Who Is Don Greenberg, and Why Is He Pixelated?

In his five decades of teaching and research, Greenberg has won many prestigious computer graphics awards. Throughout a career spanning the immense growth of computing power, he has focused on the skills architecture students will need to keep pace.

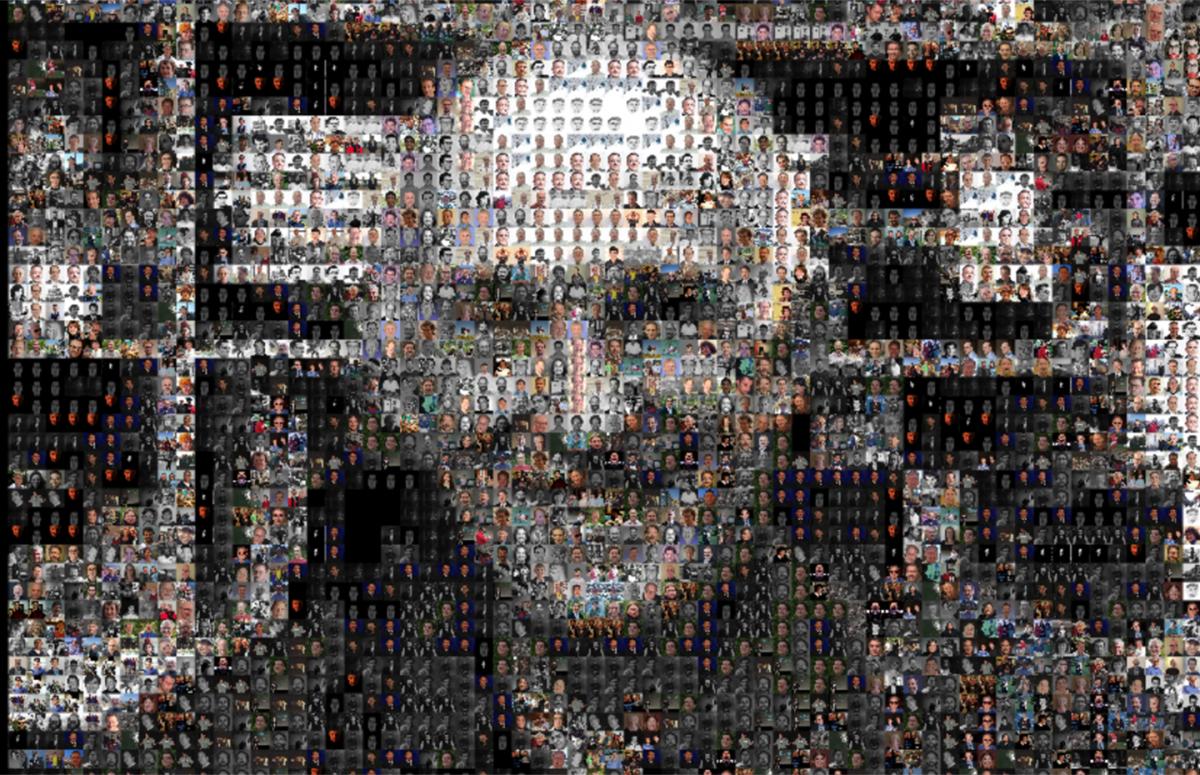

Detail from an animated, visual representation of Greenberg's former students developed by Autodesk software engineer Eric Haines (M.Arch. '86) underscores Greenberg's impact on the careers of hundreds of alumni.

Detail from an animated, visual representation of Greenberg's former students developed by Autodesk software engineer Eric Haines (M.Arch. '86) underscores Greenberg's impact on the careers of hundreds of alumni.

It is August 29, 2019, and Greenberg — the Jacob Gould Schurman Professor of Computer Graphics at Cornell University in the Department of Architecture, Computer Science, and the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business — has just returned from a yearlong sabbatical leave where he worked at Disney Research-Zurich, taught at the Swiss ETH, researched at Nvidia and visited Stanford, as well as UC–Berkeley where he worked on foveated rendering with computer scientists, perception psychologists, and neuroscientists.

He stands in front of an audience of undergraduates in AAP's Abby and Howard Milstein Auditorium for the first session of Visual Imaging in the Electronic Age, a fall semester survey and introduction to computer graphics class open to students enrolled in architecture, computer science, or engineering. Greenberg has taught the class nearly every year since the early 1980s.

