How Do We Make a Public?

Paul Ramírez Jonas, incoming faculty and chair of the Department of Art, on art practice, public exchange, and pedagogy.

Paul Ramírez Jonas is a Brooklyn–based social practice artist and educator. His work has been exhibited extensively both in the U.S. and internationally, and he has taught art at Hunter College, CUNY, in New York City for nearly 15 years. There, he cofounded the New Genres area, bringing together video, performance, and public interventions. Ramírez Jonas is also reimagining printmaking studies, seeing publications as a form of public art and linking their significance to a wide range of social movements. Over the last four years, he pioneered a public art studio course at Hunter to address issues specific to different kinds of public space (courtrooms, parks, rivers, among others), and to look at how artists can and have worked with the particulars of such spaces.

The Commons (2011) is an equestrian monument, unusual in that it has no rider and implies the viewer. Made of cork instead of bronze, the monument includes materials such as pushpins and notes contributed by the public that "publish" an endless number of voices. The material and implied interaction oppose the singular voice of the state, the singular identity of the hero on the horse, and the immutable inscription of public space that bronze and stone allow. The Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, N.Y. photo / provided

The Commons (2011) is an equestrian monument, unusual in that it has no rider and implies the viewer. Made of cork instead of bronze, the monument includes materials such as pushpins and notes contributed by the public that "publish" an endless number of voices. The material and implied interaction oppose the singular voice of the state, the singular identity of the hero on the horse, and the immutable inscription of public space that bronze and stone allow. The Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, N.Y. photo / provided

You are an artist and educator, how did you know you wanted to be an artist — where did it all begin?

I am not one of those artists who always knew they wanted to be one. I grew up in Honduras, a place with no art museums, few galleries, and no art program in my high school. Being an artist was not in the realm of my imagination. But I did like to make things, especially toys I knew existed in the U.S. but were not available at home.

When I went to college, I actually started off studying to be an engineer, switched to computer science, but also took enough classes for an art degree, too. At the end of my senior year, I had to decide between a job in tech or going into an M.F.A. program. Ultimately, I realized I could imagine my entire life ahead of me as a computer scientist, and I couldn't imagine my future as an artist — so, I chose art.

What were some impressions you took away from your art education — some that shaped your career as an artist or educator?

I went to Brown University for my bachelor's, which has had an open curriculum since the 60s so I could take classes in any department. That gave me a classic liberal arts education — a broad base of knowledge and analytical skills that are indispensable not just to being an artist, but a citizen. I got my master's degree at RISD. What I learned there was the opposite — very narrow and specific — for example, that art makes meaning through context, and that context is the tradition of everything that has been made before. This is in contrast to science, where new knowledge can sometimes make the old obsolete and irrelevant.

You could say that one taught me the content, and one taught me the form. What I took away from my education was that you need both.

A class field trip to Newtown Creek led by an ecologist who explained the history of the creek and the superfund clean-up of the site, ending at environmental artist George Trakas's waterfront nature walk at the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant. image / provided

A class field trip to Newtown Creek led by an ecologist who explained the history of the creek and the superfund clean-up of the site, ending at environmental artist George Trakas's waterfront nature walk at the Newtown Creek Wastewater Treatment Plant. image / provided There is a range in your chosen media — your work can be an installation, a sculpture, a video, a public space. How does your practice line up with your career as an educator? Does your career as an educator inform your practice?

My work has always manifested itself in the public sphere. And that's where I'm at now with teaching and pedagogy. How can we relate the concerns of our lives in the world outside of academia to what we are doing as artists, instructors, students? How to expand what we are doing as a department. This relationship art education could and should have to the world has directly impacted the classes I have taught. The classes I'm most interested in look at the specifics of different public spaces — a public space around a sewage plant, a cemetery, Times Square, or a museum, for example. How artists might interpret, respond to, or otherwise intervene in those spaces. Fundamental to both my practice and teaching is reconsidering notions of the public versus a public. Most recently, I've been thinking about how to reconcile public practices with studio practices through the lens of multiples, printed matter, publications, and distribution. How do we make a public?

Eternal Flame (2020-21) is made of five barbeque grills, steel, wood, concrete, fire, smoke, and park users grilling. It is a monument in the form of a five-way communal grill that imagines the fire its users kindle as both a symbolic and real eternal flame. As there is always a lit cooking flame somewhere, cooking culture itself is an eternal flame, enduring in communities for generations and over vast distances. For the duration, the Eternal Flame grills remain open for public use during open hours. Socrates Sculpture Park, Queens, N.Y. photo / provided

How does your work, or, a work take shape? Where does it start?

