Best Designed By Doing: Radical Hybrid Thinking Across Disciplines

In 2019, as part of the new pilot collaboration between the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP) and Cornell Tech, colleagues came together across disciplines to explore innovative ways of teaching and thinking about design and technology. Three years later, having gained a wealth of experience to reflect upon and celebrate, they are poised to take their ideas even further.

The complexity of the world around us demands equally sophisticated ways of designing and building for this environment. Yet, considering the rapid pace of progress in individual fields of research and the challenges of working beyond them due to differences in language and practice, making space for collaboration across diverse disciplines can be lost if not approached with intention. It was with this goal firmly in hand that the pilot studio between the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning (AAP) and Cornell Tech was created to focus on intersections of design and technology in 2019. Three years later, Associate Professor Jenny Sabin, architecture; Associate Professor Wendy Ju, information science; and Professor Uli Wiesner, materials science and engineering, consider the impact of the pilot on both faculty and students; explore lessons in pedagogy, research, and hybrid thinking; and reflect upon the benefits and practical challenges of cross-college collaboration.

1

Can you start by explaining what inspired the creation of the pilot program, and what initially brought you together?

Jenny Sabin: The studio was launched as part of the new pilot collaboration between AAP and Cornell Tech. Since the fall of 2019, incoming M.S. Matter Design Computation (MDC) students have spent their first semester in residence at Cornell Tech. Together with Cornell Tech students across their various programs, we have piloted Design & Making Across Disciplines, Coding for Design, and modules related to Design for Physical Interaction. As part of a university-wide initiative, Wendy Ju and I are also cochairing a faculty task force working on the charge put forth on education and research at Cornell in areas related to design and technology. One part of this charge includes identifying opportunities for new undergraduate and graduate design courses and degrees, and developing a possible structure and road map for such an entity. The pilot studio is testing just that. In Design & Making Across Disciplines by colleagues, information science (Wendy Ju), biomedical engineering (Jonathan Butcher and Nate Cira), materials science and engineering (MSE) (Uli Wiesner and Marty Murtagh), and myself students are introduced to radical hybrid thinking in design and technology across disciplines.

Wendy Guang-wen Ju: We felt that our idea of bringing multidisciplinary and research-oriented input together and integrating it into the design process was best prototyped by doing it. One of the most exciting aspects of exploring the intersection of our disciplines in an education and studio setting is that we are really getting a chance to see how students we have introduced to all of our work synthesize these ideas into something new.

2

How has this collaborative experience intersected with your personal expertise and research interests?

JS: Rooted in more than 17 years of transdisciplinary collaboration, my research, projects, and teaching investigate the intersections of architecture and science, applying insights and theories from biology and mathematics to the design of responsive material structures and ecological spatial interventions for diverse audiences. Although there have been tremendous innovations in design, material sciences, and bio- and information technologies, direct interactions and collaborations between scientists and architects are still rare. A difficult part of this collaborative work is figuring out how to structure transdisciplinary opportunities for students and faculty. This pilot studio has allowed us to test new possible pedagogical structures through teaching modules and, importantly, introduce complex concepts through accessible means and methods. I've learned a lot from my colleagues in the process, especially in thinking about our diverse definitions of design and technology. It does not have a singular definition and it is not owned by a singular field. Design is everywhere, especially at Cornell!

WGJ: I've been challenged by this course, in a good way, by thinking about design at different scales. Interaction design primarily happens at a human scale, and I tend to design interaction with objects that are limited in range from the size of a watch to the size of a car. Working with my co-instructors through our students, I really started to think about how interaction happens at different physical and temporal scales.

