Building Pathways: Lessons in Collaborative Instruction and Community Engaged Design

This semester, a compelling conversation across architecture, landscape architecture, and planning has been made possible through the collaborative strategies of three AAP studios focused around work in Salamanca, New York.

This spring semester, three classes spread across architecture, landscape architecture, and planning intersected around the same site: Salamanca, New York, a city within the Allegany Territory of the Seneca Nation of Indians. Acknowledging overlaps in subject matter and approaches to engagement, CRP Associate Professor of the Practice George R. Frantz, CRP Lecturer Mitch Glass, and Architecture's Preston Thomas Memorial Visiting Associate Professor Anna Dietzsch made a point of integrating their students through combined discussions and field trips so they could exchange information and ideas among themselves and ultimately with their partners in Salamanca.

However, before the development of proposals addressing area infrastructure issues and revitalization efforts would even be possible, the students and instructors had to build avenues of communication and trust with community stakeholders. The diversity of cultural and design perspectives involved required sensitivity and awareness that stretches beyond the primary subject matter. The resulting projects demonstrate the power of collaborative learning opportunities beyond the classroom, illuminating pathways towards more advanced design discussions while also delivering actionable plans ready for implementation.

1

This is a compelling triangulation of architecture, landscape architecture, and planning discussions focused around Salamanca, New York, and its environs. While the city is facing issues common to the Rust Belt, it's also unique due to its location within the Allegany Territory. Would you begin by telling us just a bit about the work and goals of each of your individual studios?

George R. Frantz: My CRP Land Use and Environmental Planning Field Workshop is completing two planning projects for the Seneca Nation of Indians (SNI). The first is a walkability study for the city of Salamanca within the Allegany Territory, which involves an assessment of the scope and condition of pedestrian infrastructure in that city. The second project is a trails plan for the areas of the Allegany Territory outside the city. The objective of this project is to lay out a system of multiple-use trails that will connect the outlying communities with Salamanca, while also providing access to hunting and fishing sites. Both plans will be written with the intention that they can be implemented by the community.