I was raised in the tradition I like to call the "Bermuda Triangle of art." You go out and perform an action; you document it as a photograph, video, or piece of writing; you collect a material relic or residue of the performed action. You then juggle these three: action, documentation, relic, and you try to make something. At some point, I broke away from that and started thinking about site-specificity: How do I make something that can only exist in the site it was intended for? And then, I tried to go beyond that and think about public specificity: Can I make something that can only exist for a specific group of people? Do we always have to translate work from one form to another so it can circulate beyond its intended site or audience?

So, to start, if I know the site where the work will go, I ask myself: How does the public meet art in this space? And I conform to that. The emphasis is always on a public rather than a space.

Another Day (2003), a computer-generated NTSC video sign displayed on identical monitors, was modeled after arrival and departure displays from airports and train stations. Rather than modes of transportation, Another Day tracks the sunrise of 90 cities around the world with countdowns to successive sunrises. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, N.Y. image / provided

Another Day (2003), a computer-generated NTSC video sign displayed on identical monitors, was modeled after arrival and departure displays from airports and train stations. Rather than modes of transportation, Another Day tracks the sunrise of 90 cities around the world with countdowns to successive sunrises. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, N.Y. image / providedCan you share an example?

I made a piece that tracks the sunrises of 90 cities around the world (before you could just Google that), and it took the form of three monitors that look like airport arrivals and departures displays, but the time is a countdown to the sunrise in each city in sequence. That was originally a gallery piece. But then a museum in England wanted to show it in both an exhibition and a public space. That piece, Another Day, is about waiting, so we decided to site the public presentation at a train station platform next to the monitors with train arrival and departure times. It has since traveled to other spaces of waiting — ticket lines, for example.

Participation is also important to me, but I want it to be in the form of an exchange. I don't want participation to be that you press a button and something happens. But in the public realm, exchange can become a bit of a formal problem: On an everyday basis, what do we have to exchange with? So, I think about the things we carry around in and on our bodies, for example, a wallet, money, phone, ID, fingerprint, name, or voice and speech. Each of these can generate an exchange or social interaction that can be used as the building block for a piece. This practical and observational perspective is where my work often begins; but then a larger concept arises from there. For example, what does it mean to promise something, what makes our word "good," how do we lie?

What often surfaces is that often, very powerful politics reside in the quotidian.

