Peter Robinson on Building Trust, Black Spaces, and Black Futures in Brooklyn

AAP NYC's fall 2020 studio saw planning and architecture students exchanging ideas about community history, spatial intervention, and social design practices with Brooklyn high school students.

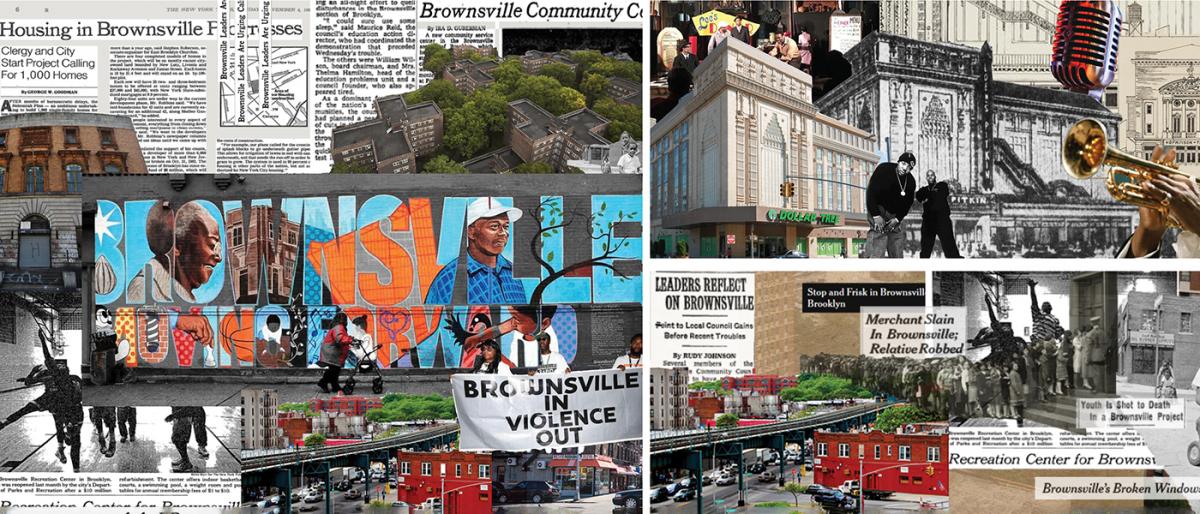

Robinson's fall 2020 AAP NYC studio titled Housing + Sociality, My Brother's Keeper (NYC MBK, an organization founded by President Barack Obama in 2011 for young, Black men) centered around collaborative design research to better understand historical and current issues surrounding Black spaces in Brownsville and other neighborhoods throughout Brooklyn. Progressive stages of research and studies of stories shared by high-school students from Medgar Evers College Preparatory School were leveraged to inform different spatial intervention strategies. image / Savanna Lim

Robinson's fall 2020 AAP NYC studio titled Housing + Sociality, My Brother's Keeper (NYC MBK, an organization founded by President Barack Obama in 2011 for young, Black men) centered around collaborative design research to better understand historical and current issues surrounding Black spaces in Brownsville and other neighborhoods throughout Brooklyn. Progressive stages of research and studies of stories shared by high-school students from Medgar Evers College Preparatory School were leveraged to inform different spatial intervention strategies. image / Savanna Lim

Alumnus Peter Robinson (B.Arch. '98), a New York City–based architect and urban designer brings the values and participatory processes that inform his work on race, architecture, and urban spaces at BlackSpace Urbanist Collective into the AAP NYC studio for a second year. Robinson's students collaborate across disciplines where social planning and architecture intersect and share knowledge across generations to learn from design practices that are shaped by site, community partnerships, and direct experience.

You studied architecture at Cornell AAP and entered the profession in 1998. In 2017, you joined and helped to build the BlackSpace Urbanist Collective. When and how did you decide on architecture for your studies and career? How is your work with the collective central to what you do as an architect and educator?

My interest in architecture and being an architect started at the public high school I attended. I had what I would call uncommon access to important resources that aren't often available to high school students, in particular Black students. Anne Buerger, an AAP alum who studied fine art, taught my architecture studio. She treated us all with respect and introduced me to the practice and studio culture of architecture which prepared me for Cornell. A mentorship program I was part of, as well as an internship I did as a high school student, made me more comfortable applying to Cornell, and, as a young Black man entering a profession where we represent only about 2% of practicing architects, these experiences were invaluable. There is a picture I keep with me and show other people of my friend and me in high school when we first studied architecture, we are both architects today in a profession where there hasn't really been a place for us. I show this picture often and always tell the students to come out and say what it is that they want and things can start to come together, to really happen.