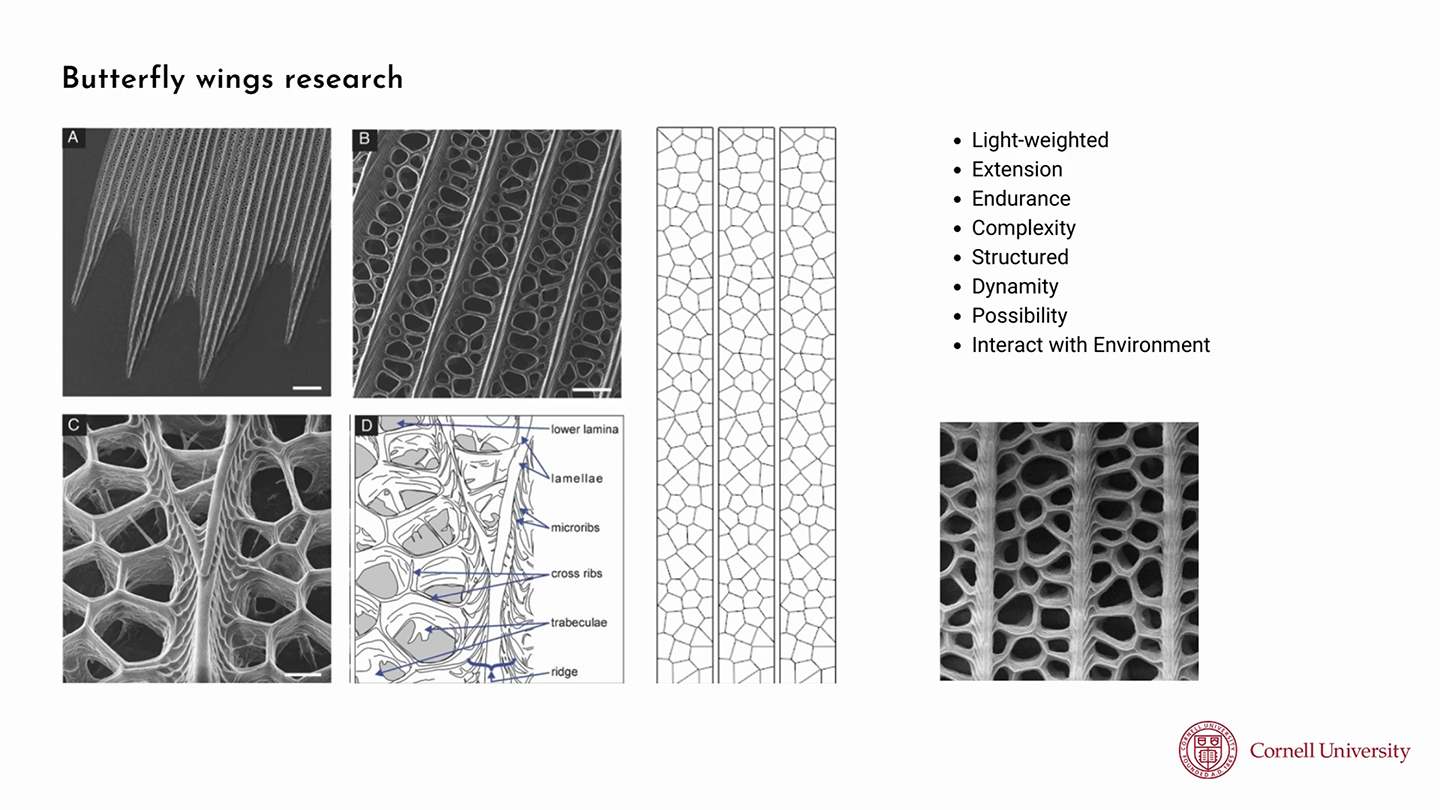

Uli Wiesner: I learned of this course through the university's Radical Collaboration task force on Design + Technology that Jenny mentioned and that I am a member of. I am a physical chemist by training and have been on the faculty in MSE at Cornell for over 20 years. My interests are centered around nanostructured materials and range from nanoparticles for applications in oncology (Cornell dots), across polymer membranes for water filtration, nanomaterials for energy and sustainability applications, and all the way to polymer self-assembly-derived quantum materials. For the sesquicentennial celebrations of Cornell in 2015, my group worked with the American-Korean artist Kimsooja and folks in AAP to generate what Kimsooja referred to as the Needle Woman, a more than 40'-tall structure on Cornell's Arts Quadrangle. For this structure, we generated over 260 transparent panels coated with a ten-micron thick nanostructured polymer film that showed beautiful iridescent colors like those of the morpho butterfly, which changed depending on the time of day and incident angle of sunlight hitting the structure. For my students and me, this was a transformational experience. It was the first time we had engaged in a truly "radical collaboration" across multiple divides, including across multiple colleges as well as across vastly separate length scales (from nanometers to meters). It changed my thinking about different disciplines, the arts and the sciences, and how we can work together. When I heard from Jenny and Wendy that they were teaching this transdisciplinary course and were looking for faculty to chip in, I got very excited and immediately signed up for it. At the graduate level in particular, I think teaching such radically interdisciplinary courses is of enormous importance, as today's problems are highly complex and require individuals with vastly different research backgrounds to effectively communicate and work together. This program definitively prepares students well for this challenge.

3

What did you find to be the most interesting or impactful teaching moments, lines of inquiry, or resulting projects during the pilot?

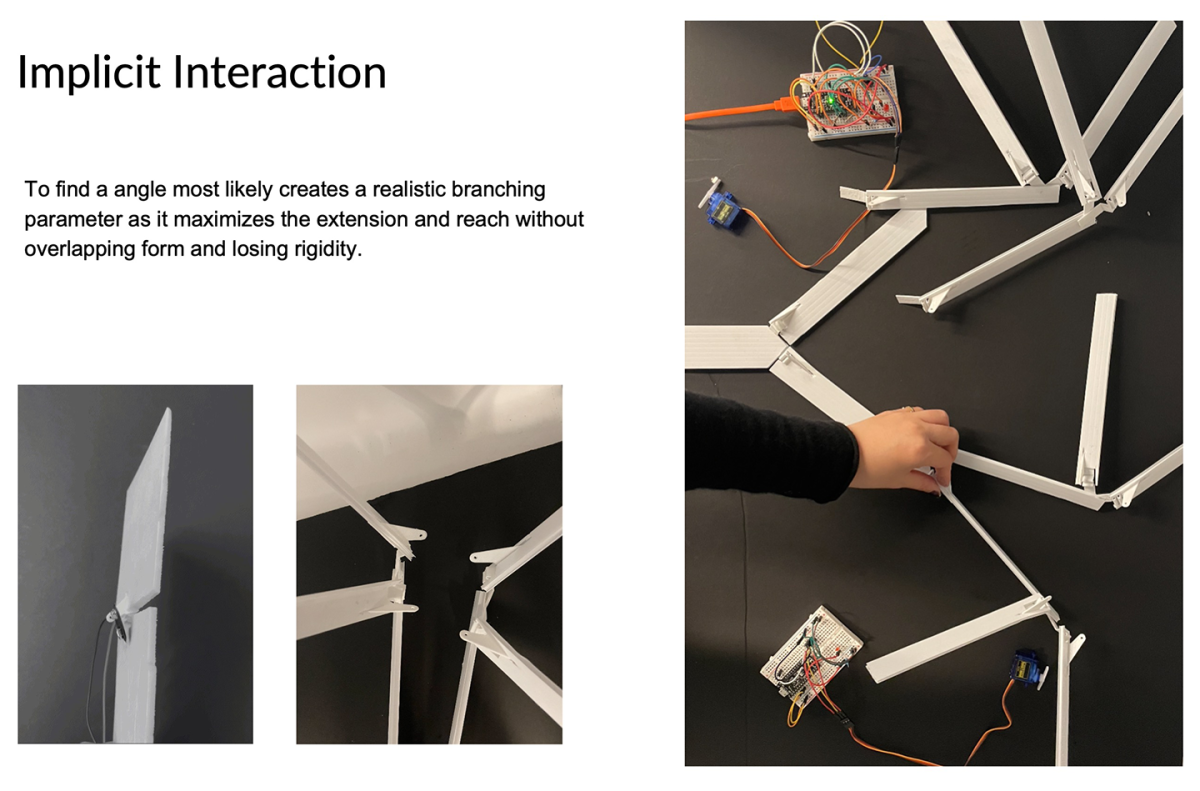

WGJ: I noted that in the final projects the students applied the instruments I taught to manipulate physical shapes or characteristics in their physical structures or form prototypes, and the sensors were usually used to respond to time or external events rather than human behaviors. I'm interested in both broadening the library of physical transformations we explore and deepening our discussion of sensing and material use.