"There is no simple book that covers all these topics, that covers both sides of the brain," he tells the audience. "I'm no longer qualified to teach the programming details but I know enough about many applications and hardware and coming software innovations to teach a first- or second-year survey class."

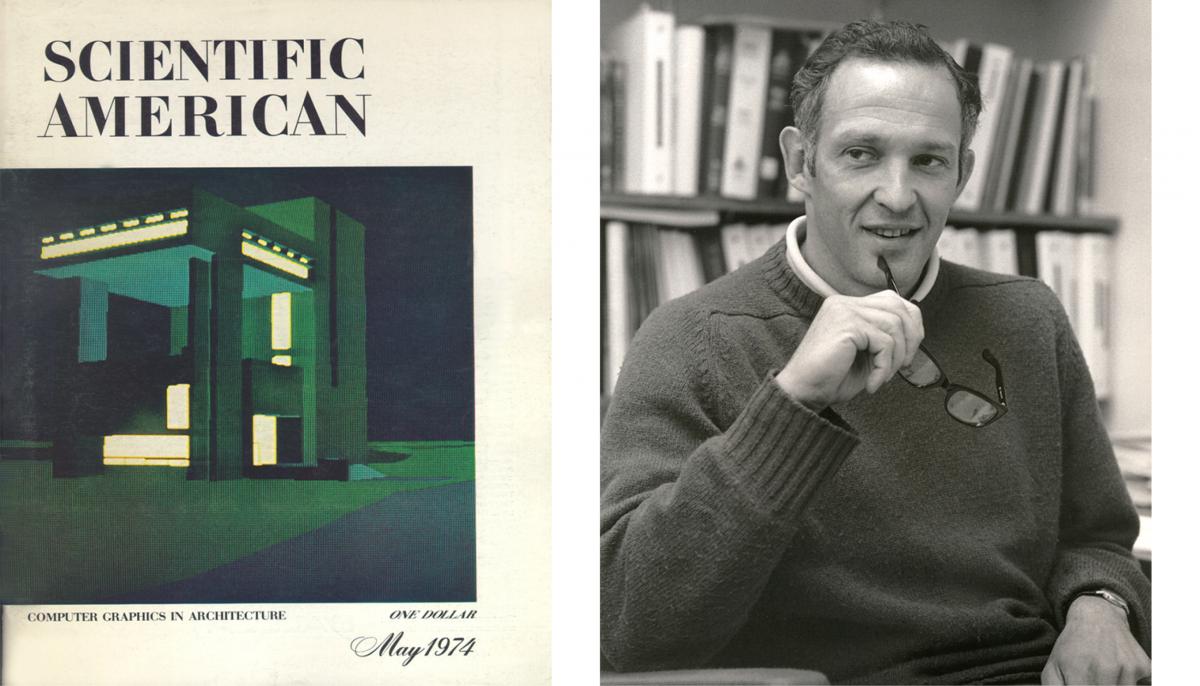

This is a surprising admission from someone whose career has spanned the computer graphics revolution from its genesis in the 1960s. Speaking into a hands-free mic, Greenberg moves around the podium, smiling, hands lifted. Projected above him is a simple computer-generated 3D perspective rendering of the I.M. Pei-designed Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art in twilight. He talks about how stunningly far the field has moved since he and a few architecture students created some of the first computer-simulated images and how this rendition graced the May 1974 cover of Scientific American.

Left: May 1974, a computer-generated model of the Herbert Johnson Museum featured on the cover of Scientific American. Right: Don Greenberg,

Left: May 1974, a computer-generated model of the Herbert Johnson Museum featured on the cover of Scientific American. Right: Don Greenberg,professor of architecture (ARCH) and computer graphics (COMS), 1977. Russell Hamilton / UREL

A Technique in Search of a Problem

Some of the first computer design simulations were done at Cornell in the early 1960s, but, according to Greenberg, at the time it was believed that computers would never be used to plan or design buildings.

"We were a technique in search of a problem," he says. For example, deriving methods of capturing a building’s geometry with photographs shot from multiple locations, and using them to merge new designs with existing structures.

Projected images rush forward as Greenberg describes the progression from the first available mini-computer workstations to the supercomputers of the 1980s, from the early iPhones to the Nvidia graphics cards of today, and beyond. Greenberg sees the enormous acceleration of computer power as having enabled the unexpected.

