Guorun Yang: Linqing Tribute Bricks – Kiln Fires, Canal Memories

Translation Below:

临清贡砖:窑火映照的运河记忆

临清贡砖是一种古老的手工建筑材料,也是北京皇家建筑的特供用砖。北京皇家建筑的辉煌离不开临清贡砖的崛起。故宫、明十三陵、北京城墙、天坛等著名建筑都使用了临清贡砖建造。临清贡砖的生产从明初延续至清末,跨越了五百年的历史。

永乐初年,明成祖朱棣将政治中心迁至北京,并开始修建宫殿、城墙、陵墓等建筑,向全国征调大量砖块。明清时期,朝廷对贡砖的需求量巨大,每年高达百万块。《临清志》记载:“明永乐间设分司,初侍郎或郎中,后以主事督征之……岁额城砖百万。”砖款由国家拨发给窑户,并接受官府检查和管理。

临清贡砖在全国众多皇家砖窑中脱颖而出并非偶然,它的兴盛与临清的发展都得益于京杭大运河会通河段的畅通。会通河的修建将临清至于南北水路通行的必经站点,向南是江淮运河,向北则是天然运河卫河。卫河常年水源充足,为贡砖生产提供了稳定的运输渠道。临清也从四千人的农耕村庄发展成了六万人口的运河都市。

临清地处黄河下游冲积平原,卫河正是黄河改道形成的天然河流。黄河泛滥带来的黄土高原黄沙土与本地红黏土结合,形成了独特的“莲花土”。这种土壤细腻无杂质,沙粘适中,烧制的贡砖质地坚硬,“敲之有声,断之无孔,坚硬茁实,不碱不蚀”,是其特性的最佳描述。