UW: I had never participated in a course with a studio component. In MSE, we have lab components in our courses, but we don't have a studio element in our curriculum. To see the creativity of the students in combining elements of design, materials, biology, interactions, computation, and architecture that they had learned about in the various modules taught in this course literally blew me away. It is very challenging to "teach" creativity. What I have seen students make and do in this program has been the closest thing to it that I have experienced so far. The excellent infrastructure at Cornell Tech with various tools, including various 3D printers, allows the students to take their design ideas and transform them into physical models. Together with computational approaches, they can use inspiration from these models to generate structures on architectural-length scales. When one of the members of the final evaluation panel said, "I wish I would have had such a course during my time as a student," that comprehensively summed it up for me.

JS: We have had to stay nimble in our teaching to cater to so many diverse backgrounds and ranges of expertise. This influences everything from lectures to workshops to critiques. Thankfully, the Product Studio curriculum, a staple and required course for all students at Cornell Tech, introduces a methodology that is very much based on how we design. This provides an important bridge.

The success of the four-year pilot program with Cornell Tech and the M.S. MDC program demonstrates that we are educating a broad group of design leaders. Last year, all of the student groups developed a responsive demonstrator pavilion sited on the Cornell Tech campus. Their proposals were based on the processes, methods, and thinking developed in the modules that structure the first half of the semester. This year, we are going to let the applied design projects emerge through the students' process, which could range from a digital tool, a wearable, a responsive interface, or a building skin. I'm excited to see what emerges over the course of the semester.

4

Remarkably, the pilot program crosses three colleges and two cities. Why do we need this kind of transdisciplinary educational opportunity? What new ways of thinking and working does it open up, both for you and your students?

UW: This pilot crossing three colleges and two cities is a microcosm of what today's complex problems and their possible solutions look like. Issues like climate change, pandemics, energy crises, and water shortages are delocalized in nature, and require highly interdisciplinary approaches and modes of thinking that cross all kinds of boundaries, length, and time scales. We literally have to get out of our own "boxes" and engage in transdisciplinary conversations and actions. And by the way, through the COVID-19 pandemic, the current generation of students is already used to such "delocalized" interactions and actions. The other core element that I think the course handles well is finding the right balance between theory and practice. The progression of teaching modules introduces students to creative approaches and solutions used in very different disciplines. During the studio component, they use what they learn from other components and directly translate that into novel designs, physical and computer models, 3D-printed structures, and architectural designs. The course thus provides them with an unusual set of helpful tools that prepares them well for complex challenges in their future careers. It literally trains them to become the thought leaders of tomorrow.

JS: Recent advances in computation, visualization, material intelligence, and fabrication technologies have begun to alter fundamentally how we design, construct, and make across disciplinary boundaries. These new intersections between the digital, physical, and biological are radically altering the world from the nano to the macro scales. New models are needed for design research, alternative forms of practice, design pedagogy, and collaboration across disciplines, industries, and practice. One approach entails the hybridization of labs and studios to fuse innovations across science, engineering, and design to generate next-generation materials and structures that are adaptive, efficient, smart, and resilient.

5

Where has this work led, both in terms of your own practice as well as future course offerings? What's next?

JS: In my own work, the pilot has opened up new opportunities for research collaborations with my colleagues. For example, Jonathan Butcher and I are part of a new project recently funded by the National Science Foundation, Convergence of Biology and Architecture: How Emergent System Dynamics Generate Adaptable, Robust, and Resilient Forms. Together with PI Adrienne Roeder, we will be working with colleagues at Cornell, Tuskegee University, and the University of Minnesota. In terms of new programs, Coding for Design I & II have been taught in the fall and spring semesters since 2019 and have been required courses for our M.S. MDC students. Through this pilot, we have successfully tested and demonstrated the relevance of these course changes and collaborations between students and faculty with diverse disciplinary backgrounds in design, emerging technologies, engineering, and the sciences. There's much more to come.

UW: Bringing bright and very diverse folks together is always fun, and usually leads to unexpected results and creative new approaches. In particular, this course has started to provide an unusually stimulating intellectual environment that will increasingly draw the most creative and talented students to Cornell. From my personal perspective, that is one of the most important outcomes — attracting the brightest, most creative students in order to address and solve the most pressing and complex problems of our times. It will be really fun and exciting to see this initiative develop further in the future.

