Bridging Worlds

Caroline O'Donnell, architecture's incoming chair, on the discipline's unique ability to shape-shift as design interfaces with environmental conditions, performance, and modes of communication.

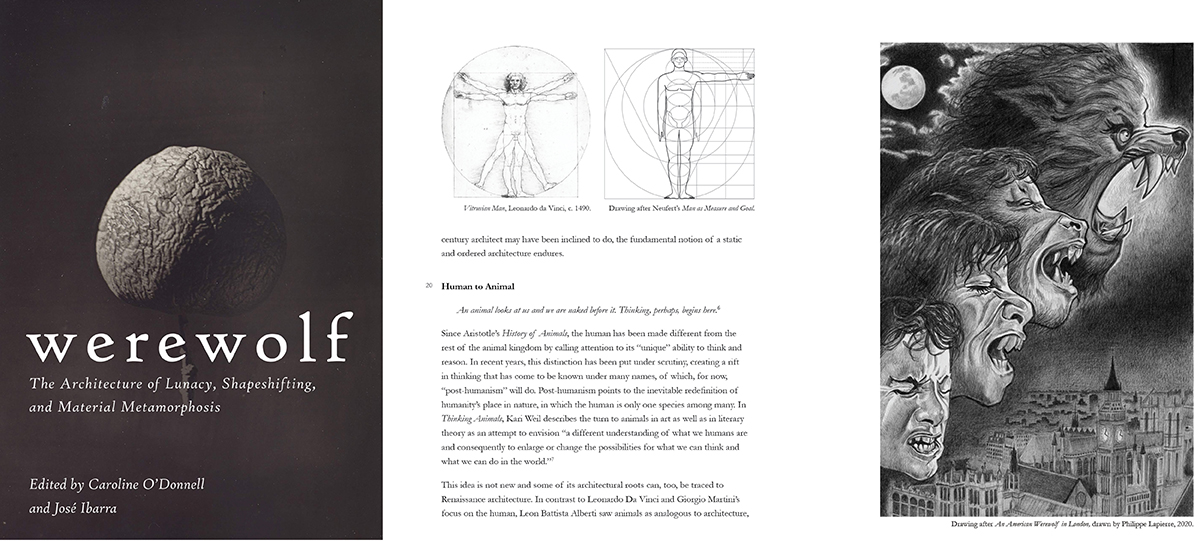

Caroline O'Donnell is currently the Edgar A. Tafel (Associate) Professor of Architecture and director of the M.Arch. program at AAP. In her 12 years at Cornell, she has taught core studios in the B.Arch., M.Arch., and MSAAD programs, as well as option studios on topics ranging from sustainability and circularity, to conflict and global identity. O'Donnell is the former editor-in-chief of the Cornell Journal of Architecture and coauthor/editor of three books to date. Her third title, Werewolf: The Architecture of Lunacy, Shapeshifting, and Material Metamorphosis with José Ibarra, will be released via AR+D/ORO Publications this fall. She is also a licensed architect and principal of CODA, an award-winning practice known for projects such as Party Wall, winner of the PS1 MoMA Young Architects Program in 2013, and the inclusive addition at the Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts.

