that will be carried forward into future work. "In the short term, it really opened our minds to novel and unique adaptive reuse programs yet to be explored by our industry," Yang acknowledged. "In the long term, it teaches us the importance of understanding the fuller picture. A mature proposal can only be designed when we understand that the problems we identify are often just a faceted representation of a wider, tightly knitted web of social, economic, and cultural agencies enacted by multiple actors."

For Indian Point, the site's story is still being written and the next chapter isn't yet clear. While no one is expecting that the buildings will be kept as they stand, the studio is excited to welcome Richard Burroni, Holtec's Site Vice President overseeing the decommissioning work, to their final review and hopefully inspire some alternative thinking about the possibilities presented by the existing site. Is the only option worth considering tearing everything down for new development? Is there a next possible use for these structures worth imagining? At the very least, these are the types of questions studio participants hope to encourage more and more people to ask.

As the course evolved over the semester, "it certainly revealed what we suspected," says Molloy. "It seems like an immense opportunity for the region that could be a really exciting, beautiful story of bringing a place that has been extractive for a long time back into the fold of the Hudson River region."