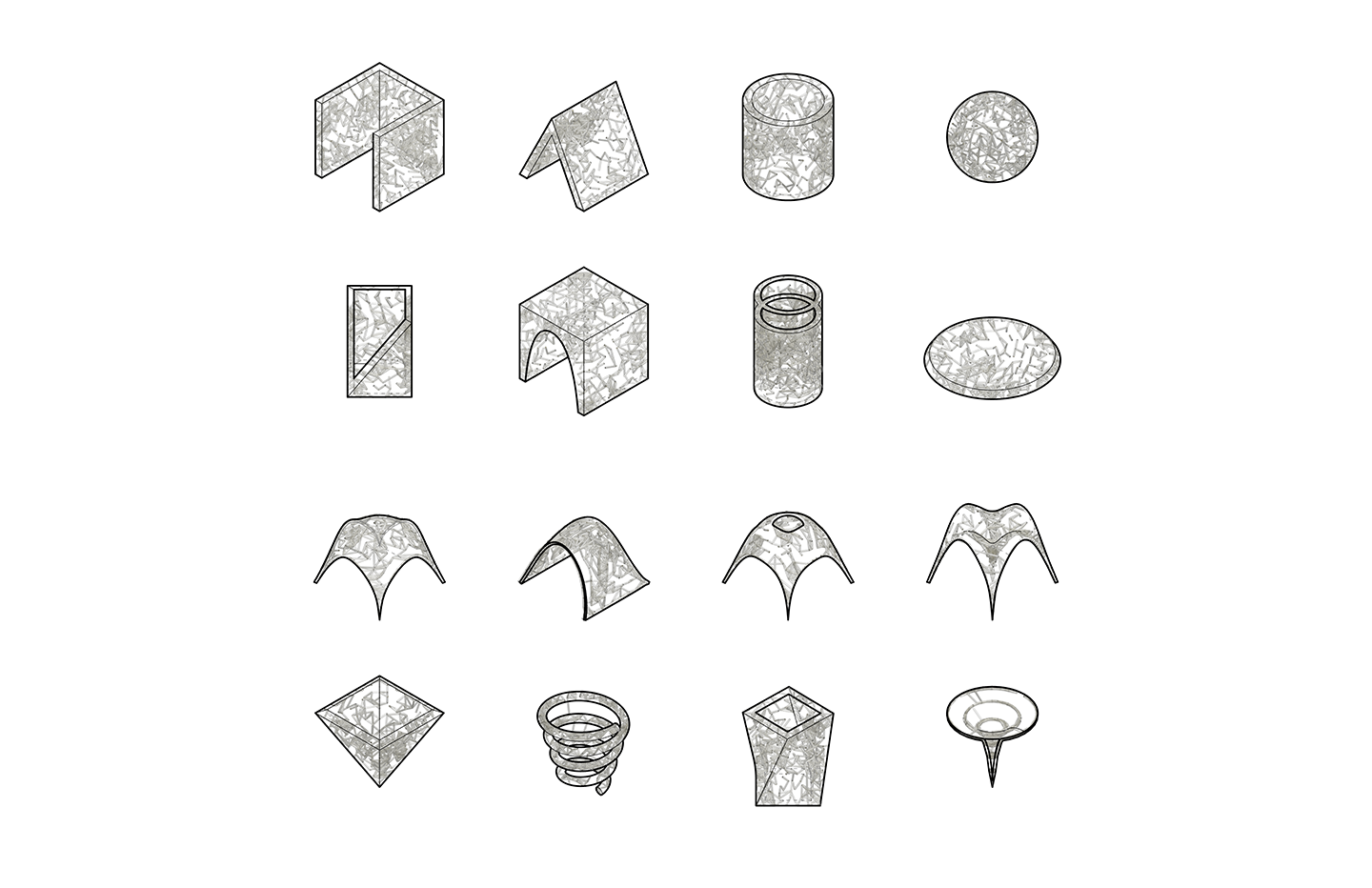

In early modules, students were tasked with investigating natural structures through drawing and procedural notation and using those generated patterns and structures as a basis for creating parameterized cut and fold patterns using digital fabrication methods. image / Yehong Mi, Shuo Feng, and Sylvia Ding

