Glenn Ligon is an artist who has pursued an incisive exploration of American history, literature, and society across bodies of work that build critically on the legacies of modern painting and conceptual art. As the spring 2024 guest speaker for the John A. Cooper Visiting Artist Lecture Series at AAP, Ligon will give a public artist talk on March 5. The series was created with a gift from alumnus John A. Cooper (B.F.A. ’97) to bring distinguished artists of particular renown to the Ithaca campus to engage art students and the art community through lectures, studio visits, seminars, and individual critiques with B.F.A. students.

Paul Ramírez Jonas

When I met you, I think at the very end of the ’80s, and you were already doing the work you are doing to this date — you’ve been very consistent — there was no guarantee that the idea of plurality, of multiculturalism, and making space for other folks in a white art world was going to succeed, right? It wasn’t a given. And I feel that in many ways it has done so beyond any expectations I had. And yet, your work has remained like a Cassandra. When I’m thinking of the backlash we’re going through, your work doesn’t seem caught unaware: “Oh my God. What a surprise!” Even as you ascended into the canon of contemporary art and others came behind you, your work has remained very skeptical.

Glenn Ligon

Interesting. I think that’s a good characterization of myself personally, but it’s hard for me to see that in the work, though I know it must be there because it feels true to who I am and I feel like the work is not so divorced in most cases from who I imagine myself to be.

My brother and I grew up in the South Bronx and my mother sent us to a private school from first grade onwards. It was mostly white kids, and she would say things like, “White people aren’t everything.” So in my head when you were talking, I was thinking, “The white art world wasn’t everything.” There were always other art worlds, and there still are.

Part of what has been interesting to me over the past couple of years is to think about how those other art worlds function. David Hammonds was showing in the Brockman Gallery in LA in 1975, and that was a Black-owned gallery with a Black constituency. Now, I didn’t say he made any money, but there were other art worlds. But at the time that I got out of school and was trying to show a bit like that, I think I was a bit myopic and thought, “Oh, there is only one art world and all those galleries are in Soho.” It’s like, okay, Basquiat has a gallery. Nobody else, but let’s see if we can break that shit open.

I remember when I first joined Max Protetch Gallery — this was ’91, ’92 — and people saying to me, “Oh, you’re the first, ” like Jackie Robinson. And I was the first kind of, but a lot of people were like that. Lorna Simpson, you’re the first in that gallery. So there was that breaking open, but you had to be a bit skeptical, I guess, because it felt like it could all be taken away, very Adrian Piper-like. Everything will be taken away, including this spotlight moment, because we’ve had examples of that. Artists that we celebrate now — Sam Gilliam, Jack Whitten — they had lobby shows at the Whitney Museum in the seventies and then boof, you didn’t hear from them, commercially, museum-wise, for 30 years.