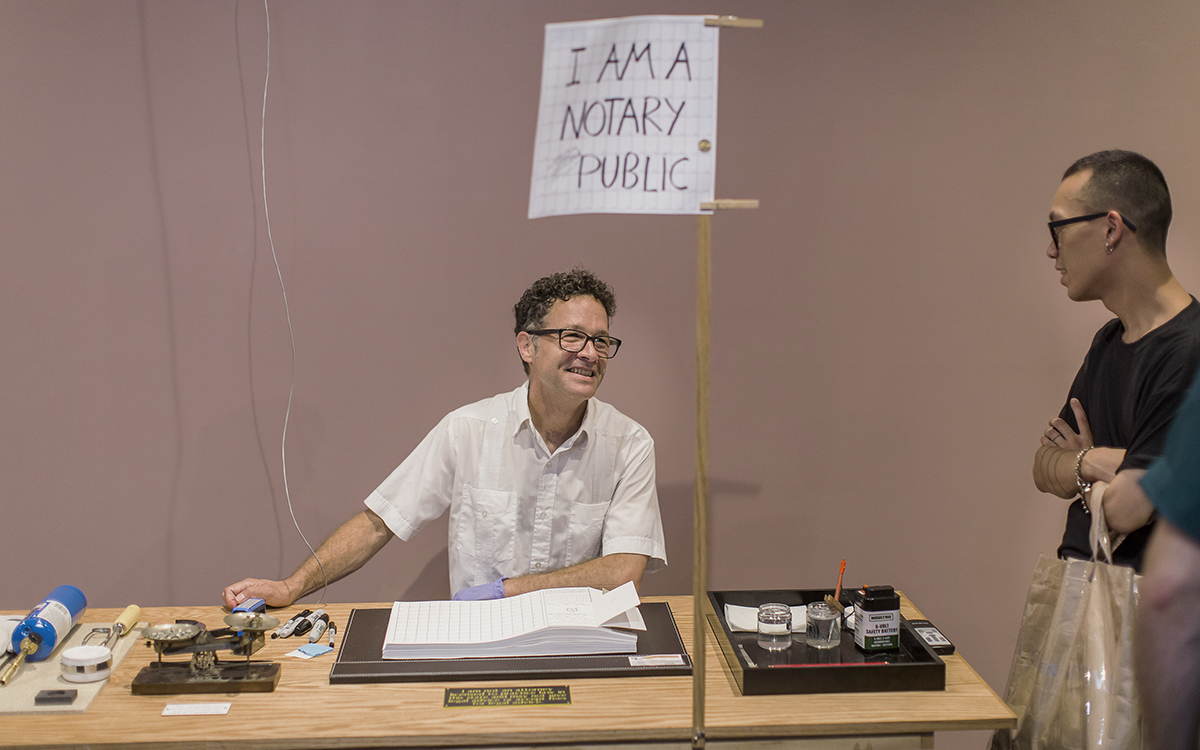

Alternative Facts (2017) consists of lies and spare change supplied by the public, a notary public seal and stamp, a signature, ledger, and leather desk pad, as well as a gold electroplating kit, scale, pyrite, paper, a gold melting and casting kit, paper, and a folding table. The piece turns lies and fantasies into ostensibly truthful public documents. The first untruth designates the facilitator, often the artist himself, as a notary. Each subsequent certification process yields two documents, one for the viewer to keep and another to be collected in the installation. The cost of this legal transformation requires payment of a gold coin, which the facilitator will assist in creating by chemically altering a visitors' spare change. The New Museum, New York, N.Y. image / provided

Alternative Facts (2017) consists of lies and spare change supplied by the public, a notary public seal and stamp, a signature, ledger, and leather desk pad, as well as a gold electroplating kit, scale, pyrite, paper, a gold melting and casting kit, paper, and a folding table. The piece turns lies and fantasies into ostensibly truthful public documents. The first untruth designates the facilitator, often the artist himself, as a notary. Each subsequent certification process yields two documents, one for the viewer to keep and another to be collected in the installation. The cost of this legal transformation requires payment of a gold coin, which the facilitator will assist in creating by chemically altering a visitors' spare change. The New Museum, New York, N.Y. image / provided

To what degree do you think of your work as politically and/or socially engaged? How is this important?

It wasn't until quite a bit after I got started that I became known as a politically engaged artist interested in social practice. There are artists who make work about politics — institutional critique, for example, and they are indispensable. It is very evident where the politics are in their work. I try to always think about who I am addressing and what language I am using for this address. For me, there is nothing more political than to make work that is interesting, legible, and accessible to a broader and more diverse public than the one that is currently most welcome in our museums and galleries.

This is what is exciting for me about being at AAP, where the art department is housed with architecture and planning rather than art history, which is far more common. I feel there might be more of a political alignment because all three practices are spatial, publicly oriented, and engaged with the world, not just ideas.