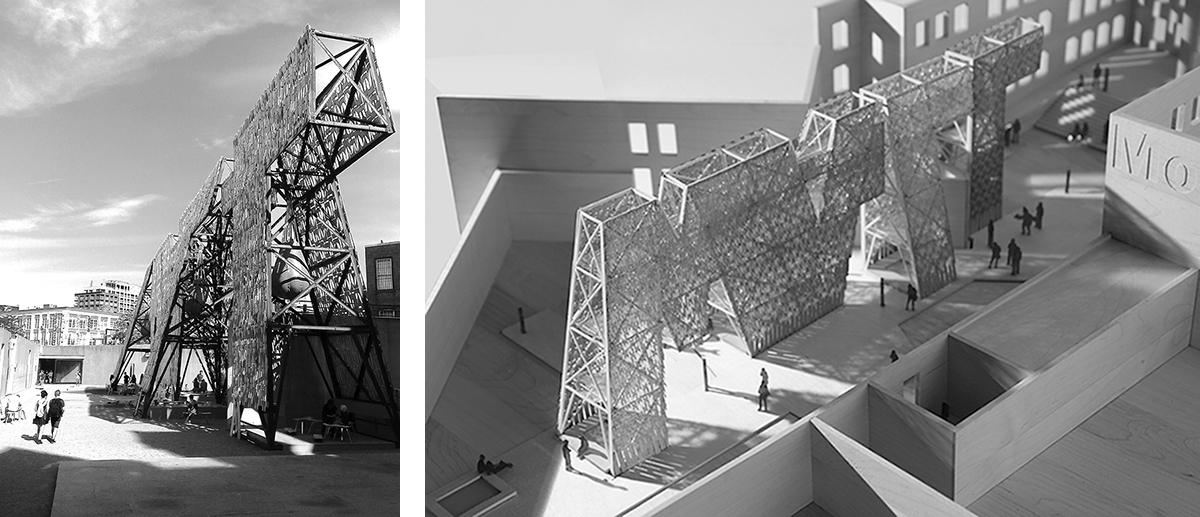

Party Wall (2016), produced with salvaged wood off-cuts from the Comet Skateboards production facility for the MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program, Queens, N.Y. images / CODA

Party Wall (2016), produced with salvaged wood off-cuts from the Comet Skateboards production facility for the MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program, Queens, N.Y. images / CODAWhen did you know you wanted to be an architect — where did it all start?

I never thought about being anything but an architect. I grew up in Ireland and spent my childhood playing in half-built houses and half-demolished ruins. The power of nature and its interconnectedness with architecture was palpable — strong winds, rain clouds, moss growing on walls, burning the earth, building with local stone and thatch — so it makes sense that my current practice is very much about the intersection of those worlds.

In preparing for a career in architecture, what were some strong impressions or valuable lessons you took away from your education that significantly shape your thinking and practice?

During my B.Arch. at the Manchester School of Architecture in England I specialized in "bioclimatics" — the relationship between architecture and the environment. When I went to Princeton for my master's degree, I had a quite formalist education that explored questions of meaning in architecture. Most important to me was the discrepancy between those two worlds — between architecture's ability to perform within the environment, and its ability to communicate. The strange place between the two is exactly where my practice exists. My work asks: If architecture can communicate, how can it communicate notions of its relationships to the world and provoke new thoughts and practices?