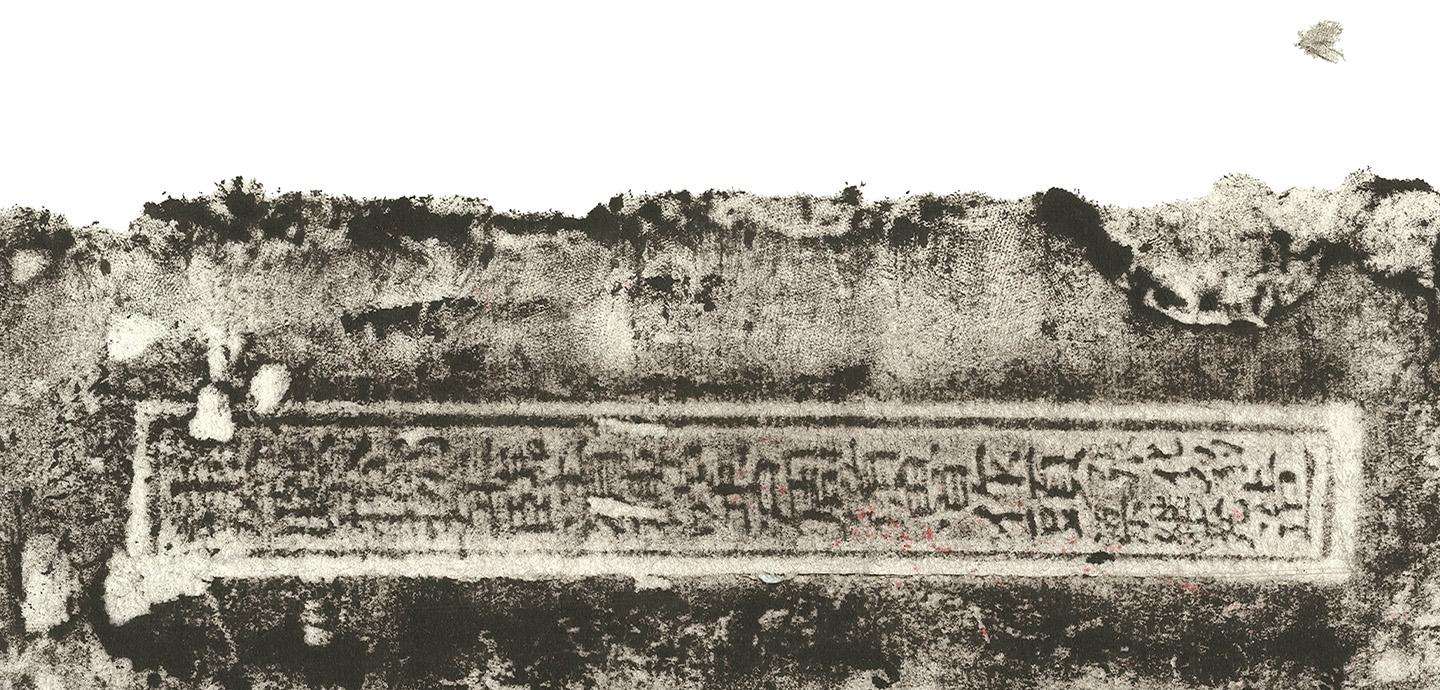

临清贡砖的生产工艺极为复杂,且有严格的质量监管。一块砖的制作需经历十多道工序,每道工序都包含多种技巧。本次展览展示了其中的七个关键步骤:制坯、晾坯、验坯、装窑、焙烧、洇窑、出窑。与其他手工砖不同的是,古代贡砖上印有生产年份、生产组织者及窑厂主的名字。这种独特标记是一种责任机制的体现,质量不过关的砖可以直接追溯到制作者的名下,使其承担责任。

然而,随着时代的发展和古代城市建筑的衰落,临清贡砖逐渐退出了历史舞台。曾经的辉煌如今只能通过文字记载和口述历史来追溯。如今,仅有少数窑厂仍在坚持贡砖的制作,他们保留了传统的工艺流程和制作技艺,使这一古老技艺得以延续,并被列入非物质文化遗产名录。

现在,临清的农田旁、运河岸边,依稀可见连绵起伏的土堆,这些便是明清时期遍布运河两岸的贡砖官窑遗址。当年,这里的官窑规模曾高达数百座,成为当时全国最大的制砖工程。附近的村庄也因古窑而得名,如东窑、西窑、白塔窑等,见证了那段辉煌的历史。

临清贡砖的故事是大运河的故事,也是大地与火的记忆,它承载的不仅是对一个时代的回忆,更是对当今科技、劳动力、土地、运河与城市之间关系的反思。

特别致谢:

临清贡砖制作技艺传承人赵庆安

临清刘英顺工作室

临清市文化馆

临清市博物馆

Zeuler R. Lima

Florian Idenburg

Erin Pellegrino

展览策划,设计:

杨国闰

布展:

杨国润

Trang Nguyen

Olaoluwa Adebayo

王梓帆

Linqing Tribute Bricks: Kiln Fires, Canal Memories

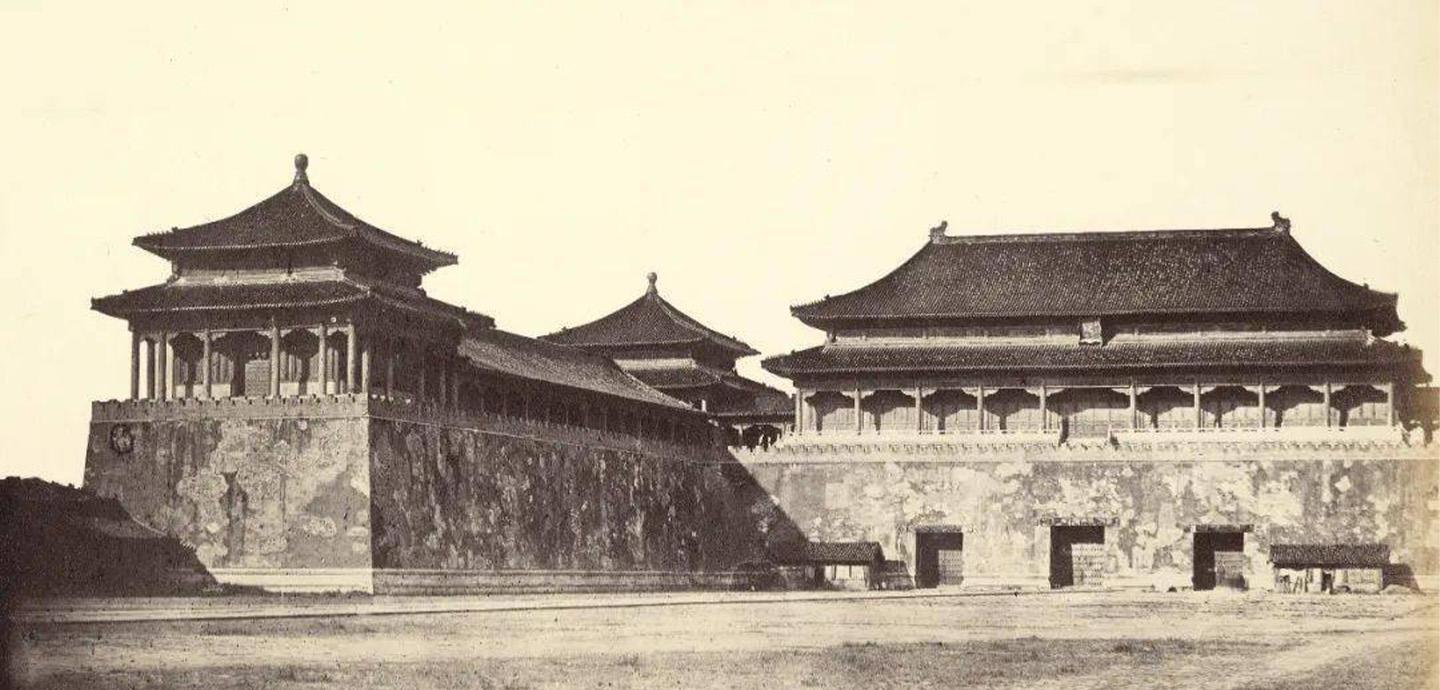

Linqing tribute bricks are an ancient handmade building material specifically produced for the construction of Beijing's imperial architecture. The grandeur of Beijing's imperial buildings is inseparable from the rise of Linqing tribute bricks. Iconic structures such as the Forbidden City, the Ming Tombs, the Beijing city walls, and the Temple of Heaven were all built using Linqing tribute bricks. The production of these bricks spanned from the early Ming Dynasty to the late Qing Dynasty, covering a history of over five hundred years.

In the early years of the Yongle reign, Emperor Zhu Di moved the political center to Beijing and began constructing palaces, city walls, and mausoleums, leading to a nationwide demand for bricks. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the imperial court's demand for tribute bricks was enormous, reaching up to a million bricks annually. According to the Linqing Chronicles, "During the Yongle period, a supervisory office was established, initially overseen by senior officials or secretaries, later by directors…The annual quota for city bricks was one million." Funds for brick production were allocated by the state to kiln owners, with strict government inspection and management.

The prominence of Linqing tribute bricks among the numerous royal kilns across the country was no accident. Its prosperity, along with the development of Linqing itself, was greatly facilitated by the opening of the Huitong River section of the Grand Canal. The construction of the Huitong River positioned Linqing as a crucial hub for north-south water transport: to the south, it connected to the Jianghuai Canal, and to the north, it linked to the natural Wei River. The Wei River, with its abundant water supply year-round, provided a stable transportation route for the tribute bricks. As a result, Linqing transformed from a small agricultural village of four thousand people into a bustling canal city with a population of sixty thousand.

Located on the alluvial plain of the lower Yellow River, Linqing benefited from the Wei River, a natural waterway formed by the Yellow River's course changes. The flooding of the Yellow River brought loess from the Loess Plateau, which, over time, mixed with local red clay to form a unique soil known as "lotus clay." This clay, fine and free of impurities with an ideal balance of sand and clay, produced bricks of exceptional quality. Described as "resonant when struck, solid when broken, hard and durable, resistant to alkali and erosion," these bricks were unparalleled in their properties.

The production process of Linqing tribute bricks was highly complex and subject to strict quality control. The creation of a single brick involved over ten meticulous steps, each requiring specialized skills. This exhibition highlights seven key stages: molding, drying, inspection, kiln loading, firing, diffusion, and unloading. Unlike other handmade bricks, ancient tribute bricks were stamped with the production year, the name of the supervising official, and the kiln owner. This unique marking system served as an accountability mechanism, ensuring that any substandard bricks could be traced back to their makers.

However, with the passage of time and the decline of traditional architecture, Linqing tribute bricks gradually faded from prominence. The glory of their past can now only be glimpsed through historical records and oral accounts. Today, only a few kilns continue to produce these bricks, preserving traditional techniques and craftsmanship. This enduring art form has been recognized as part of China's intangible cultural heritage.

Nowadays, along the farmlands and canal banks of Linqing, one can still see the faint outlines of earthen mounds—remnants of the once-thriving tribute brick kilns that lined the canal during the Ming and Qing dynasties. At their peak, these kilns numbered in the hundreds, forming the largest brick-making operation of their time. Nearby villages, such as Dongyao, Xiyao, and Baitayao, were named after these kilns, bearing witness to this illustrious history.

The story of Linqing tribute bricks is a part of the story of the Grand Canal; it bears memories from the earth and fire. It not only evokes nostalgia for a bygone era but also invites reflection on the intricate relationships between technology, labor, land, waterways, and cities in the modern world.

Special Acknowledgments:

Zhao Qing'an, Inheritor of the Linqing Tribute Brick Craftsmanship

Liu Yingshun Studio, Linqing

Linqing Cultural Center

Linqing Museum

Zeuler R. Lima

Florian Idenburg

Erin Pellegrino

Exhibition Curation and Design:

Guorun Yang (M.Arch. '25)

Exhibition Installation:

Guorun Yang (M.Arch. '25)

Trang Nguyen (B.Arch. '25)

Olaoluwa Adebayo (M.Arch. '25)

Zifan Wang (M.Arch. '25)