I was at Cornell at a time when a growing number of Black and other minority students had created a network of support. We had MOAPP, or, the Minority Organization of Architecture Art and Planning. Relationships were built there and we maintain that network of support professionally and personally today. Three members of the BlackSpace inaugural board are AAP alums: myself, Ifeoma Ebo (B.Arch. '02), and Emma Osore (B.S. URS '09). We didn't meet at Cornell, and all had different experiences there, but there was a network in New York City so we knew of each other. At BlackSpace, we are a collective of planners, architects, and artists who share common interests and a focus on Black communities, Black experiences, and Black futures — and we all came together pretty organically after two women met at the first Black In Design conference at the GSD in 2015 and decided to continue the conversations that were inspired by the conference. Our first meetings were brunches in each other's homes. After a while, we started hosting brunches with purpose — with topics and activities, no agenda per se, but just really getting to know each other.

We've continued to expand the organization through the network we've grown. Some people who show up to support one event, show up again to support another. Or, for example, Ifeoma and I were at an event in New York City and Sekou Cooke (B.Arch. '99) invited us to put on a workshop for the hip-hop exhibit he was curating at the Center For Architecture. BlackSpace was small and growing and we pulled in people who we knew to support the effort. We knew a planner who was also a DJ, she came on board to support the event. BlackSpace did not have a formal membership structure at that time, we used to say if you're wearing a BlackSpace t-shirt at one of our events then you’re BlackSpace.

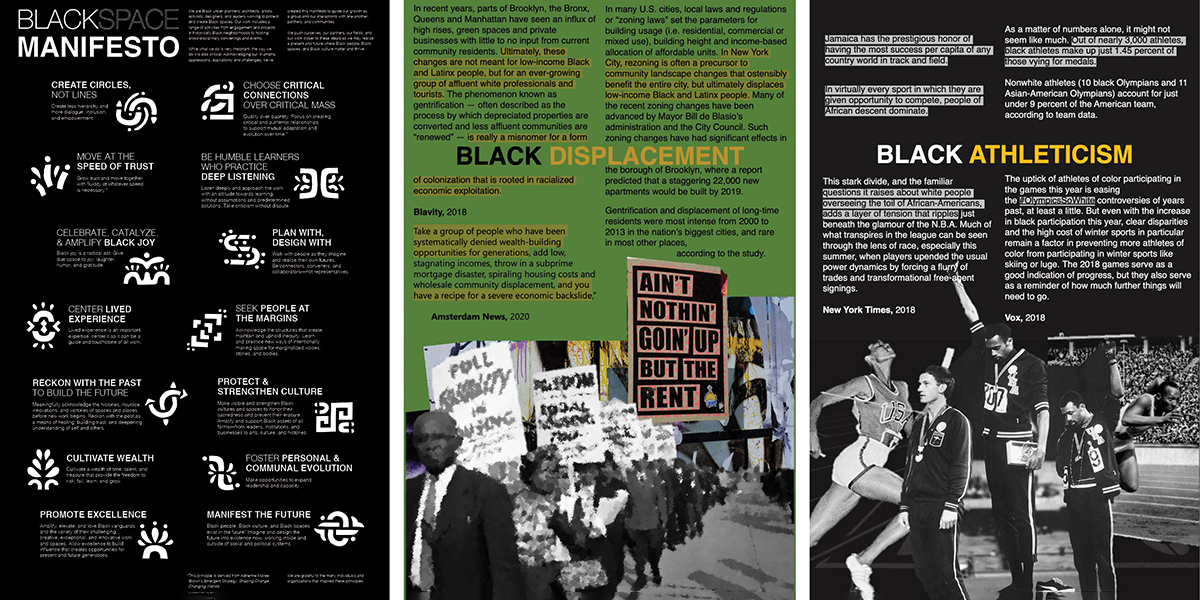

Today, we are guided by our BlackSpace Manifesto. It's a collection of 14 guiding principles that we share on how to work in and with Black communities. These aren't slogans but really meant as starting points for valuable engagement. The manifesto developed organically during our meetings and discussions. In 2017, a core team was assembled to formalize and concretize what was, at the time, an evolving ethos.