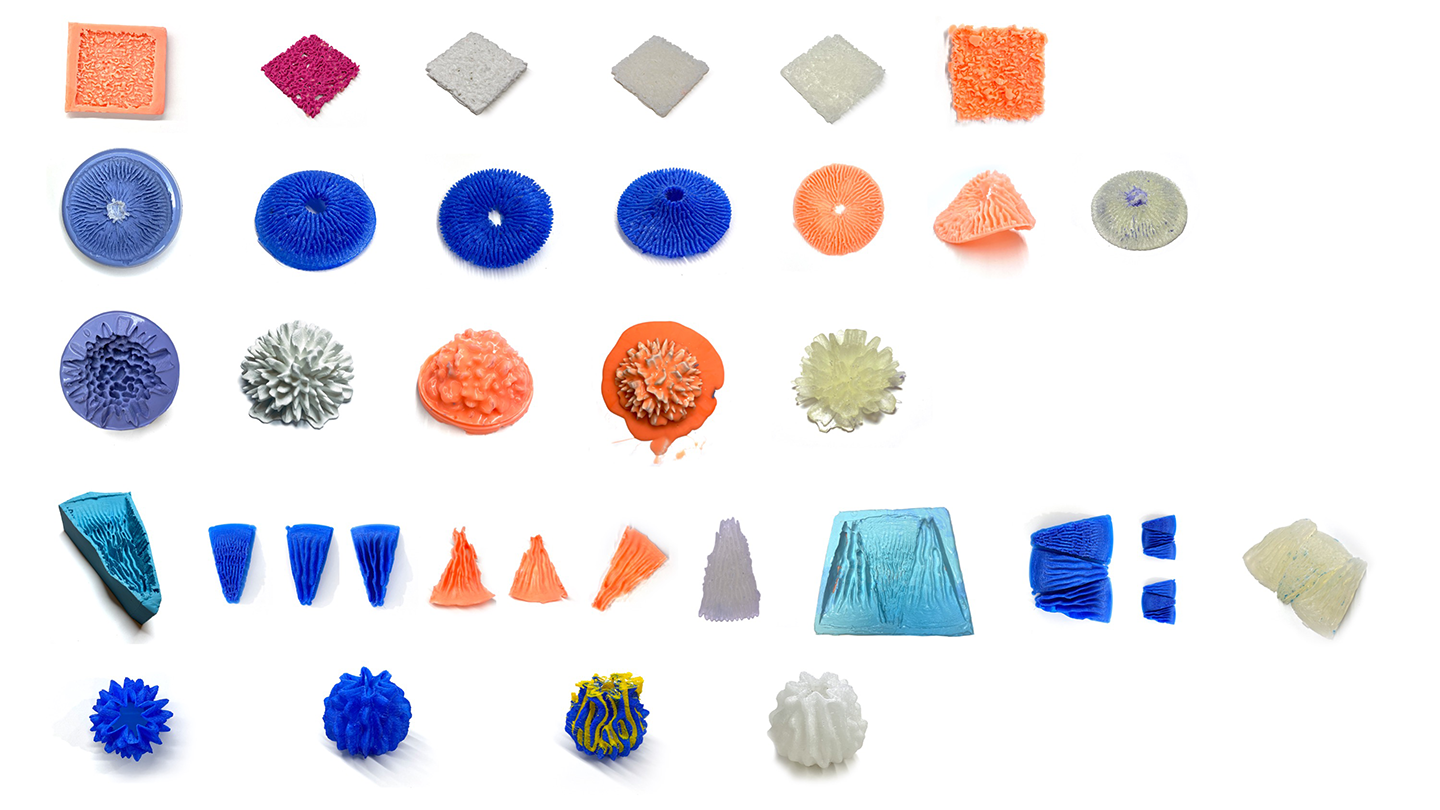

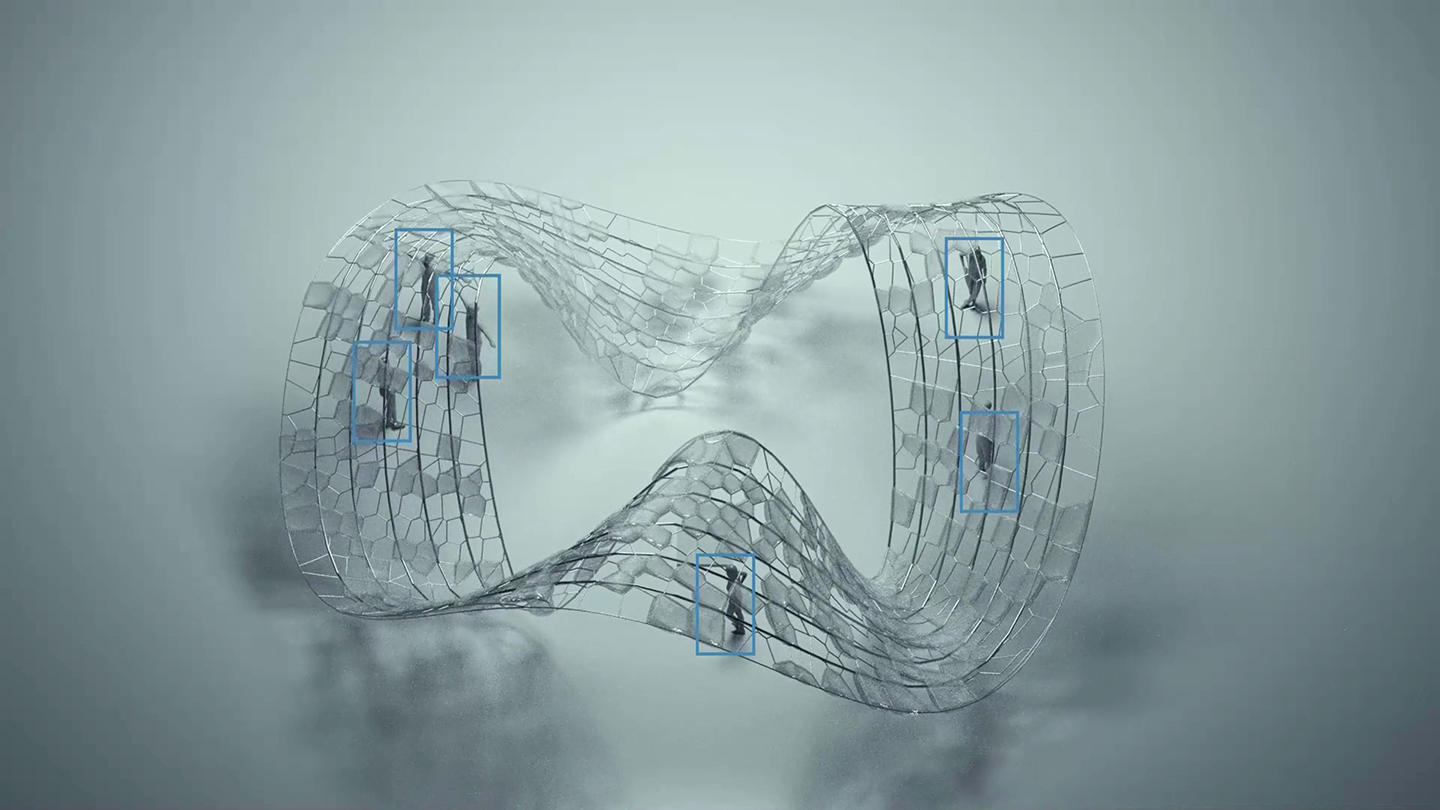

In later modules, students were tasked with further developing the systems and methodologies investigated in the first modules by integrating responsive material constraints and human interaction. This resulted in 3D objects fabricated through 3D printing and other casting techniques. image / provided