Paul Ramírez Jonas

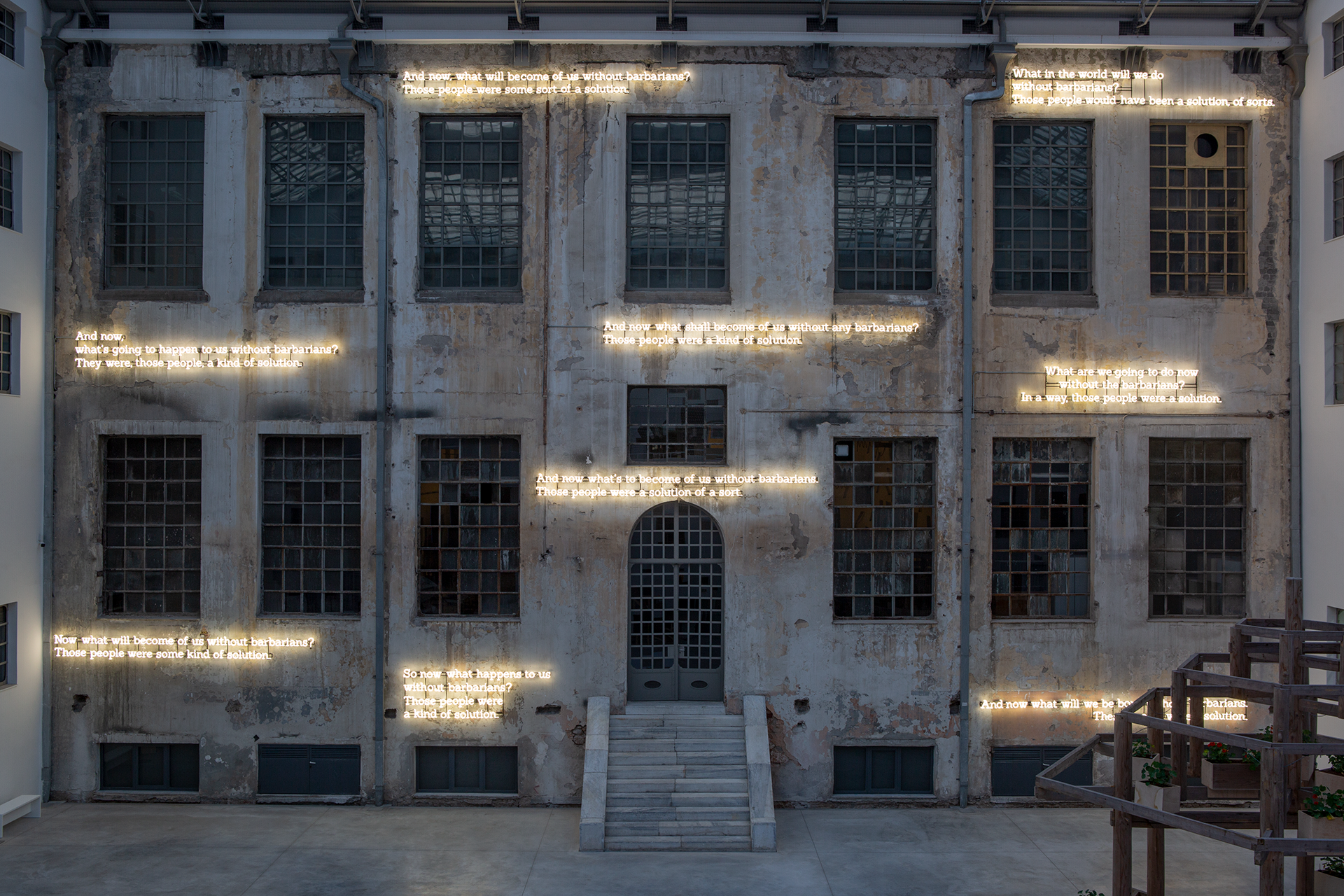

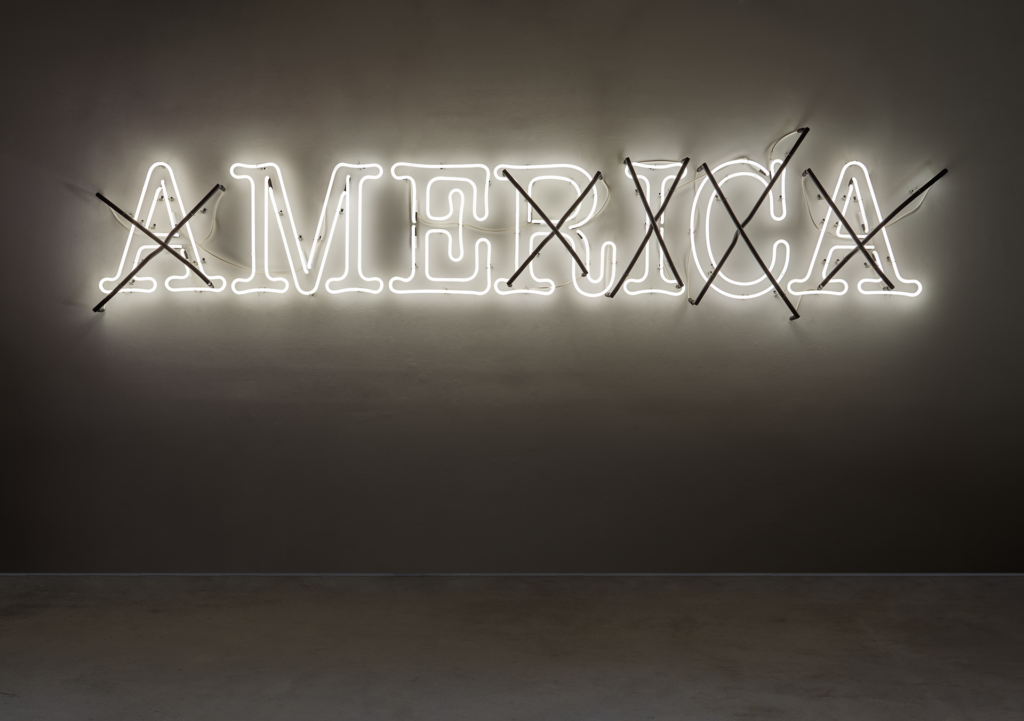

On the one hand, to me that’s the nature of structural racism. On the other hand, it’s also the nature of the art world. I always felt that race was going to be the thing that the art world was not really going to be able to handle. Not because the art world is a special world unique and apart from the wider world — it’s actually just exactly like the world. And still, I had a moment of optimism; but back to your work. I think about America, the neon piece. It still seems like a warning, not a celebration in any sense.

Glenn Ligon

Well, you know, we have been in fragile times around our democracy in other moments, and I think this is a particularly fragile time. I think about those America neons I guess the way I think about lots of things — it’s material to be played with. So the idea of America is material to be turned to the wall or painted black or rotated or obscured or whatever because in this country we have this notion that we understand what all these terms mean, and I think in the last couple of years we’ve realized, no, we have very fundamentally different ideas of what America as a democracy means, what ideas are behind that word. We have very fundamentally different ideas about that. So it feels like it’s a bit up for grabs, and I don’t know who’s going to win that struggle.

Paul Ramírez Jonas

It’s interesting, because back to my point that the art world is not a world apart, a magical kingdom, now that I’m more entrenched in academia than ever, I’m seeing things happen that I never dreamt could happen here. This is also not a magical kingdom outside of the world, and it makes me wonder if you already see any signs of that fragility in the art world as we know it, or at least in the normative art world.

Glenn Ligon

Yes, I think there’s a lot of self-censoring going on. I’ve heard that collectors have been calling artists to say, “Did you sign XY petition?” I’m on several boards and a fellow board member said that she’s getting frantic calls from arts organizations because their funding is in jeopardy depending on what their social media presence says. Literally, we’re going to take away your grant unless you delete the solidarity support that’s on your website.