"Who would have thought that our early work on 2D cell animation with Hanna-Barbera in the 1970s would evolve to Pixar's photorealistic 3D creation of Toy Story two decades later, or the 'filming' of The Lion King in VR today," Greenberg muses. "The change in computer power will allow a new way of storytelling in VR. The 10 hours of computation for a single frame in Toy Story will have to be completed in 11 milliseconds."

Greenberg's audience is rapt. After his abridged history of computer graphics, the astonishing pace of computing power and its limits, he turns to the future. He explains a law of exponential growth based on Intel cofounder Gordon E. Moore's prediction that the number of transistors on a microchip doubles every year, while the cost of computers is halved. It is a pace that cannot continue indefinitely, and Greenberg says the industry is still driving the chip technology research but will reach economic barriers before the technology barriers.

"There is no way you can fathom what's next with that kind of exponential increase in computing power. In the next three years, as much computing power will be made as has been available in all time previously," he says, adding, "and we need to teach ethics, too, to understand how the technology is being used."

Greenberg's cross-disciplinary background and the ongoing work he does in his lab afford opportunities to understand the broader contexts and implications of computing, though he maintains that there remains much work to be done to exchange knowledge and enhance the discourse as it applies to the disciplines of architecture, engineering, and computer science.

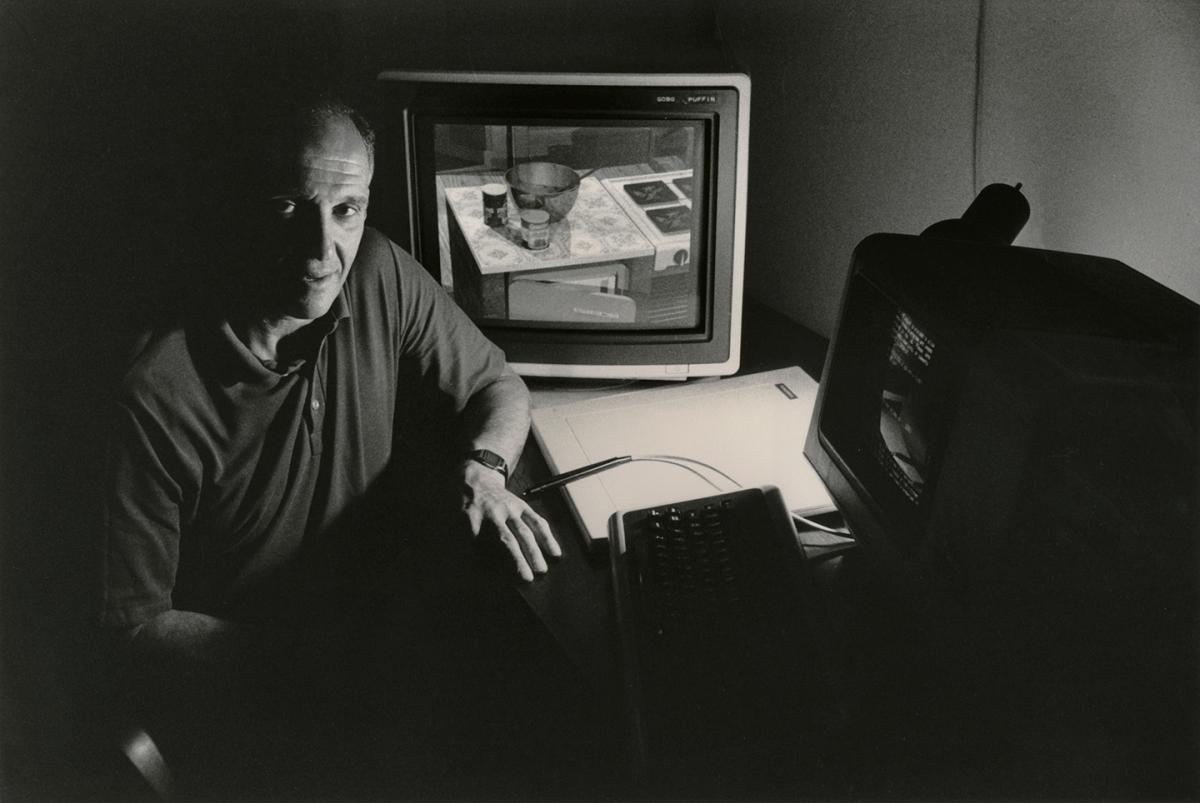

Don Greenberg, professor of architecture (ARCH) and computer graphics (COMS), in the lab in 1987. Claude Levet / UREL

