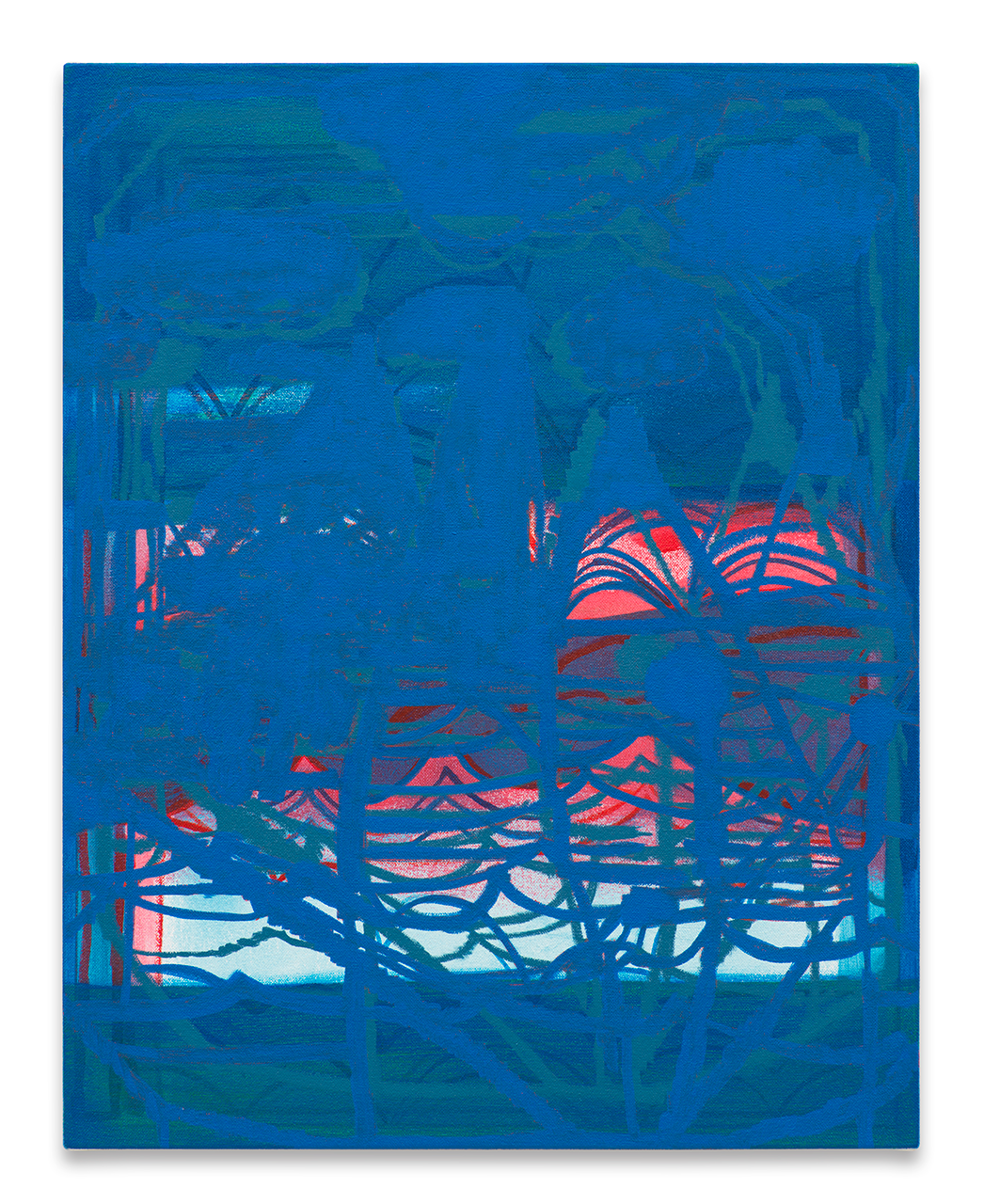

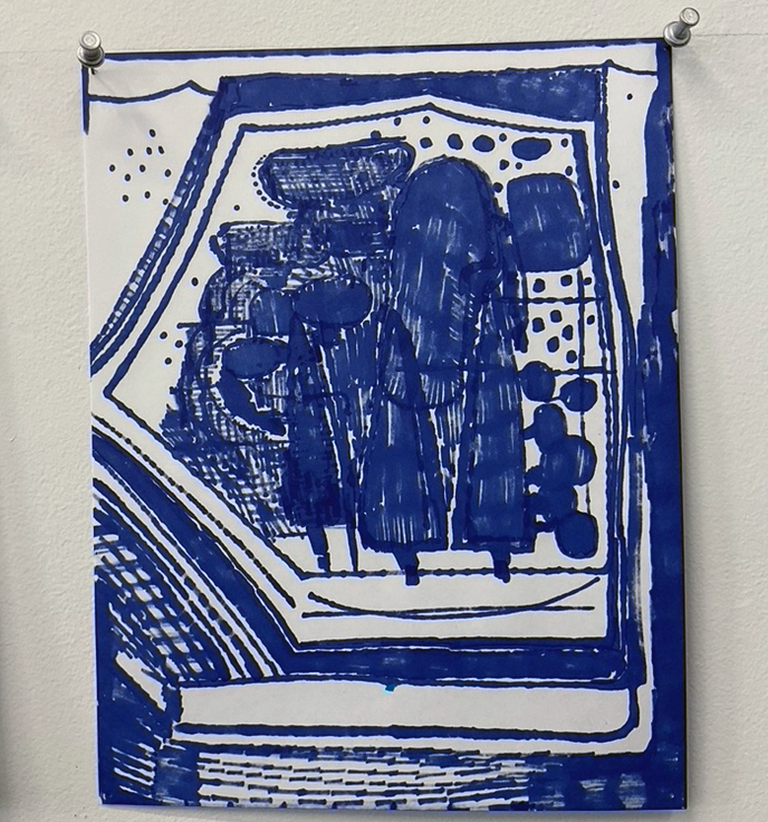

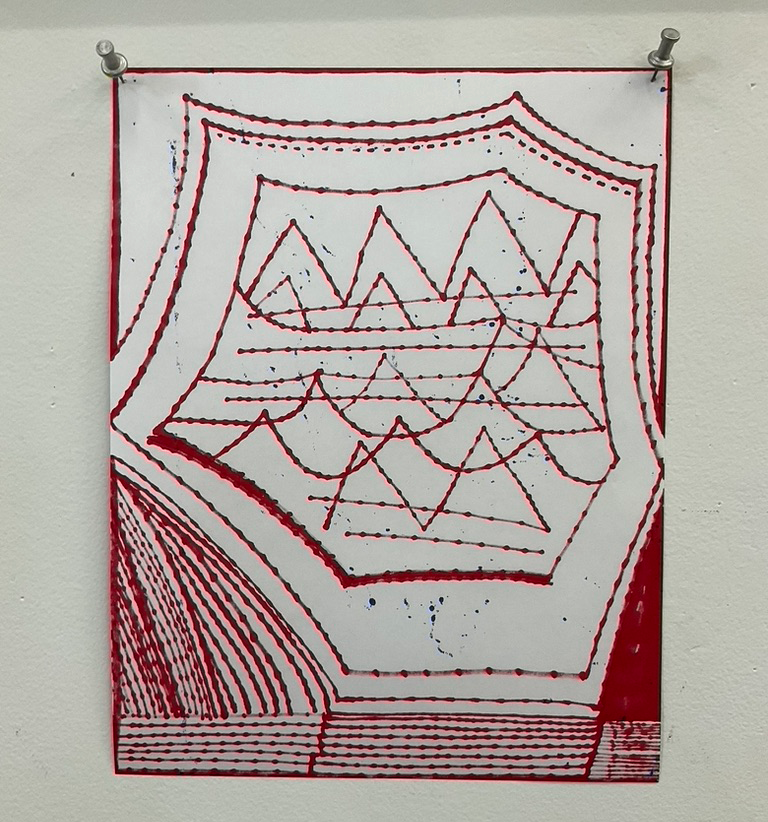

There’s a pixelated energy coming off EJ Hauser’s recent paintings through both shapes and color, yet also aspects of medieval marginalia of a sort that have been invited inside the confines of the canvases. Lions peer out at the viewer or birds perch in neat rows, trees and mountains vibrate. In conversation, Hauser is quick to underline the value they place on exploring the natural world through their work, as well as the necessity of holding on to wonder and a sense of play no matter how much experience they accrue.