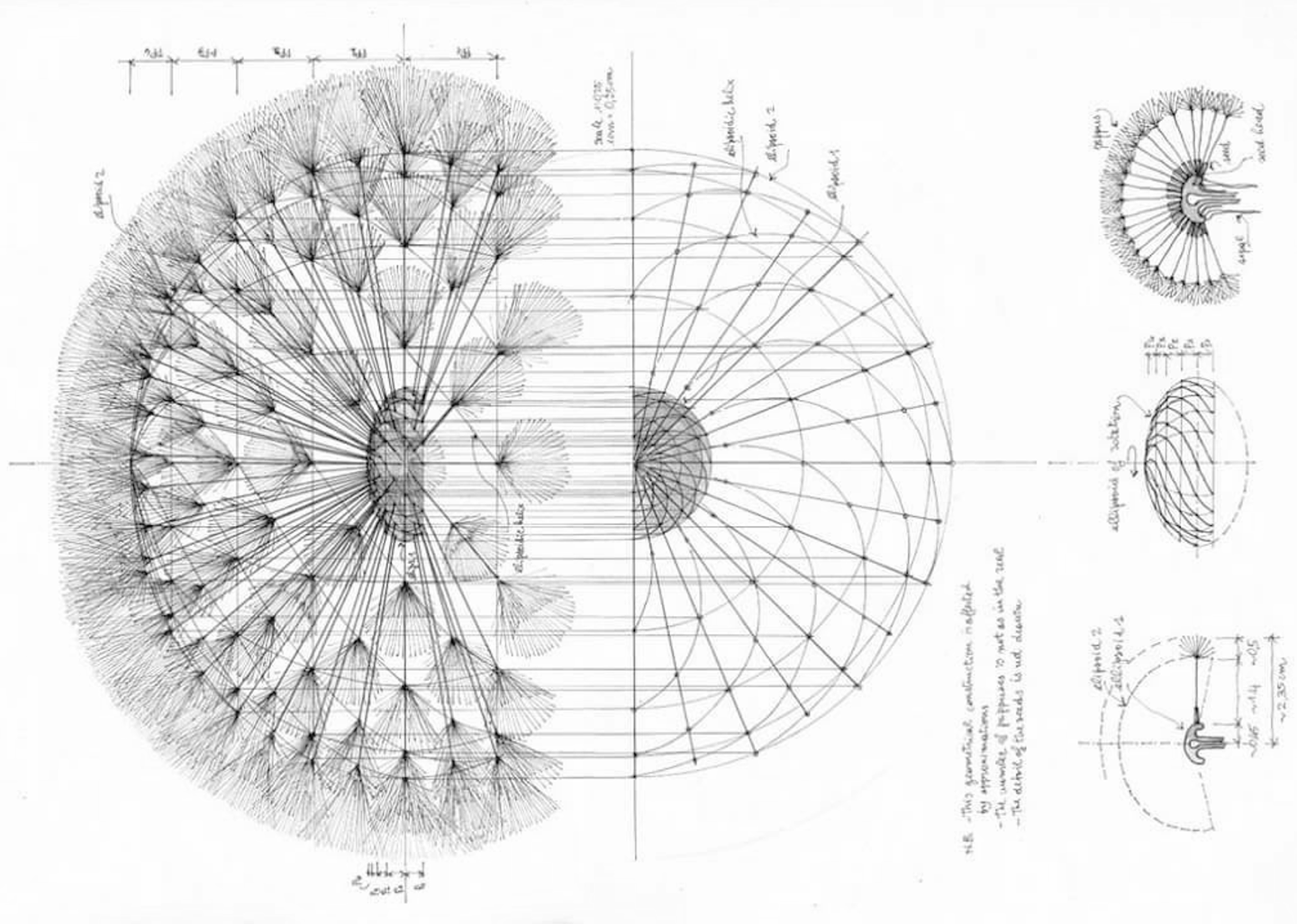

Notation drawings of the spiral configurations of Dandelion flowers. Their spiral formations are the result of branching systems and serve as a source for investigating responsive and adaptive architectural assemblies later in the semester. image / Yangli Hu, Daniel Min, and Renzhi Hu

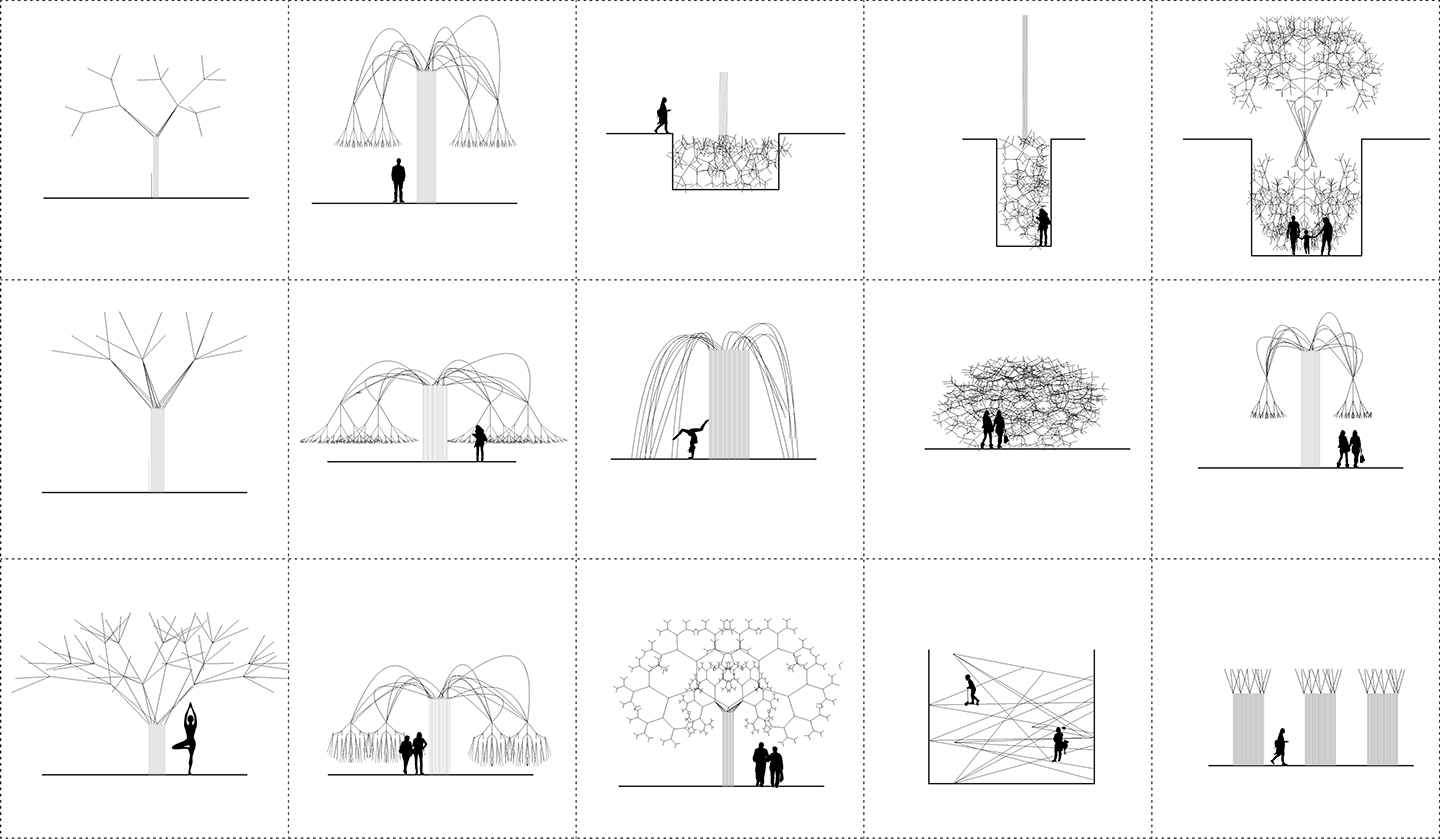

A matrix drawing of the many different conceived configurations of experiential moments inside the Weeping Pavilion. The pavilion was developed as an investigation of branching structures and their ability to variegate space and generate informal programs. image / Yangli Hu, Daniel Min, and Renzhi Hu