Don Greenberg, professor of architecture (ARCH) and computer graphics (COMS), in the lab in 1987. Claude Levet / UREL

The Work of a Lifetime

After studying architecture and engineering at Cornell and Columbia University, Greenberg served as a consulting engineer and was involved with the design of numerous building projects from 1960 to 1965, including the St. Louis Arch, New York State Theater of the Dance at Lincoln Center, and Madison Square Garden. Specializing in computer-aided design, he joined the Cornell faculty in 1968 with a joint appointment in the departments of architecture and structural engineering and soonafter founded the interdisciplinary Program of Computer Graphics with the support of then President Dale Corson.

At AAP, Greenberg's teaching has covered computer-aided design in architecture as well as computer animation in the Department of Art, and he has simultaneously taught computer graphics courses in computer science and technology strategy in the Cornell SC Johnson College of Business. Among many achievements, Greenberg received the 1987 ACM SIGGRAPH Steven A. Coons Award for Outstanding Creative Contributions to Computer Graphics, its highest honor, and the 1989 NCGA Academic Award, the highest educational award given by the National Computer Graphics Association. He is a member of the National Academy of Engineering; Founding Fellow, American Institute of Medical and Biological Engineering; Fellow, Association for Computer Machinery; Fellow, American Association for the Advancement of Science; and the founding director of the 11-year National Science and Technology Center for Computer Graphics and Scientific Visualization.

Recently, ACM SIGGRAPH honored Greenberg with the 2020 Distinguished Educator Award for outstanding pedagogical contributions to computer graphics and interactive techniques. The award recognizes his impact on research and practice of education; cumulative contributions to the field both directly and through the leadership of others; innovation in education; and influence on the work of others and educators who are making a difference as innovators or pioneers in their respective disciplines. Greenberg is only the second recipient to be selected for this award.

In recognition of his contribution to the field, Greenberg was interviewed for the 21st International VFX Computer Graphics Conference (VIEW) in Turin Italy on October 20. Recordings of any of the conference events will be available online from November 1 through December 31.

Also recently, Greenberg's early animation work was selected for inclusion in a large-scale exhibition on the computer's influence on the architecture discipline from the 1960s to the present. "The Architecture Machine. The Role of Computers in Architecture" opened October 13 at Architekturmuseum of the Technical University of Munich. Cornell in Perspective (USA, 1969-1972), the first large-scale rendered fly-through of urban space, was digitized for the show from the original 16 mm film.

The film largely demonstrates Greenberg's description of the early days of computer graphics when pioneers of new techniques were very much "in search of a problem," and, when new techniques were taken up to solve problems as diverse as medical stents for brain aneurysms and aid in the search for the ivory-billed woodpecker.

