Democracy Problems: Jae Shin and Damon Rich on HECTOR's Design Practice

Visiting AAP NYC architecture faculty Shin and Rich of the Newark, New Jersey-based firm HECTOR share thoughts on democratizing urban design and how they have learned from the US tradition of popular education.

Space Brainz (2017) simulated an "idealized un-idealized city" lurking in a rainbow grid world "where the art center becomes a laboratory for dissecting how power works through built space," Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, installation view. image / HECTOR

This semester's advanced urban design studio at the Gensler Family AAP NYC Center, Decks on Deck: Democratizing Urban Design, is led by designers Jae Shin and Damon Rich. Shin and Rich are partners at HECTOR, an award-winning firm recognized for practicing urban design, planning, and civic arts informed by traditions of visionary architecture, popular education, and community organizing.

Shin and Rich began their careers working as designers within municipal governments, including the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation and New York City Housing Authority, where democratic ideals meet the details of development. Their spring 2024 studio at AAP NYC engages in debates around democratizing design to study and speculate on design and development around and over New York City's Sunnyside Yards.

Lydia Li: In addition to being educators, you are also cofounding partners at HECTOR, a firm with a bold and somewhat mysterious name specializing in urban design, planning, and civic arts. Firstly, what does the name mean? What does it mean for the design work you do?

HECTOR: We are a modest practice with large ambitions, so we tried for a mighty and classical name, like the Trojan leader in Homer's Illiad! Also, as a verb, "to hector" means "to bully, intimidate, browbeat, harass, coerce, strong-arm, threaten, and menace," which are just a few of the communication strategies we have had to use in the process of urban design. It's never just a polite exchange, especially if you are trying to rejigger a design system with those who don't usually get a major say in a planning or building project. If there are people and interests that have never been part of the process, that's going to take a little bit of hectoring, right?

Between allies and antagonists, we're never alone in our agendas. And, the way spatial politics might include all kinds of actors — heroes, paper pushers, villains — was also something we had in mind when registering the name HECTOR. It also stands for a few different phrases like How Every Culture Threatens Our Righteousness.