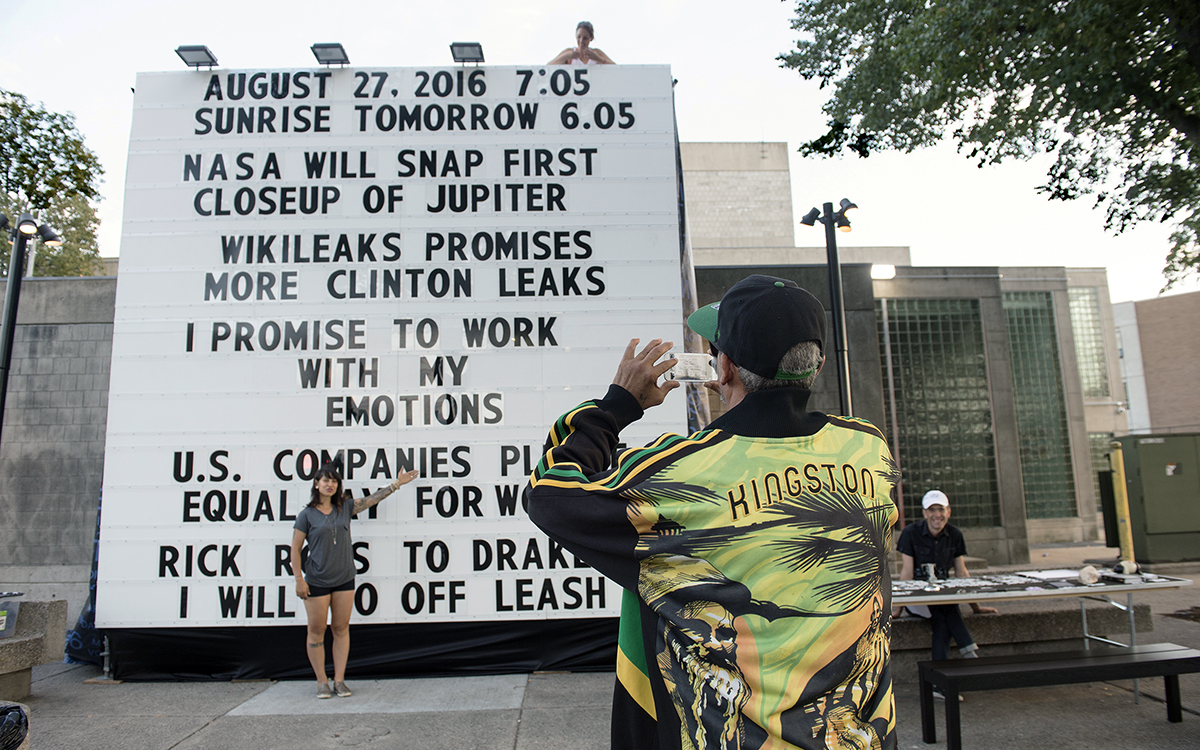

Public Trust (2016) is comprised of a 16-foot marquee, sacred and civic texts, oaths, promises from private individuals, promises from public figures, graphite, and paper, asking: How serious are the promises we make to one another, the vows we take, or the pledges made by our civic leaders? Participants declare and are asked to give their word in a way that is consistent with their beliefs, such as swearing on a sacred text. That promise is then published on a 16' x 16' marquee board seen in context with promises made by politicians, scientists, economists, and weather forecasters — all chosen daily from headline news. image / provided

In your view, has how artists practice fundamentally changed in the context of our particular moment — of environmental crisis; of movements for greater equity and justice; of evolving and emerging technologies?

We're in a very difficult moment as cultural producers. There is an arc around identity politics, and I mean that term in a good way, that begins with a narrow canon breaking open because of postmodernism and allowing more self-representative voices into the practice and discourse. The result is a multiplicity of discourses rather than a unified discourse — also a good thing — but we haven't quite figured out how to parse how this works. We're still trying to adjudicate. To decide who speaks and when, who can speak for whom, to come up with new ways to measure "quality," or, to let go of that concept entirely — and we have yet to see the effects of these unresolved conflicts on the imagination.

As a result, it seems younger artists are moving in two seemingly irreconcilable directions. One is inward-looking, into personal subjectivity through the lens of ever more precise identities. The other is outward-looking, with an interest in systemic and structural questions. I am very excited to see that this upcoming generation does not necessarily see a contradiction here.

How do you think the changed and changing world can inspire the next generation of artists — what can educators do here and now? What can students do?

There is a pedagogical opportunity here. The problems of the school are the problems of the world. We address the need for diversity, equity and inclusion, scarcity of resources, capitalism encroaching on everything, the legacy of colonialism, etc. We are not other, separated from reality. What if as educators and students we used the school as a space for rehearsal as well as a space of real consequence? What if we all worked with generosity and patience for each other, on the challenges of deploying the creativity of artists, architects, and planners toward solutions to these problems?

Key to the City (2010) consists of people, 24,000 keys, 24 sites, 155 collaborators, and the mayor. In this case, the key to the city is both a symbol and an award. It is traditionally given to a hero or any other worthwhile non-citizen symbolizing that they are now "one of us" who has free entrance to the city. This new key to the city is awarded among a public that grants each other the key to the city for private reasons that exist outside of history. Instead of receiving the award for winning the World Series, for example, we are recognized for delivering all the letters along our route. One at a time, person to person, all the time, thousands of keys are bestowed by thousands of people, thousands of citizens, for thousands of reasons that deserve to be recognized. Times Square, New York, N.Y. images / provided

Key to the City (2010) consists of people, 24,000 keys, 24 sites, 155 collaborators, and the mayor. In this case, the key to the city is both a symbol and an award. It is traditionally given to a hero or any other worthwhile non-citizen symbolizing that they are now "one of us" who has free entrance to the city. This new key to the city is awarded among a public that grants each other the key to the city for private reasons that exist outside of history. Instead of receiving the award for winning the World Series, for example, we are recognized for delivering all the letters along our route. One at a time, person to person, all the time, thousands of keys are bestowed by thousands of people, thousands of citizens, for thousands of reasons that deserve to be recognized. Times Square, New York, N.Y. images / provided

What are you working on currently? Or, what's next?

I'm working on a very large project, Key to the City, the first iteration was made 10 or so years ago in New York City. I'm adapting it to a big industrial city that I can't yet name, but I'm excited to imagine what a key to that city would look like. It will be a multiple, available by the thousands to the public, and each key will open sites all over the city. The challenge is how to address this particular city's complicated relationship to empire and industrialization. The project will not only ask: What is public space? But, also tell the story of the city's history and its relation to different parts of the world through the movement of goods and peoples.

Simultaneously, I'm working on a studio piece that extends the work I've done on reimagining monuments — statue, obelisk, fountain, for example. Specifically, I am trying to re-formulate what a mural can be. Often in my public art, I try to make it function at two scales — one is intimate, the other one is broadcast. So, I am trying to make the mural also exist as a book you can hold in your hands. Again, I am thinking about whether publication can bridge the gap between public and private practices. To tell you the truth, I have no idea how it will turn out. There is a very good chance of failure.