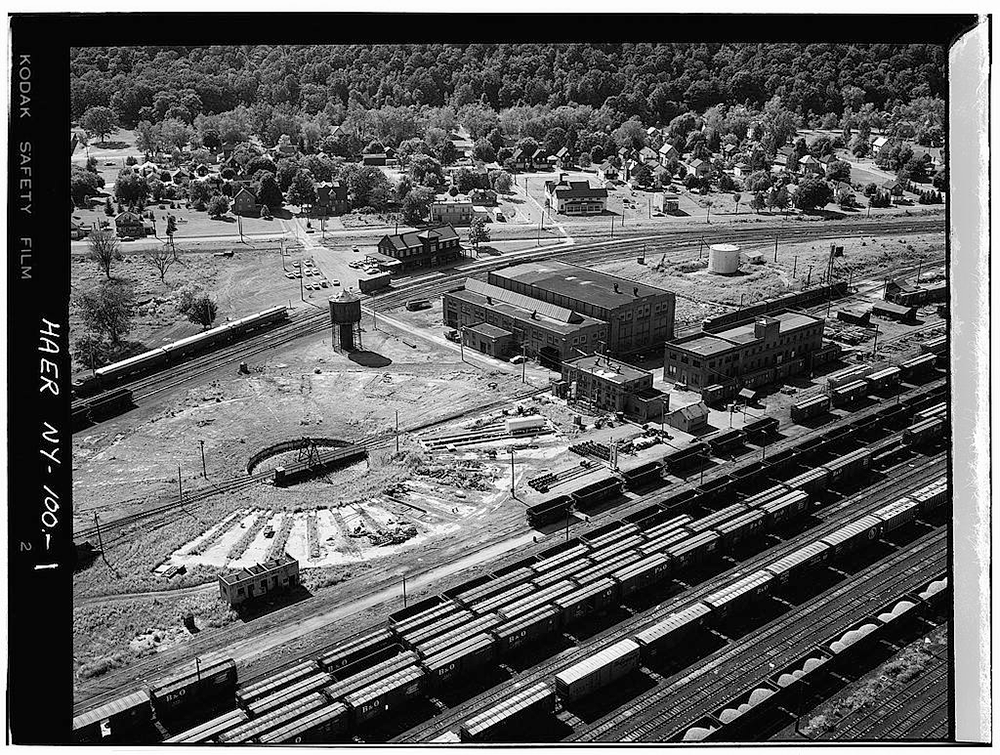

Mitch Glass: The second-year, second-semester studio is for sophomores majoring in Landscape Architecture (LA). Up to this point, they have focused on design fundamentals and design theory, while addressing smaller, more focused sites in a conceptual way. This studio is asking them to work on a much more complex design challenge for a specific partner (Seneca Nation) while utilizing and developing the analytical and design skills they've been practicing so far. Beginning with readings about Haudenosaunee culture and the Seneca Nation more specifically, students turned their attention to landscape analysis at the regional and city scale (Allegany Territory and Salamanca, respectively), followed by site-specific analysis of the city's ~60-acre former railyard. They then developed landscape and ecological programs for this site, dealing with profound layers of historical use (indigenous, colonial, and post-industrial), current soil and vegetation conditions, speculative work on viable land re-use and rehabilitation processes, and aspirational but feasible suggestions for use of the railyard. These included ideas for local and regional trail connections, gathering spaces, community agriculture, active and passive recreation, and many other potential programs.

Anna Dietzsch: The Expanded Practice Option Studio is open to fourth- and fifth-year architecture undergrads and graduate architecture students. The studio is framed as "an invitation to address structural change to systemic social-spatial issues underlying the current environmental crisis through the acknowledgment of the indigenous presence in the region." Working between different scales, students were asked to critically assess the embedded layers of regional infrastructure and systems of power in place and produce a StoryMap. Based on this initial approach, students elaborate a "thesis" and a "question" that will substantiate their design which can be at the urban or architectural scale. Projects have put forward ideas such as an art park inspired by the traditional longhouse, and a food hub with a farmer's market and stores to help bring healthy food options to Salamanca.

2

How does collaboration across your disciplines illuminate intersections of theory and practice across planning and design?

GF: The objective of the Land Use/Environmental Planning field workshop has historically been to bridge theory and practice through projects that deliver a usable deliverable tailored to the needs of the community. In addition, the class is an interdisciplinary experiential learning opportunity, bringing together planning, landscape architecture, and natural resources / sustainability studies majors to work together on a project. In this particular project, however, history and culture become critical components of the practice.

AD: I don't believe we can afford anymore to think about architecture without a holistic understanding of the regional context, as we cannot design without a multiscalar approach. The idea of having a three-way collaboration is to explore different inputs coming from different disciplines. The exchange between George, Mitch, and I has been very fruitful, and the students have benefited directly from things like shared guest lectures, resources, and information, and they have benefited indirectly from our joint discussions and planning.

MG: Collaborating with planning and architecture students and Anna and George has provided windows into scales of thinking and theory and lines of inquiry that LA students would otherwise not be familiar with. LA students at this stage are gaining an understanding of the physical realm and ways of seeing / recognizing landscape patterns and places. Less developed are ways of seeing complex social and cultural relationships across time and place and how these impact our efforts to make positive and transformative change in the built environment. George and Anna have led lines of inquiry that seek to highlight and define these structures in a way that has enlightened my students toward deeper reflections (conceptually) and outcomes (tangibly).

3

All three studios quite explicitly seek design ideas that will build more environmentally and socially sustainable communities. How do these priorities align with the goals of the stakeholders you're engaging with in Salamanca?

GF: They align very well. The SNI today is dealing with the legacy of environmental contamination left by the Euro-American railroads and early oil industry. In violation of the 1794 Treaty of Canandaigua, the U.S. government in the 1960s flooded 1/3 of the Allegany Territory, including much of its best agricultural land, building the Kinzua Dam. Two centuries of state and federal policies have worked to disconnect them from the land. Today, they are working to restore that connection, restore their lands, and move toward a more environmentally and socially sustainable community

MG: The work of the studio aligns specifically with the goals of our partners in the Seneca Nation. Currently, in the process of taking ownership of the former railyard, they are seeking creative and innovative approaches to feasible re-use scenarios for the land. This includes approaches to brownfield remediation, as well as public space programs and connections to existing assets in the vicinity (Rail Museum, Salamanca Main Street, regional trails, etc.) of this critical site near the Allegany River.