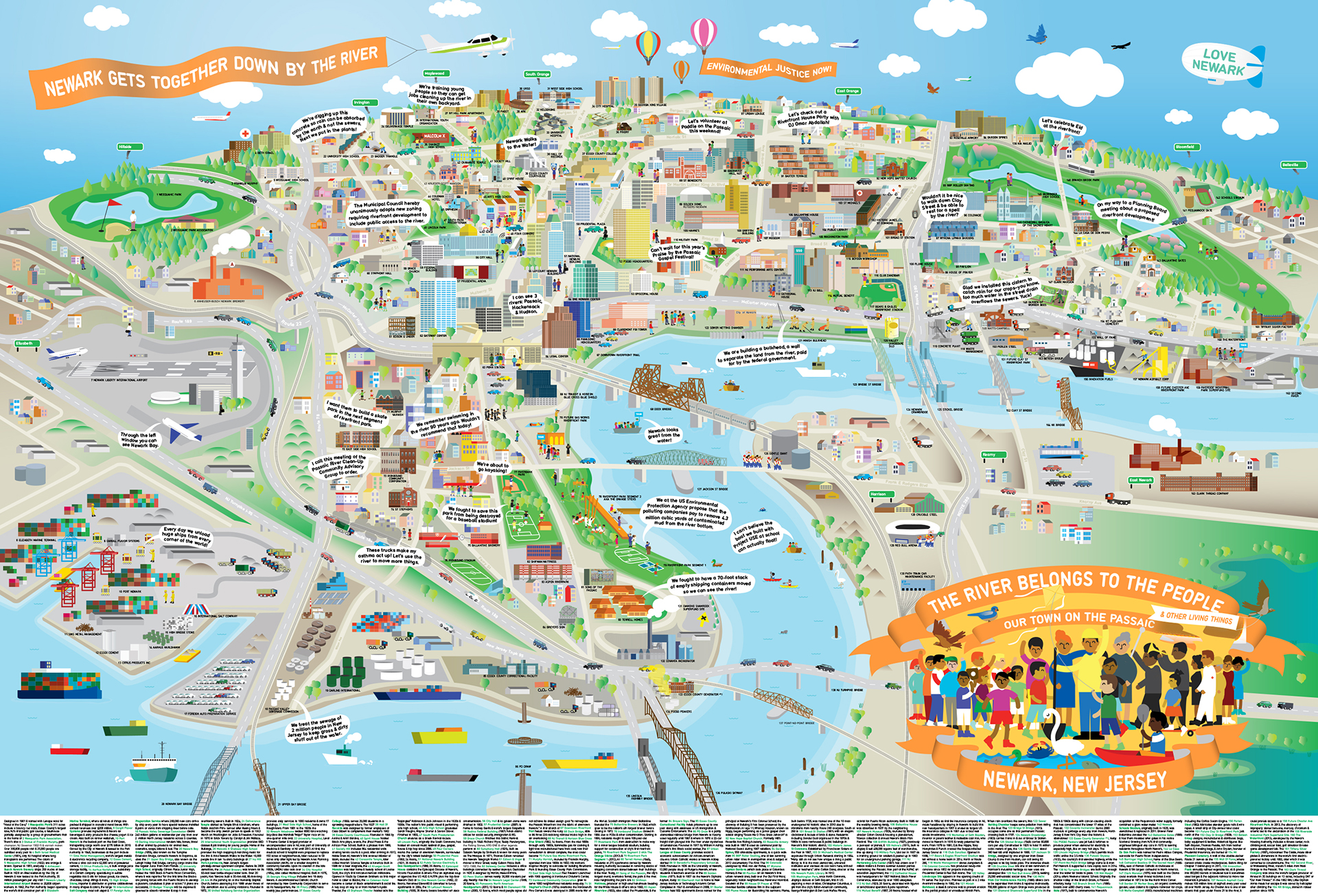

Newark Riverfront Park, with public spaces along the Passaic River informed by 30 years of organizing for environmental justice. image / HECTOR

LL: Given Jae's prior experience as a fellow at NYCHA, and Damon's previous role as planning director and chief urban designer for the City of Newark and founder of the Center for Urban Pedagogy (CUP), how do these experiences affect your shared approach to designing for cities, people, and civic spaces?

HECTOR: With our shared experience as designers in the public sector, we've had the chance to see first-hand how things happen — how a park design or a zoning plan gets shaped by organizers, politics, money, and force. These experiences make us skeptical of the growing participation industry and some generalized calls for participatory or responsible design. For us, the real question is, responsible to whom? Maybe we don't need responsible design so much as a serious reworking of "to whom" design responds.

We're inspired by architects like Lawrence Veiller, who worked as a municipal building plan inspector, designed model tenements, organized affordable housing design competitions, and wrote housing regulations. Because of work like his, even with elite bias and blind spots, architecture gained new social qualities and possibilities. Cities could democratically decide on rules for building themselves, rendering otherwise mundane architectural features like fire escapes, air shafts, and hallway bathrooms as figures of collective will for shaping the environment.

Rendering from the Cody Rouge & Warrendale project, a plan for housing, transportation, public spaces, and local businesses informed by a YOUTH-CENTRIC Neighborhood Framework that documents a comprehensive, community-driven, government-endorsed vision with specific proposed projects for Detroit’s western neighborhoods, which are home to 36,000 residents, with over 1/3 under the age of 18. image / HECTOR

LL: In many of your projects such as Newark Riverfront Park and Cody Rouge & Warrendale YOUTH-CENTRIC Neighborhood Framework, working with teenage residents is crucial to the design process. Why teenagers, and in what form were they engaged in this process?

HECTOR: Teenagers are seriously tuned into the meanings and shades of human judgment and domination. When prepared and given space, they don't hesitate to question the outlooks and motivations of people like us entrusted to design, build, and operate their city's public spaces. This disillusionment and pleasure in violating adult discretion can really energize the start of a design process.