From questions about content and process to insights into career paths, they have been offering encouragement and sharing their professional perspective with M.F.A. candidates in the Department of Art as the Fall 2023 Teiger Mentor and will discuss these topics with the broader AAP community during an artist talk on Thursday, November 30, at 5:15 p.m. in the Abby and Howard Milstein Auditorium. In preparation, Hauser offered some lessons learned through a life dedicated to painting.

Molly Sheridan

Would you share a bit about what has shaped your visual language? How has that developed?

EJ Hauser

The title of my upcoming lecture is “Mission to Explore,” and I came up with it after a conversation with an artist and seeing a Jacques Cousteau documentary. As a child, I thought Cousteau was interesting because he had this appetite for going into the natural world and trying to explicate the wonder he found. I thought about how this is an artist’s mission that is informed in childhood. Since children don’t have much experience, they can give themselves over totally to a world full of mystery, a world full of magic even. I want to feel this way about the world, that there is something that we can’t explain with words, something that’s a third thing. I think about poetry a lot. Poetry is made up of words, but it’s also about sensations and concepts, it’s a kind of abstraction. One of the things I love about art is that it doesn’t stay the same. A painting doesn’t move — the brush marks all stay in the same place — but you are always different when you’re looking at a painting, and so you become this interesting element in the story of what the painting means and how it’s apprehended.

It’s important for artists to keep this suspension of what’s real in order to give themselves over to the fantasy they are trying to portray. For me, it’s an exuberance about the natural world and how amazing that is, or creatures or words. I’m always combining those things in my work. This mission to explore is something that I also try to encourage my kids, my students, to take on — the ability to have the make-believe be important. Making a painting is playing, sort of. It’s taking materials and trying to find out what they can be besides just paint in a tube.

A painting doesn’t move — the brush marks all stay in the same place — but you are always different when you’re looking at a painting, and so you become this interesting element in the story of what the painting means and how it’s apprehended.

Molly Sheridan

How do you sustain that as you move through your career?

EJ Hauser

I had a smart person once tell me that artists need to build themselves a beautiful suit of armor and hang it on a hook right outside their studio. When you leave, you’re supposed to put this beautiful suit of armor on so that you don’t get dinged up in the world. Then, when you get back to the studio, it’s imperative that you take it off so that you have the vulnerability and curiosity to be that sensitive kid that you need to be in order to make the work that you need to make. I mean, it’s not all kid energy, but I think that there’s this spark of it that’s crucial to getting studio projects made.

I’ve been making paintings since I was 16, so this is decades of fooling around with materials and making stuff called art. It’s a kind of calendar in a way, a diary. If you lined up all the paintings, there would be a way, at least for me, to be in touch with the total journey as a human being. It is hard to keep connected to those things, but I think that if the origin point is always somehow to touch this exuberant, curious child, it’s this place you can check in with in your making.

Your question about how you continue to walk into your studio with the kind of juice that you need is something that I don’t think can be just self-sustained. I think it’s a communal effort, and I think that certainly my position here at Cornell is to try to give my dear students some of that juice to draw upon as they get older.

Molly Sheridan

As I learned more about your process, I was really struck by how your attraction to certain tools — brush shapes, types of paint — then of course impacts the finished piece. Do you stick to a specific set of tools like a musician might a single instrument to express whatever idea you’re working toward, or do you reconsider them?

EJ Hauser

For me, and many painters, there’s a huge affinity between color and music. I think I was a musician in every previous lifetime, and now I’m a painter. It’s a powerful sensorial experience inside of your ears that sets off chain reactions inside of your body. I’m interested in how things that human beings make can do that for other human beings.

I’ve been painting in oil for a long time, and after seeing the Henry Taylor show in Los Angeles — and having so many artist friends ask me, “Why always oil?” — I stared working with acrylics. I hadn’t painted with acrylic for years, but I was so convinced by what I saw on Henry’s canvases, I had to give it a try. What I found out was that, of course, materiality changes the broadcast out of an artist’s studio! Now I am in a place where I am putting acrylic and oil together on my canvas because they both offer me different ways to approach image making. Acrylic is a water-based medium, and there is something about the fact that you can control the opacity or the surface with water, and that adds a “weather” to my paintings that wasn’t there before. I’m also surprised by the colors I can get with acrylic. They’re adjacent to a sort of graphicness and my work has a graphic quality to it.

I often think about what I call urgency in art making. What time needs to be invested to provide something that the ear or the eye enjoys? I love a Matisse drawing with a piece of charcoal, just one line on the page. But then I also love a full symphony. In art broadly, I don’t have a material thing that I prefer, it could be anything. It all has to do with how the materiality goes along with what’s being expressed.