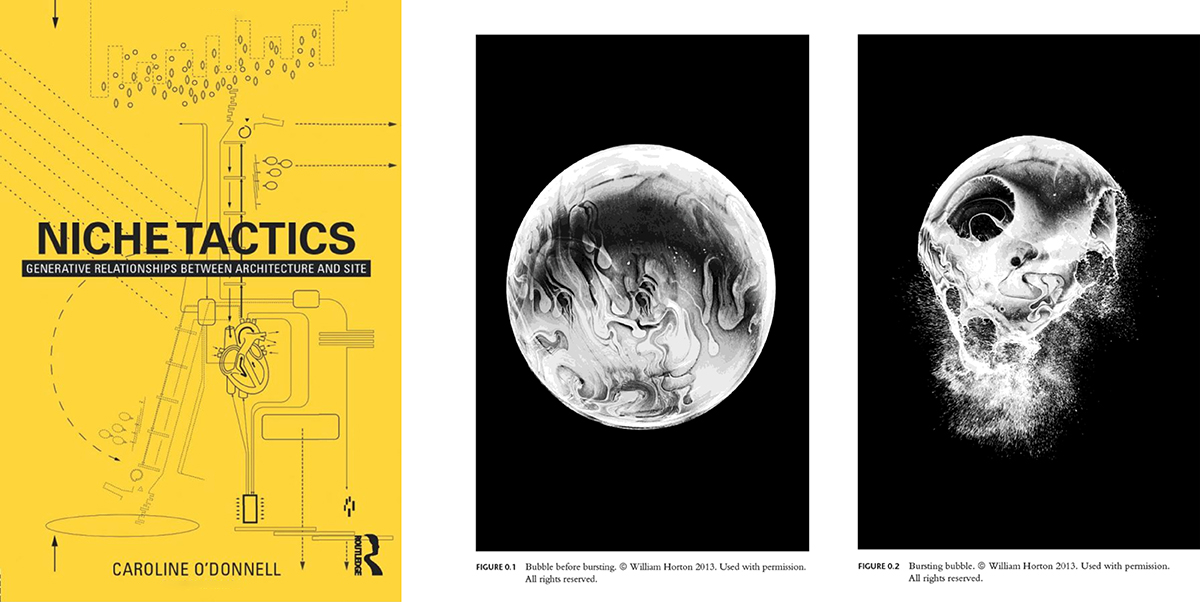

Niche Tactics: Generative Relationships between Architecture and Site (Routledge, New York, 2015) cover and sample spread of inner pages. images / provided

Niche Tactics: Generative Relationships between Architecture and Site (Routledge, New York, 2015) cover and sample spread of inner pages. images / providedYour first book, Niche Tactics: Generative Relationships between Architecture and Site, touches on these issues.

Yes, Niche Tactics is about bridges between the formal and the ecological.

The book focuses on moments where the relationship between those two worlds has been particularly productive (or, counterproductive). This relationship applies to architecture as well as fields outside of the discipline, and so Niche Tactics, in parallel with my design and research practices, searches for a strategy that allows form to be generated as a response to and in dialogue with its environmental niche.

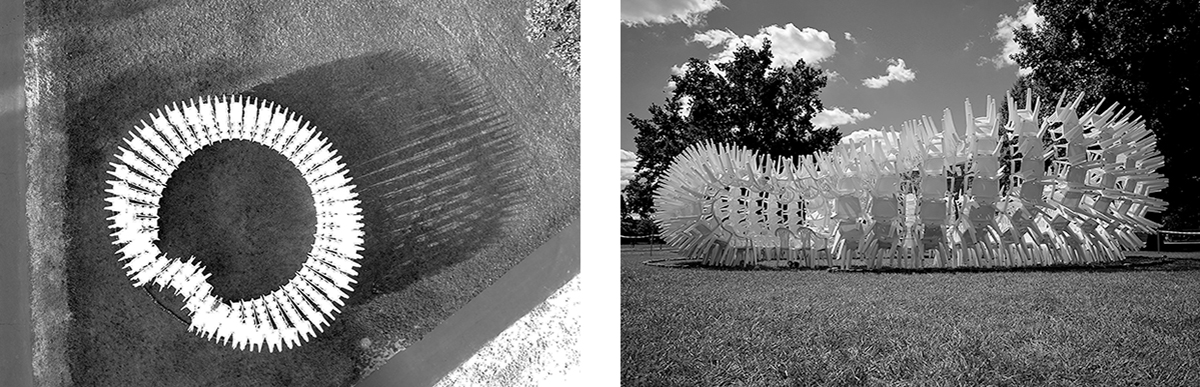

Urchin (2016), a pavilion constructed on the Cornell Arts Quad using borrowed plastic patio chairs as part of the 2016 Cornell Council for the Arts Biennial, Object Empathies. image left / Thomas Campanella; image right / Joe Wilensky

Urchin (2016), a pavilion constructed on the Cornell Arts Quad using borrowed plastic patio chairs as part of the 2016 Cornell Council for the Arts Biennial, Object Empathies. image left / Thomas Campanella; image right / Joe Wilensky

Your built work operates at an unusually broad range of scales — it can be a bench, a building, a city. Why is this important?

Timothy Morton's concept of the hyperobject is helpful to me when thinking about design. A seemingly innocuous object, when considered in terms of its environmental and social impact globally and locally, becomes a complex web of scales in space and time, and I believe that the ability to zoom in and out of spatial and temporal scales is fundamental to good design.