For example, on Detroit's far west side in Cody Rouge and Warrendale, where HECTOR led a youth-centric development plan, we worked with nine teenagers serving as Neighborhood Framework Investigators who analyzed and documented the possibilities and propaganda of an official neighborhood planning process. Tramping around the city to meet park advocates, civil servant project managers, elected officials, real estate developers, and neighborhood organization leaders, together we conducted interviews and site visits documenting the neighborhood's physical and social contexts. After eight weeks, the group shared their findings in an official public kick-off meeting that commenced the broader planning process. Their work continued as part of the project's Organizational Steering Committee, meeting monthly to discuss potential projects, share knowledge, coordinate plans, and steer planning and design work with residents.

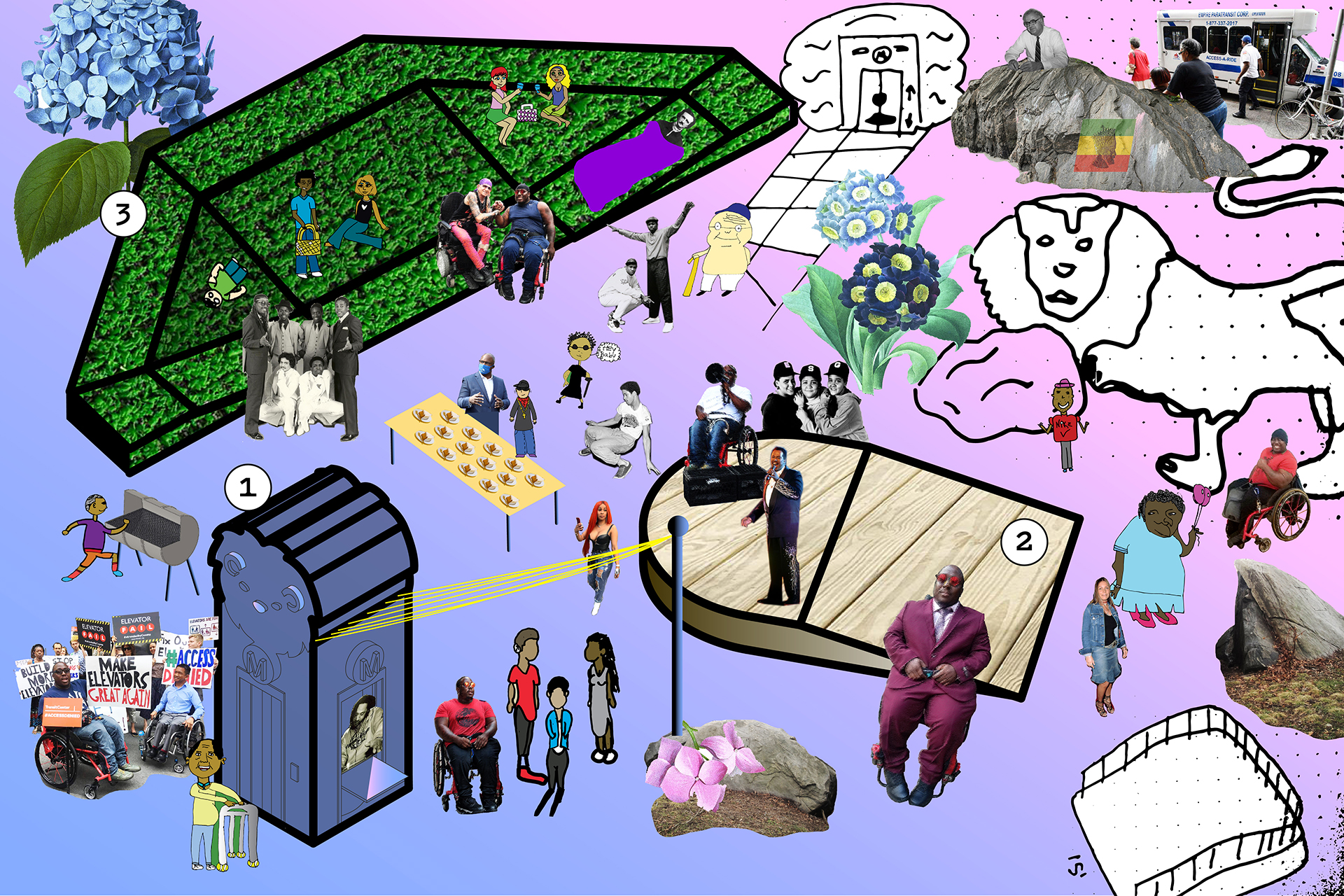

Curb Cut Fete (2021), a HECTOR collaboration with disability advocate Dustin J and Curbed for a celebration in the Bronx with monumentalized chill-out and socializing equipment that pays homage to accessibility advocates in the form of 1. a subway elevator head house DJ booth, 2. a ramped partying and speaking platform, and 3. a curb cut lounger. image / HECTOR