Left: BlackSpace created a manifesto built on approaches to participatory research and design that can be shared with the communities, students, and designers the collective brings together for workshops, studios, and other organized events; center, right: collected text and image that AAP architecture and planning students worked with high school students from Medgar Evers College Preparatory school in Brooklyn to bring together in the form of posters demonstrating topics of interest and concern that would inform design processes and direction. image left / BlackSpace Urbanist Collective; center, right / Michael O'Key

Left: BlackSpace created a manifesto built on approaches to participatory research and design that can be shared with the communities, students, and designers the collective brings together for workshops, studios, and other organized events; center, right: collected text and image that AAP architecture and planning students worked with high school students from Medgar Evers College Preparatory school in Brooklyn to bring together in the form of posters demonstrating topics of interest and concern that would inform design processes and direction. image left / BlackSpace Urbanist Collective; center, right / Michael O'Key

Your studio this fall is largely driven by BlackSpace's principles and is, in practice, a collaboration between architecture and planning students at AAP NYC with 14 young, Black men who attend Medgar Evers College Preparatory School (MECP) and participate in the My Brother's Keeper (NYC MBK) program. The central concern of the studio was responding to the following question: "How can we radicalize spatial thinking in such a way that the bodies and consciousness of young Black men are the solution and not the problem in housing?"

Both of these aspects, the collaborative model; and, the question stand out as unique and important. How did the different perspectives, knowledge, and voices in the design studio combine to respond to this prompt?

The studio wasn't as much a formal housing studio as it was a studio about living. It was important that the central focus for work in a Black community, and work in collaboration with young Black men was specifically not a problem. We were not dealing with a problem to solve with design. In part, because young Black men were present in the studio, we were reminded that we're dealing with people rather than a design problem to be solved. The humanity in that allowed for specificity, difference, and different ways of articulating knowledge and experience, which meant everyone had something to learn from each other. As an instructor, I needed to step back and let our ideas change about design and what architecture could be as determined by what these 14 young Black men shared in conversation with the Cornell students they were collaborating with.

Sometimes we ended up with confusion over how to proceed when initial questions were answered in unexpected ways, and conversations took a different turn. Simple questions such as, "What does home mean to you?" resulted in working with a Nigerian Evangelical church that was more interested in their congregation than in their building, or another student on what a catering kitchen for him and his mother to prepare traditional Jamaican food would look like, and how to make that happen. Another group designed a hoodie that would help a young Black man to walk safely around his neighborhood.

It helps that initially, the Cornell students began by working with the Brownsville Heritage House, an organization that has offered our studio tremendous support. Executive Director Mariam Robertson's local and lived knowledge of her community provided the grounding of how knowledge would be built in the studio. She is responsible for an archive of objects and curios that reflect the history and lives of Black people in Brownsville and Brooklyn.

Design and ideas about design evolved in a number of ways that were literally a reflection of the conversations the groups were having from the beginning and throughout the process — this fluidity has been critical for everyone involved.

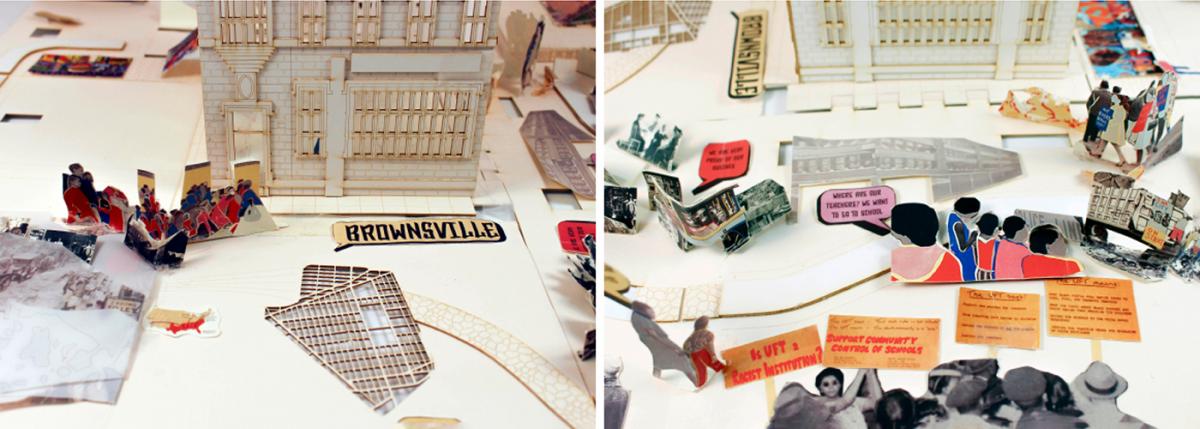

Studio groups made up of students from different disciplines, backgrounds, and generations shared skills and stories to better understand relationships between domestic and urban spaces—and, how design approaches can revolve around the experiences and specific interests of neighborhood residents, in this case, young, Black high school–aged men. From left: a study of community and spatial relationships that coexist at the Glory of God Christian Center, a space that one high school student thinks of as home; a study of the interior/exterior spaces surrounding another student's experience of daily domestic life; a study of the different spaces that make up a building's levels and possibilities for developing them into spaces that better support the different functions of a student's home life. images / Jeniffer Carmona