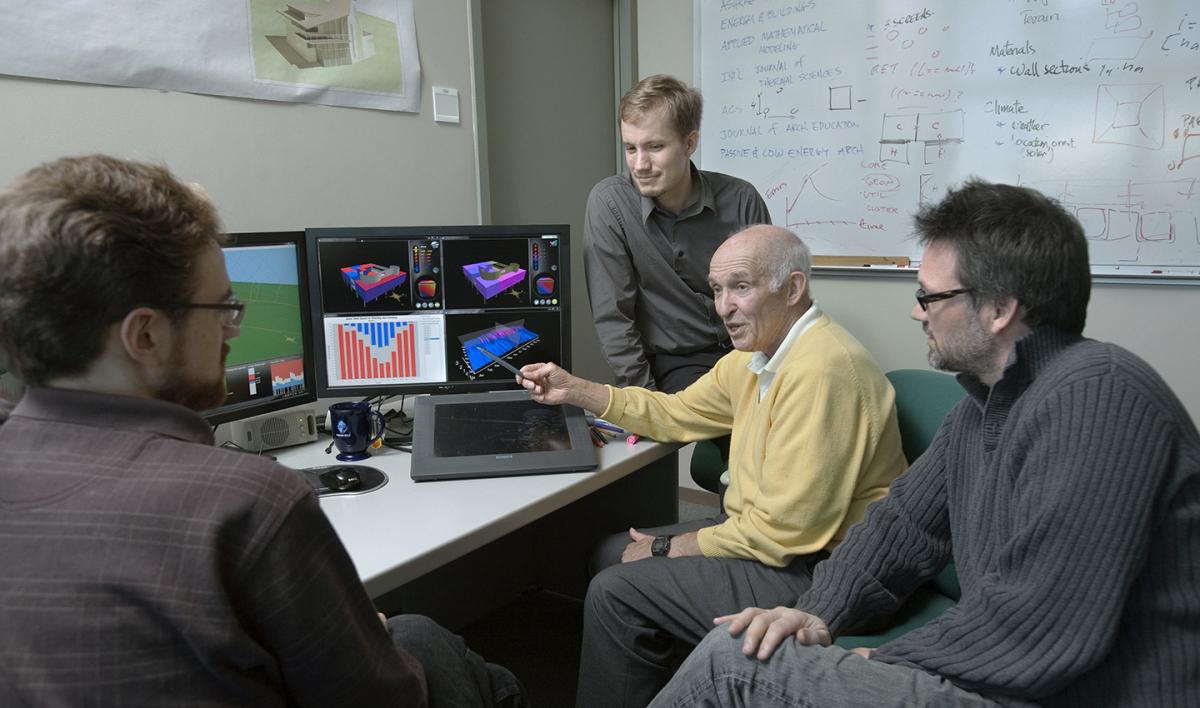

Greenberg leading a multidisciplinary research group funded by the U.S. Department of Energy that linked the departments of Computer Science, Architecture, and Mechanical Engineering. The group included the late Kevin Pratt (right), an assistant professor in architecture who worked closely with Greenberg. Jason Koski / UREL

Greenberg leading a multidisciplinary research group funded by the U.S. Department of Energy that linked the departments of Computer Science, Architecture, and Mechanical Engineering. The group included the late Kevin Pratt (right), an assistant professor in architecture who worked closely with Greenberg. Jason Koski / URELProfessor Greenberg is not only a teacher but first and foremost a curious student whose questioning and cross-disciplinary thinking will drive the next generation of change within architecture and traditional design workflow. Like many students before me, he has been the most influential professor during my time at Cornell, not because he taught us facts, but because of his unique ability to teach us to ask, "what if?"

Aishwarya Sreenivas (B.Arch. '21)

History, Hockey, and the Future

In a recent conversation, Greenberg talked about his current concerns and how he may leave some of the legacy of the Program of Computer Graphics to the Department of Architecture. Many of his students have been highly successful, inspiring as collaborators, and have helped to shape a new industry. He only wishes more of his graduate students had become practitioners or teachers in architecture.

"The Department of Architecture is my original academic home and the people I have interacted with for the longest time," Greenberg says, adding that the first graphics laboratory and CAD design studio were located in AAP's Rand Hall. "One of my challenges for the future is how to create a new digital platform with immense computational power and put it into the hands of creative architecture students without impeding or constraining their early-stage design creativity," he says.

Based on a design studio he taught two years ago to architecture and computer science students at Cornell Tech, Greenberg designed a two-semester course for the same cohort that would introduce the work he is doing with Nvidia and other industry leaders. Originally scheduled for this year, the class has been postponed due to the pandemic.

"The challenge now is tracking where the eye sees, how to measure the human visual system, how to speed up the computations and discover where a user is both looking and where they will look next," he says, referring to a convergence of discussions with different disciplines including perception psychologists, ophthalmologists, neuroscientists, and computer scientists, as well as from Google, Microsoft, and gaming culture.

Sensitive to the important role of the history of architecture, Greenberg says that perhaps the lessons of the past are even more important to young students today during the Coronavirus pandemic, and, as the built environment and sustainability, public health, infrastructure, existing stock, and equity are all under scrutiny.

"Should we not know the significant design influences of the past and ask why they were important while we learn the new technologies of the future?" he asks, going on to quote Louise Glück, winner of the 2020 Nobel Prize in Literature: "'We look at the world once, in childhood. The rest is memory.'"

Ever the optimist, Greenberg reflects hopefully on both the past and future, reminding us that after the Bubonic Plague of the Middle Ages in Europe, the devastation of that era was followed by the Italian Renaissance.

Back in Milstein Auditorium on that August day in 2019, the end of the hour arrives.

Greenberg returns to the puzzle of perception and advises to "remember what hockey champ Wayne Gretzky said — 'Look where the puck will be!'"

He asks that his students, the disciplines, and the university look there, too.