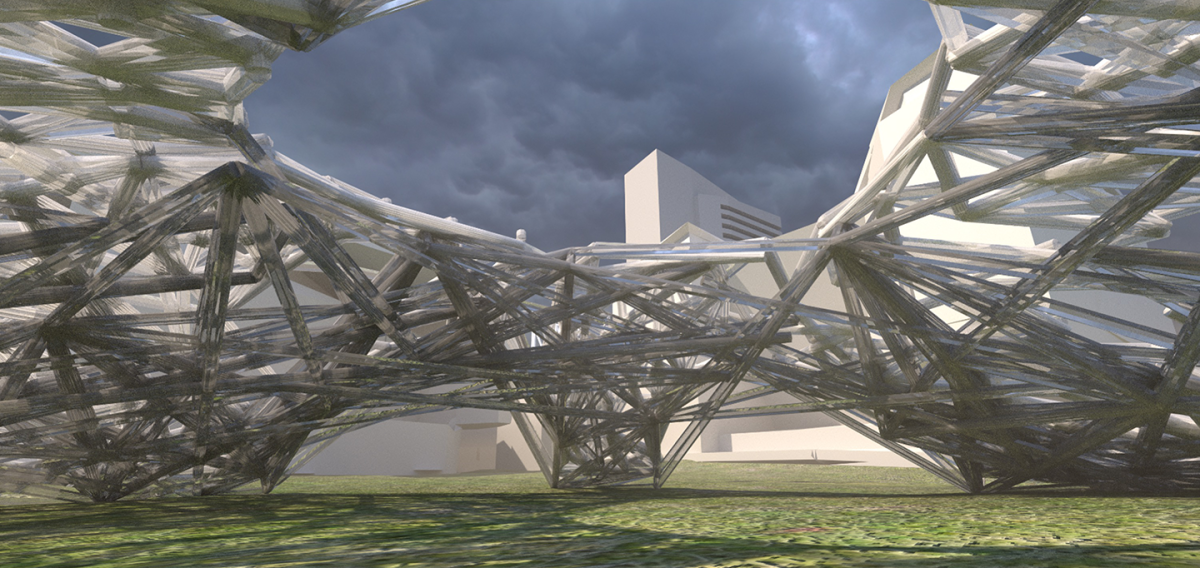

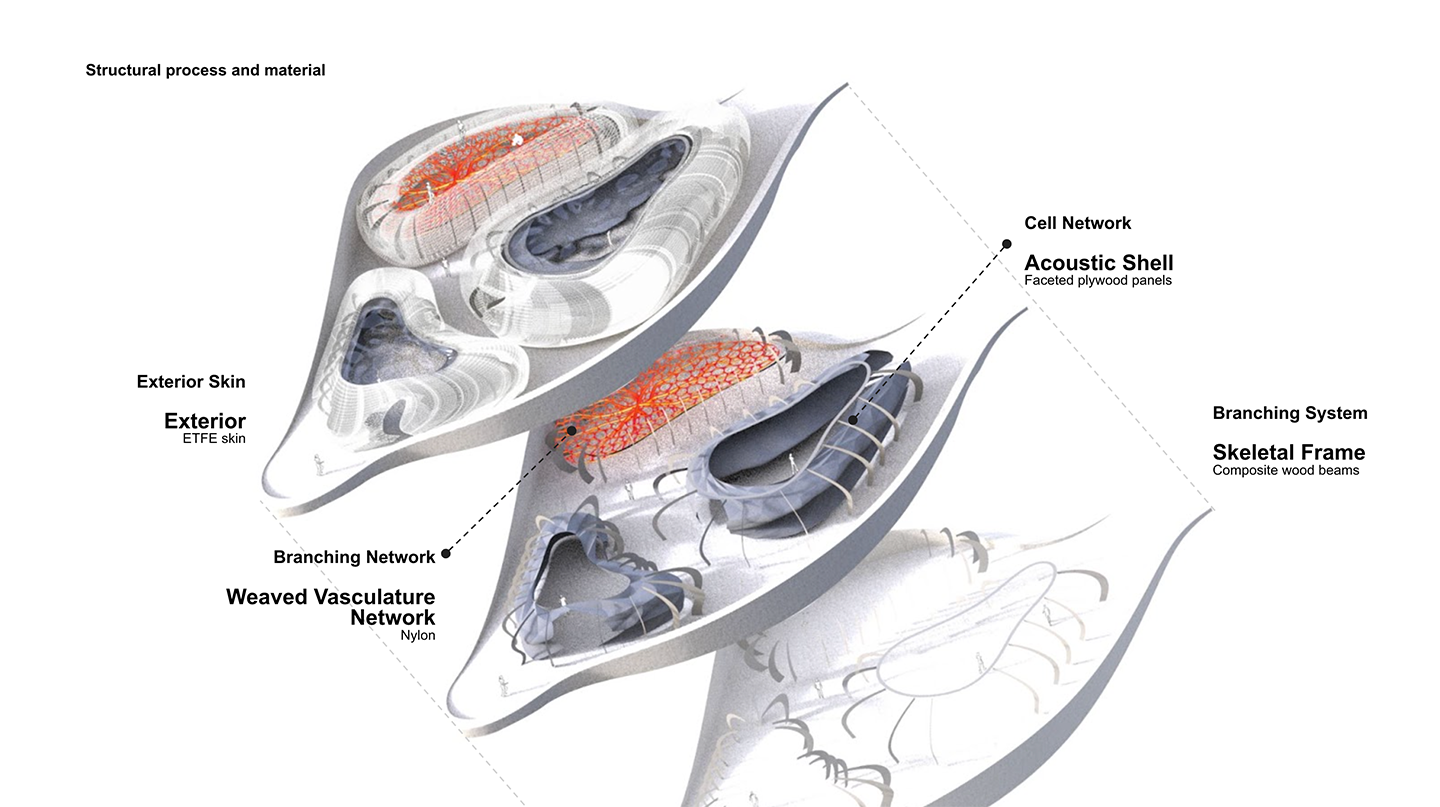

A diagrammatic rendering of the Watering Hole Pavilion. The project is a concert venue with a programmable skylight that filters light and sound into the visitor space. Inspired by branching morphogenetic vasculature networks, the pavilion is capable of interactively modulating the light and sound being played in the space. image / Hoon Yoon, Frances Gregor, and Nadia Catherine Samman