Molly Sheridan

But you yourself do tend to stick with a specific set of painting materials?

EJ Hauser

Yes, absolutely, because I know how to use those materials. One of the things I talk with my students about is that we are in an age of art making where a lot of people are thinking of themselves as multidisciplinary artists, making a painting and a film and a sculpture and a play and a podcast and a performance and a song. That’s amazing, but I’m also interested in the other end of the spectrum. I am curious to see what it’s like to have started painting at 16 and then paint, hopefully, until the day I die. It’s just a different kind of commitment to making. It’s like an experiment I’m doing — to continue to be a painter for my whole life and see what happens with the paintings.

Molly Sheridan

As this semester’s Teiger Mentor in the Arts, you’re working closely with AAP graduate students. What observations or guidance or even questions do you find yourself sharing with them in this context?

EJ Hauser

This is the first time I’ve had a title “mentor,” so before coming to Cornell this semester, I gave the word a great deal of thought. I ended up feeling so much gratitude for the mentors I’ve had in my life, and I arrived at something like the biggest thing I can offer the kids — I call them kids even though they’re all, like, 30 — is a great deal of encouragement, and try to be a good observer and listen to them.

As a mentor, I’m operating from my experience. When I review my past, I can’t believe the roads I’ve traveled and how lucky I have been. What most students want to know is how to have a life in the arts and how to keep having beautiful, interesting thoughts in their studios as they’re making their way out of school and into the real world. In my experience, every artist’s journey is quite unique, so the premise that one can teach eight amazing, individual artists here at Cornell how to be artists out in the world at large is a complex job.

But we have a great time trying, and we look at their subject matter and content, and talk about their formal concerns. One thing as a mentor that I’m invested in is not offering up solutions for how a mentee should resolve their studio “issues.” I believe the critique is about the critic, and when someone starts deconstructing and unpacking what it is that you’ve made, they’re talking about themselves and what they make, by and large. They’re talking about what they’re interested in. So, I always say at the beginning of any studio visit, full disclosure, I’m going to come in here and pretend to talk about your work, but I’m really talking about my work. But you do it with kindness and respect, and then try to listen and be a sounding board.

I feel like my job as a mentor is to connect kids to what’s undeniably important to them. I’m trying to encourage them to have a strong inner space so that when the world either accepts or rejects what they’re doing, they are okay either way. And to know that it’s a long road and that there are artists who make fantastic work that we’re never going to see, and that there’s less good work that we’re going to see all the time.

I feel like my job as a mentor is to connect kids to what’s undeniably important to them. I’m trying to encourage them to have a strong inner space so that when the world either accepts or rejects what they’re doing, they are okay either way.

Molly Sheridan

You’ve mentioned an attraction to exploring both “what lies beneath the surface” and “aliveness” through your paintings. How do you find that manifesting?

EJ Hauser

In a way, I think this goes to the question of when a painting is done. For me, it seems like it’s done if the painting has its own energy. It’s broadcasting. You’re trying to get the painting to resonate and be its own thing. When a painting is done, it becomes itself and has the energy of something that’s alive.

Color imbues a painting with aliveness for me. The staccato-like brush mark that is part of my making is another way I feel my paintings get energy. And then composition — how you compose inside the confines of the canvas. Do things vibrate in the middle of the canvas, or is there so much vibration that it goes off the edges? And my subject matter contributes to the aliveness — for me that could be a tree, a mountain, a word, or a frog — all “energetic” things that have appeared in my paintings.

I guess there’s one other way that I think of the energy of art objects, which is the way that a painting can be like a time machine. Let’s think about a Marsden Hartley, for instance, one of my favorite painters. When I step up to a Marsden Hartley painting, I know that I am standing about as far away from the surface as Hartley when he made the piece. I’m standing in what I think of as Marsden Hartley’s space. And the piece I’m looking at pretty much looks like it did when Hartley finished it. Yet the way the painting existed in Hartley’s present is different than the way it exists in my or anyone else’s present. And who can even know how a painting will “function” in the future? But because Hartley is currently part of the canon of important American painters, there will hopefully be a future for his paintings. So in ways like these, paintings can simultaneously contain different layers of past, present, and future, and these temporal complications of painting are not only intriguing but, I believe, proof of art’s aliveness.