If I think about an object in relation to its environment, I will always think about it at multiple scales. For example, a chair might seem to be at the scale of the body, but its materiality is operating at a molecular scale while its fabrication and afterlife (through reuse or recycling) is operating at a global scale. And vice versa, a building or a city also operates at micro scales that are important to integrate into the design process.

Left: Primitive Hut (2017), a lattice structure designed and constructed by OMG (O'Donnell Miller Group) around four maple samplings that will both grow and decay over time; right: Evitim (2018), a complementary structure built of Primitive Hut's off-cut material at the same site, Art Omi in Ghent, N.Y. images / OMG

Left: Primitive Hut (2017), a lattice structure designed and constructed by OMG (O'Donnell Miller Group) around four maple samplings that will both grow and decay over time; right: Evitim (2018), a complementary structure built of Primitive Hut's off-cut material at the same site, Art Omi in Ghent, N.Y. images / OMGAnd these objects, they have curious names.

The naming of things is an obsession of mine. We can communicate a lot with a title, like an image. Party Wall, for example, referred to both the program of the party itself for the Warm-Up Dance Festival at PS1, but also to the multiple alternative constituents of the shared "wall." Tripe says a lot with one little word, referencing nose-to-tail consumption. And, Primitive Hut (an OMG project in collaboration with Martin Miller) references the well-known image by Laugier that calls for a return to architecture operating symbiotically with nature. In this project, we took that prompt literally and designed a structure that would both grow and decompose. Evitim, (Primitive Hut's twin sister, and another OMG project located on the same site at Art Omi), uses the leftovers from the fabrication of Primitive Hut and, as a result, its name is a partial inversion of the word "primitive."

Tripe (2018), an "offally small library," winner of the Buffalo Architecture Foundation's Little Free Library Competition, located in the Esser Street Garden, a community garden in Riverside, Buffalo, N.Y. image / CODA

Tripe (2018), an "offally small library," winner of the Buffalo Architecture Foundation's Little Free Library Competition, located in the Esser Street Garden, a community garden in Riverside, Buffalo, N.Y. image / CODA

Many of your projects appear to play with surfaces and materials — suggesting that there may be as much seen as unseen in both the material and form. Can you explain?

The playfulness with materials is relatively constant in my work but the motivation has evolved. Early on, I was interested in perceptual psychology, in particular the notion of "affordances," coined by J.J. Gibson in the 1970s. Affordances permit the primary perception of the performance or function of an object. In my earlier work, I was interested in manipulating perceptual affordances by using materials in unconventional ways to provoke thoughts on the true meaning or provenance — the bigger picture — of an object or a material. Today, I focus on how affordances might change as an object becomes "waste," and how we might rethink design in relation to the afterlife of objects and materials. Recently, with colleagues Felix Heisel and Dillon Pranger, as well as Dirk Hebel, I developed a series of studios on notions of waste, resulting in the book The Architecture of Waste: Design for a Circular Economy (Routledge, New York, 2019), which includes several designs using waste by students in the architecture programs at AAP and Harvard GSD.

Werewolf: The Architecture of Lunacy, Shapeshifting, and Material Metamorphosis (AR+D, Los Angeles, forthcoming) cover and sample spread of inner pages. images / provided

Werewolf: The Architecture of Lunacy, Shapeshifting, and Material Metamorphosis (AR+D, Los Angeles, forthcoming) cover and sample spread of inner pages. images / providedWhat are you working on currently?

José Ibarra and I are just now finalizing our Werewolf book. Werewolf: The Architecture of Lunacy, Shapeshifting, and Material Metamorphosis is both a monograph and a manifesto that explores the transformation of architecture through its lifetime — whether mechanically, materially, or perceptually. The shift from passive buildings to reactive structures is now imperative, as climate change and political turmoil exacerbate the unpredictability of environments. Werewolf expands on the architect's agency to critically address political, social, and environmental unrest. These ideas are studied through architectural projects and framed by critical essays by Jesse Reiser, Greg Lynn, Jimenez Lai, Spyros Papapetros, Kari Weil, as well as the editors.