Paul Ramírez Jonas

For over a decade, I’ve been really interested in artists who are turning the table on the extractive nature of the art world. They see the art world itself as a thing they can extract resources from and put back into their communities, playing a double game. I admire them because I imagine them to be a little bit more pragmatic about the art they make. They know why they’re making art for the art world, because they need those resources to bring back to their other projects.

Glenn Ligon

There has been a boom, as you said, in artists using those resources, and they are very clear about why they are making work because they are funding exhibition centers and residencies. I am thinking about Mark Bradford in LA, Art + Practice, Titus Kaphar in New Haven (NXTHVN), Derrick Adams in Baltimore, Wangechi Mutu in Kenya, on and on. I am on the board of the Rauschenberg Foundation, but all of that was started after Bob died. These artists are saying, “Let me use the resources from the sales that I am making right now and establish a grant-making program or a residency,” which, to me, is inspiring and also just a little exhausting because I can’t even manage my studio much less the idea that I am going to start a residency program. Totally fascinating to me, that real sense of commitment to working with specific communities. But that seems like a fairly recent phenomenon, and maybe in part that’s because, as young artists, they are making enough income to support that, which 30 years ago, 40 years ago, you would have been hard-pressed to be ambitious on that scale given the income you were making from your work.

Paul Ramírez Jonas

The consolidation of wealth and all of that may be value-neutral until you see some people are using that concentration of wealth for more than just personal gain. There is some kind of hope there.