LL: I'm curious about how more communities might question the power of those who design, build, and run cities. Let's start with the common conflict between top-down and bottom-up approaches to designing urban spaces. How do you understand and then reconcile the two in a productive way?

HECTOR: In our practice, we usually find that dichotomies of top-down vs. bottom-up can't really capture the complexity of spatial politics at play. At this time of mainstreaming community design, participation, and equity talk, when many active residents are sick of sticky dots, Post-it notes, and "What I'd Like In My Neighborhood Is [Blank]" signs, when faking community engagement is so frequent that it's easy to lose the point, and do-gooderism easily slides into managing the appearances of doing good, we should remind ourselves there is no access to democratic design without disassembling expertise and generatively de-idealizing design. There's a big difference between "show us what you want for your place," and developing the capacity to make group decisions for all of us.

Rather than carry on community design in the margins, our collective goal should be to communitize all design. And, rather than continue with the often-celebrated "community engagement" scope of work like designing tools/games, or fantasies of "gaining the trust of the people on the ground," this is a key objective our studio this semester titled Decks on Deck: Democratizing Urban Design.

AAP NYC studio Decks on Decks: Democratizing Urban Design with Jae Shin (left) and Damon Rich, including a diagram showing "who decides what gets built in NYC." image / Zijian Xu (M.S. AUD '24)

Students Yiyun Luo (M.S. AUD '24) (left) and Zijian Xu (M.S. AUD '24) presenting mid-term work at AAP NYC. image / provided

