Building Labor Into Architectural History

"Labor Un:Imagined," this semester's Preston H. Thomas Memorial Symposium, brings scholars together to explore how the field has addressed building labor in architectural history and pedagogy.

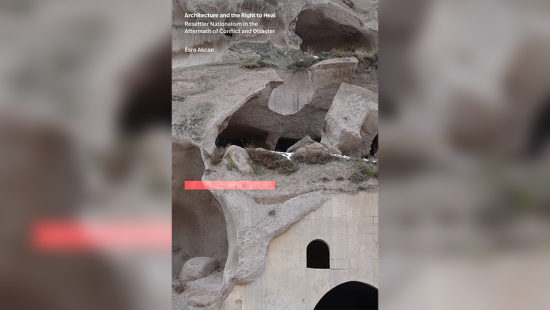

Wood formwork under construction, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1959. image / Courtesy of Félix Candela Architectural Records and Papers Collection, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Drawings and Archives, Columbia University

When looking at a building, the design, the materials, and the technology that went into its construction are generally apparent. But what about the physical labor that brought it into being? Though it remains indexed within the architectural artifact, once workers leave a construction site, they often also vanish from the historical record. These absences have a deep impact on the way architectural modernity is understood and on the ways we explain and teach its history.

"If we want to engage with a decolonial approach to architectural history, labor is a concept crucial to understanding power structures," notes Assistant Professor María González Pendás, a historian pursuing these ideas in her work and who brings them before the College of Architecture, Art, and Planning with "Labor Un:Imagined," this semester's Preston H. Thomas Memorial Symposium on March 7 and 8. Why don't architectural historians write more about building labor? Through conversation around current research presented by scholars working at the forefront of this question, the symposium will explore the methods, archives, and narratives that historians have at their disposal to better address this void and encourage a deeper understanding of the importance of this work.

Wood formwork under construction, Cuernavaca, Mexico, 1959. image / Courtesy of Félix Candela Architectural Records and Papers Collection, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Drawings and Archives, Columbia University

The Construction Site as a Site of Knowledge Production

The construction site has long served as a site of exploitation based on race and gender, but it has also been a unique site of knowledge production that has encouraged social change and political possibility.

"As a historian, I want to better understand this dual condition," says González Pendás. "Looking closely at these scenarios helps us understand how the conditions of architectural production have changed and can change social relations."

To that end, invited guests such as migration scholar Sarah Lopez from the University of Pennsylvania will showcase the work of stone workers straddling the Mexico/US border. Silke Kapp, a professor at the Federal University of Minas Gerais, will share her translations of the theories of Brazilian architect Sergio Ferro and his Marxist call to reimagine labor. In addition, Katie Lloyd Thomas of Newcastle University will present research on female factory workers producing building materials in the UK, and Drexel University's Amy E. Slaton will speak about the racial implications of skill building in the US building industry. These and other experts will discuss labor histories and colonial legacies in Mumbai, Sierra Leone, the Phillippines, and beyond, taking questions after their presentations and opening a dialog across research areas.

Worker at Goldwin Smith Hall cornerstone ceremony, Cornell University, October 19, 1904. image / Building Files, Goldwin Smith Hall, Division of Rare Books and Manuscripts, Carl A. Kroch Library, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York

Who Built Your University?

Complementing the discussion, an exhibition in Cornell AAP's Bibliowicz Family Gallery will bring these global ideas into hyper-local focus and dive into the archives of construction history and labor dynamics at Cornell, a little-known aspect of the university. Several students who took part in an initial course on the topic and, inspired by the research group Who Builds Your Architecture?, pursued the subject further, have examined worker records and considered the relationship between land appropriation, labor, and student unions in greater depth.

The Takeaway

González Pendás hopes that symposium participants trigger a collective rethinking of the methods and assumptions currently relied upon by the discipline and that attendees have a relatively uncommon opportunity to experience firsthand the imaginative and critical practice of history.

Visiting Critic Emma Silverblatt, who is coordinating the symposium, underlines some of its broad implications. She explains that "as practitioners, we need to ask ourselves: What is our role in this co-creation process with the labor of building something? How can we make this equitable? By considering the historical record, maybe we can pull the labor dimension into the conversation and question what we celebrate as architects."