Studio groups made up of students from different disciplines, backgrounds, and generations shared skills and stories to better understand relationships between domestic and urban spaces—and, how design approaches can revolve around the experiences and specific interests of neighborhood residents, in this case, young, Black high school–aged men. From left: a study of community and spatial relationships that coexist at the Glory of God Christian Center, a space that one high school student thinks of as home; a study of the interior/exterior spaces surrounding another student's experience of daily domestic life; a study of the different spaces that make up a building's levels and possibilities for developing them into spaces that better support the different functions of a student's home life. images / Jeniffer Carmona

You made clear from the start of your studio that groups would not only respond to a design brief, they would also "build relationships, leverage resources, share information, and co-create intervention strategies that celebrate and amplify the lives of young Black men in domestic space." Can you share thoughts on how this model provides a productive context for working with Black communities in the studio at AAP NYC, a space for both teaching and learning design?

The studio is the result of preexisting relationships that we invest in over time. With the Brownsville Heritage House. or, for example, with Quardean Lewis-Allen, executive director of the Youth Design Center (previously Made in Brownsville) and a BlackSpace member. The AAP NYC 2019 studio was chiefly a collaboration with Quardean's organization and the Brownsville community. I had the opportunity to expand this way of working with NYC MBK and the organization's executive director George Patterson. Quardean had hosted a STEM workshop at Meyer Leven School in Brooklyn where George was the principal, and so George was invited to reviews at last fall's studio which were held at the Brownsville Community Justice Center. This year, George was very receptive to the idea of involving NYC MBK in the studio. He knew that Quardean was an alum at MECP and that that school had successfully matriculated 20 students in the engineering program at Cornell. So there were actually sets of existing relationships to be invested in. We also had a very corporative partner in Principal Wiltshire at MECP and I could not have pulled this studio off without his already embedded support network.

Generally, I sought to build equity in the studio. We had 14 Cornell students so we had 14 young men from the Medgar MBK program. They began by working in teams of 8 or 6 and then broke off into one-on-one engagement. The individuality that shaped each project definitely makes the whole studio stand out as an investigation of process as much as it is about producing form. This was something that was at times a challenge for students to accept or embrace, but ultimately the collaborative aspect was compelling for many, including the vice-chancellor for the board of regents, and Dr. Wilshire who participated in our mid-term review where collaboration foregrounded the display of work and drove the conversation.

One group created a video that collected images of places of particular importance for daily life in Brooklyn, combined and aggregated them with images of places tied to family history, and mapped them around a central node, a student's home in Prospect Park. video / Aybuke Altug

One group created a video that collected images of places of particular importance for daily life in Brooklyn, combined and aggregated them with images of places tied to family history, and mapped them around a central node, a student's home in Prospect Park. video / Aybuke Altug

What do you see as important outcomes of design studios and practices that have a heavy emphasis on process — or, not only on what you do, but how you do it?

In our case, the way we were working — with many partners generously giving their time and other resources — and, with the fluidity necessary for a genuinely collaborative process that gives each person an opportunity to bring what they have to the group as they build trust as well as working relationships that shape a project, there are several outcomes that I'm excited about. The projects have a distinct value in the sense that they redefine roles and shift relationship dynamics among and between community members and designers. The studio also provided both learning opportunities for the college students and mentorship opportunities to the high school students who are thinking about the application process. And people noticed. The Medgar Evers students will receive academic credit for their work. The high school has been invited to apply for a $250,000, three-year renewable, grant for educational programming that shares the model of this studio with another school in Brooklyn.

I've never seen projects like these come out of a studio — they are unique, creative, well-thought-out, and largely practical. The generosity from my colleagues who created opportunities for engagement for the students and attended reviews giving of their thoughts and time, as well as from community leaders who have been involved, attentive, and inspired to find resources that support this model of design education, has been incredibly exciting for me.

Peter Robinson's fall 2020 studio was his second at AAP NYC. This iteration involved people, organizations, and opportunities that made it possible. In addition to those mentioned above, Robinson also thanks: Alicia Ajayi, Erica Cochran Hameen, Najeeb Hameen, Olalekan Jeyifous (B.Arch. '00), Justin Moore, Eloy Ortega, Anaelechi Owunwanne, Justin Richardson, Iris Robertson, Scott Ruff, Andrew Thompson, Cornelius Tulloch (B.Arch. '21), Ife Vanable, Michele Washington, Nathan Williams, and Cathie Wright-Lewis.