In tandem with that, we have some interesting research projects happening in the Ecological Action Lab (for example, experiments with nose-to-tail techniques and materials like potato starch and manure as building materials), as well as some more building-scale projects in the office, like the recently completed inclusive addition to the Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts.

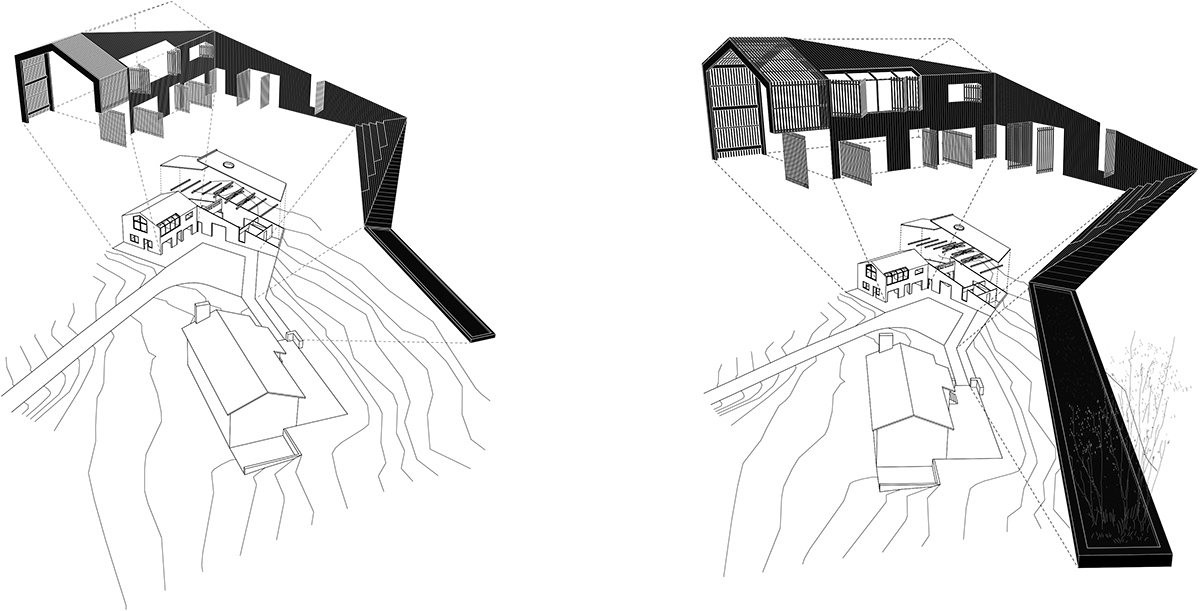

The Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts inclusive addition (2021) in Ithaca, N.Y. images / CODA

The Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts inclusive addition (2021) in Ithaca, N.Y. images / CODAIn your view, has how architects design fundamentally changed in the context of our particular moment — of environmental crisis; of movements for greater equity and justice; of evolving and emerging technologies?

Architecture is certainly beginning to address these issues, but our discipline is still overshadowed by the ghosts of the last century and all the baggage that was handed down to us through our educators and theirs before them. Imagine, there was a time when "orders" dictated how columns should be made according to the rules of proportion and perception. Even in the last century, adherence to the rules and doctrines of the masters was the norm. Today, I think we can challenge the discipline in fundamental ways that were not conceivable in the past. We are in a position to question the relationship of buildings to climate change and social justice as well as to machines and virtuality. These issues prompt the big questions of our moment, and while the pandemic has been incredibly difficult for many people in many different ways, the silver lining is that it has certainly precipitated a thoughtfulness about the global status quo that affords an opportunity to rethink our discipline.

I am excited about the parallel between the idea in Werewolf that architecture can transform, and, that there is the same possibility in the discipline itself. I think we are at a point where we can let go of common preconceptions of what architecture was or is to ask what it could and should be. We need to use this time to study and discuss the questions our time asks of us, and as a consequence of that study, we need to translate those emerging ideas to new kinds of form and material, embracing the challenge of designing lasting change and building better worlds.