AD: My studio differs from Mitch's and George's in that it is not responding to a direct concern or request from the SNI. Rather, we begin by critically assessing important questions and issues on a broader spectrum (historically and geographically), before offering answers through design proposals. In a way, its regional and open-ended approach engenders the discussion of long-term projects and ideas. The possibility of students interacting directly with stakeholders gives both the opportunity to balance out what these could be. The discussions we have had with SNI representatives have been enlightening for both us and them, I think.

4

Grappling with questions of culture and design, in this case between indigenous and non-indigenous perspectives, seems to offer both powerful opportunities and possible (and perhaps unforeseen) challenges. How does this inform how you guide your students? How does it impact the work your students do in the community and in your class/studio?

MG: We are very fortunate to be invited to the table to work for and with indigenous partners in the Seneca Nation. It is critical to understand that they are a sovereign nation, with their own social, political, cultural, and governance structures that have survived centuries of colonialism. So, when we collaborate on a project in the Allegany Territory (or with any Haudenosaunee people), it is imperative for students to recognize their position as Cornell representatives working in places with deep cultural histories, places with generational trauma, and in places and with people that are not "of the past" but exist in the modern world and who continue to seek sovereignty and justice in all its forms. Students need to continually reflect on this dynamic and to listen deeply to our project partners to achieve new understandings of indigenous culture and space.

AD: As is the case with the landscape and planning students in Mitch's and George's classes, architecture students working with indigenous communities brings to the table important pedagogical issues and discussions, including notions about identity, alterity, sovereignty, and of course colonization and power. Students are asked to face these issues and take a position about them in their designs, which is necessarily a challenging and powerful charge.

GF: To illustrate with an example that relates to the matter of facing issues, understanding difference, and listening intently, as Mitch and Anna mention — my field workshop students are charged with preparing a walkability study and a trails plan for the Seneca Nation. In the mainstream American planning context, trails are recreational amenities and the bicycle a toy, and ATVs and snowmobiles particularly obnoxious toys. In China and in Europe, bicycles and motorbikes are still integral parts of a comprehensive transportation system. In many Native American communities, ATVs and snowmobiles are useful modes of transportation. One of the opportunities for my class is to design a trail system for the Seneca Nation that connects the various communities in the Allegany Territory as an element of the overall local transportation system, including ATVs and snowmobiles.

5

Through your work with both the students and the community in Salamanca this semester, has your own research or practice been advanced in any notable ways?

GF: American planners and designers in general have a very cursory overview of the history of the places they work in, and very rarely venture outside the Euro-American cultural imaginary within which they live and operate. Preparing for this field workshop in the Allegany Territory required a different outlook, one that integrates Jocelyn Poe's communal trauma concept with the concept of land not as a commodity, but as a common resource for all, and also one which holds the collective memory of the people. I see these two themes running through the multiple treaties I researched, and through the history of dispossession of the millions of acres of land lost by the Seneca Nation since the Guswhenta Treaty of 1613.

AD: I have worked with several indigenous communities in Brazil and being able to work with the Haudenosaunee in New York has been a tremendous privilege. The opportunity to engage with the similarities and differences between these communities has been helpful for me to better understand the "indigenous imaginary," or what I've called "circular cultures." Learning about each community's strategies for adaptation in the face of historic violence and how they balance "indigenous" and "modern," keeping traditions and a strong sense of resiliency, is not only inspirational, but instrumental to my understanding of how hybrid systems could be used to bring together natural cycles and man-made action, the basis of what I've called the "Forest City" platform.

MG: Being able to work with the SNI and seeing students learn about and become acutely aware of Haudenosaunee and Seneca culture in this region has been a very rewarding experience. This is my second studio focused on indigenous landscapes and culture and each experience motivates me to do more to listen to indigenous voices and to fully understand, respond, and add value to the underlying complexities of this topic as a landscape architect.

Stay connected! Follow @cornellaap on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn; and subscribe to our AAP bi-weekly newsletter.