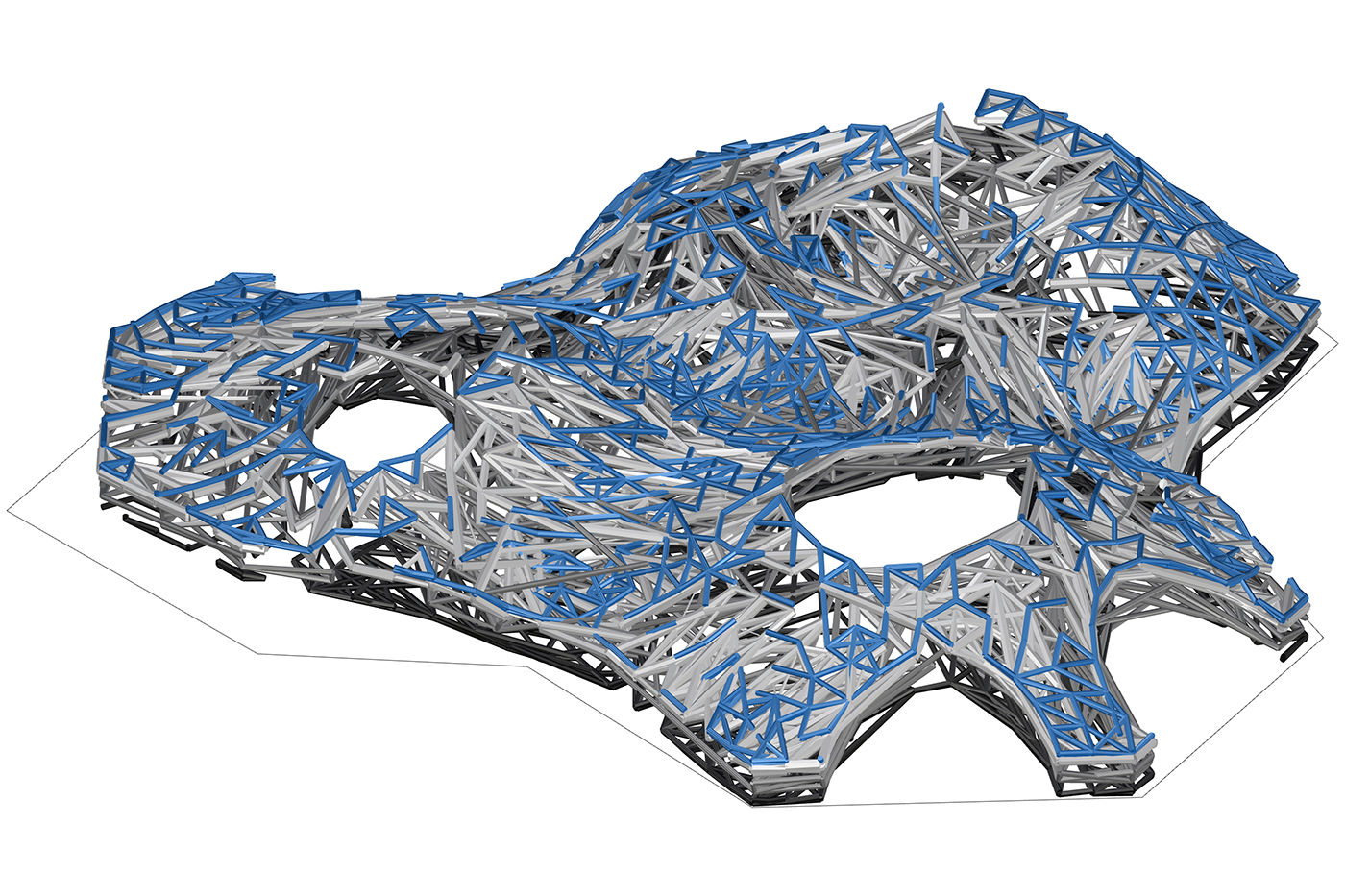

The Weaver Pavilion is powered by a custom algorithmic process that "weaves" multiple materials through predefined shapes. The algorithm is capable of using multiple streams of input data to drive the density and porosity of the weave globally and locally. image / Youngjune Lee, Moshe Borouchov, and Yiran Wang

A diagrammatic axonometric drawing of the Weaver Pavilion at a later stage of construction. The pavilion is printed using robots with a biodegradable material. The structure, once printed, using an excavated hillside as formwork, is lifted into place by small cranes. image / Youngjune Lee, Moshe Borouchov, and Yiran Wang

A rendering of a proposed pavilion with a unique floating design. The lattice is developed by the architectural team and the 3D-printed and sealed inflatables composed of recycled plastic are inserted by participants in the design process. As the inflatables reach a critical mass, the pavilion begins to take shape and elevates off the ground. image / Yehong Mi, Shuo Feng, and Sylvia Ding

Model of the Weeping Pavilion. image / Yangli Hu, Daniel Min, and Renzhi Hu

In early modules, students were tasked with investigating natural structures through drawing and procedural notation and using those generated patterns and structures as a basis for creating parameterized cut and fold patterns using digital fabrication methods. image / Yehong Mi, Shuo Feng, and Sylvia Ding

Stay connected! Follow @cornellaap on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn; and subscribe to our AAP bi-weekly newsletter.