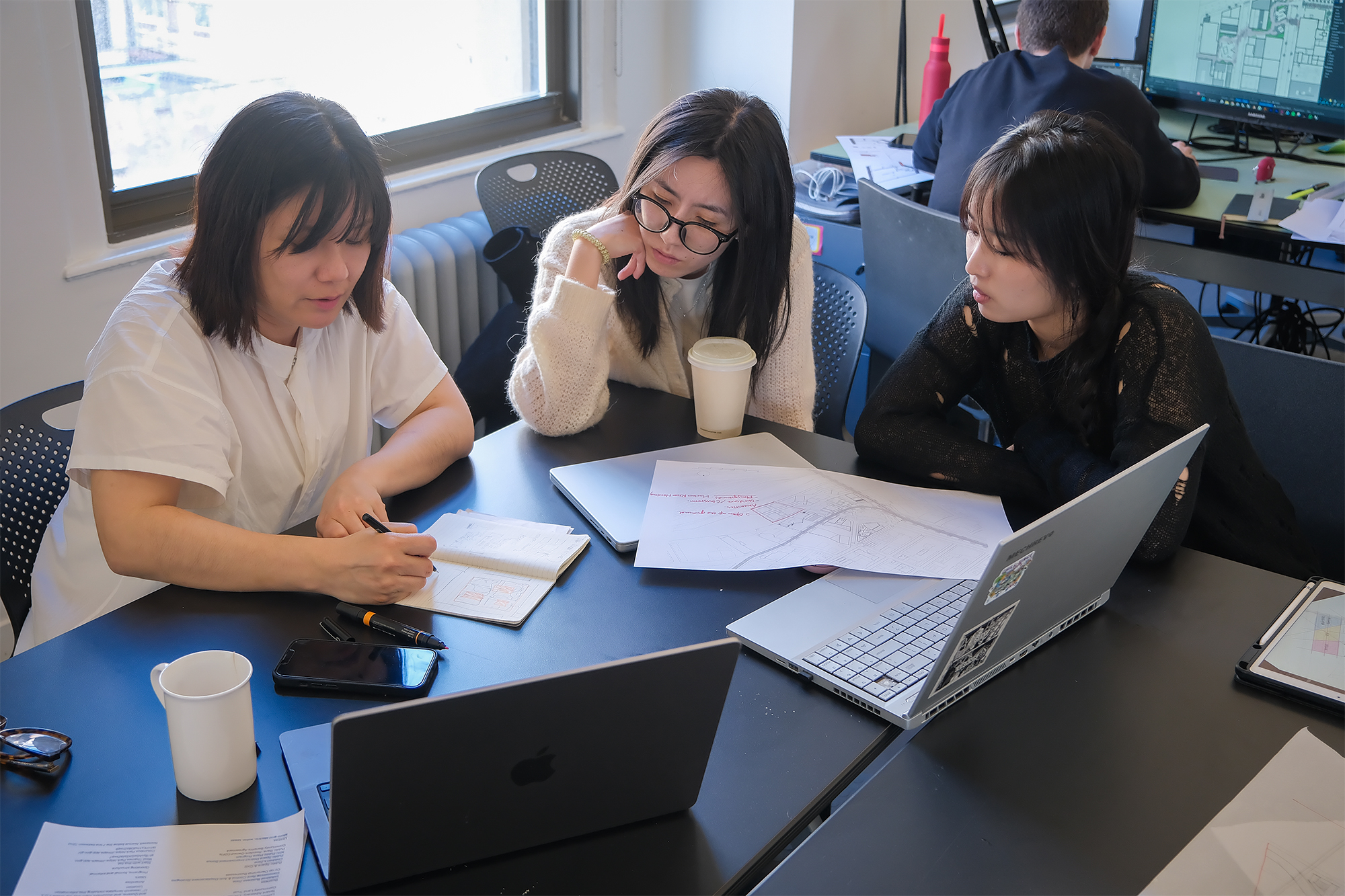

A review of work in progress with visiting faculty Jae Shin and M.S. AUD students. image / Zijian Xu (M.S. AUD '24)

Visiting faculty Damon Rich viewing a collective photographic survey produced by students in Rich and Shin's spring 2024 Decks on Deck: Democratizing Urban Design studio at AAP NYC. image / Zijian Xu (M.S. AUD '24)

AAP NYC studio Decks on Decks: Democratizing Urban Design with Jae Shin (left) and Damon Rich, including a diagram showing "who decides what gets built in NYC." image / Zijian Xu (M.S. AUD '24)

LL: Can you offer some advice for students and early-career designers on how to get started working on democratizing the design process with resident communities?

HECTOR: We recommend considering work with municipal government agencies, community development corporations, and neighborhood organizations as great ways to build up your perspective on how design intersects with broader fields of spatial politics. If you're interested, we've discussed this more at length in a conversation published as "Design for Organizing" in the book Spatial Practices: Modes of Action and Engagement with the City, edited by our friend Melanie Dodd in the UK.

LL: At AAP NYC, we're fortunate to have practitioners who double as educators (and vice versa). In your studio, we learn technical skills for urban design practice but also often analyze and discuss the role and impact of different decision-makers. As designers who take on multiple roles, where do you locate yourself?

HECTOR: Rather than seeing our disciplines as bags of goodies to deliver to the public, we try to imagine ourselves as being invited to a big party where, though we are shy, we try hard to strike up conversation with anyone who will talk to us. We try to understand architecture and design problems in the context of democracy problems: how we make the decisions that we have to make together. We feel lucky to work with and learn from local governments, community organizers, advocates, builders, financiers, and bureaucrats.

This semester's Advanced Urban Design studio at AAP NYC includes students John Albert Conrad (B.Arch. '25), Yongcong Gou (M.S. AUD '24), Ruoxi Li (M.S. AUD '24), Vicky Luo (M.S. AUD '24), Shevaun Kasi Mistry (M.Arch. '25), Jishnu Murali (M.S. AUD '24), Richa Surati (M.S. AUD '24), Chu Han Tarn (M.S. AUD '24), Gina Wei (M. Arch. '24), and Zijian Xu (M.S. AUD '24).