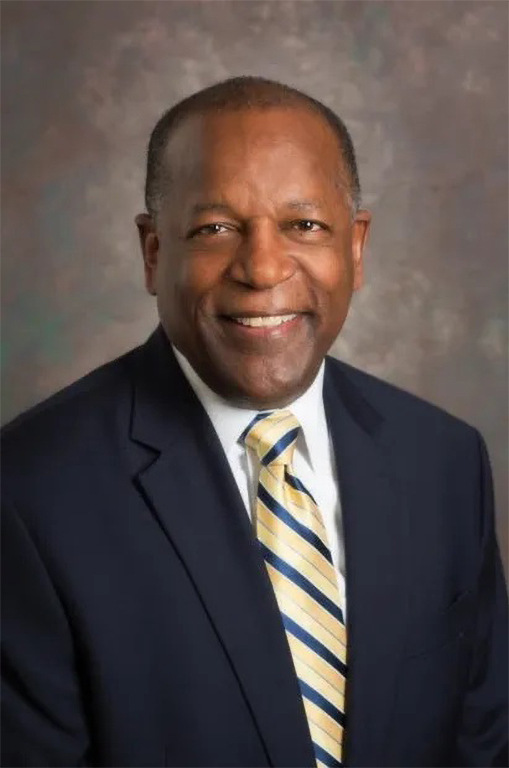

When H. Alan Brangman (B.Arch. ’75) talks about architecture, he doesn’t focus on design, construction, or engineering, although he certainly acknowledges their importance. Instead, he emphasizes “the learning process of architecture, which is about teaching people to participate.”

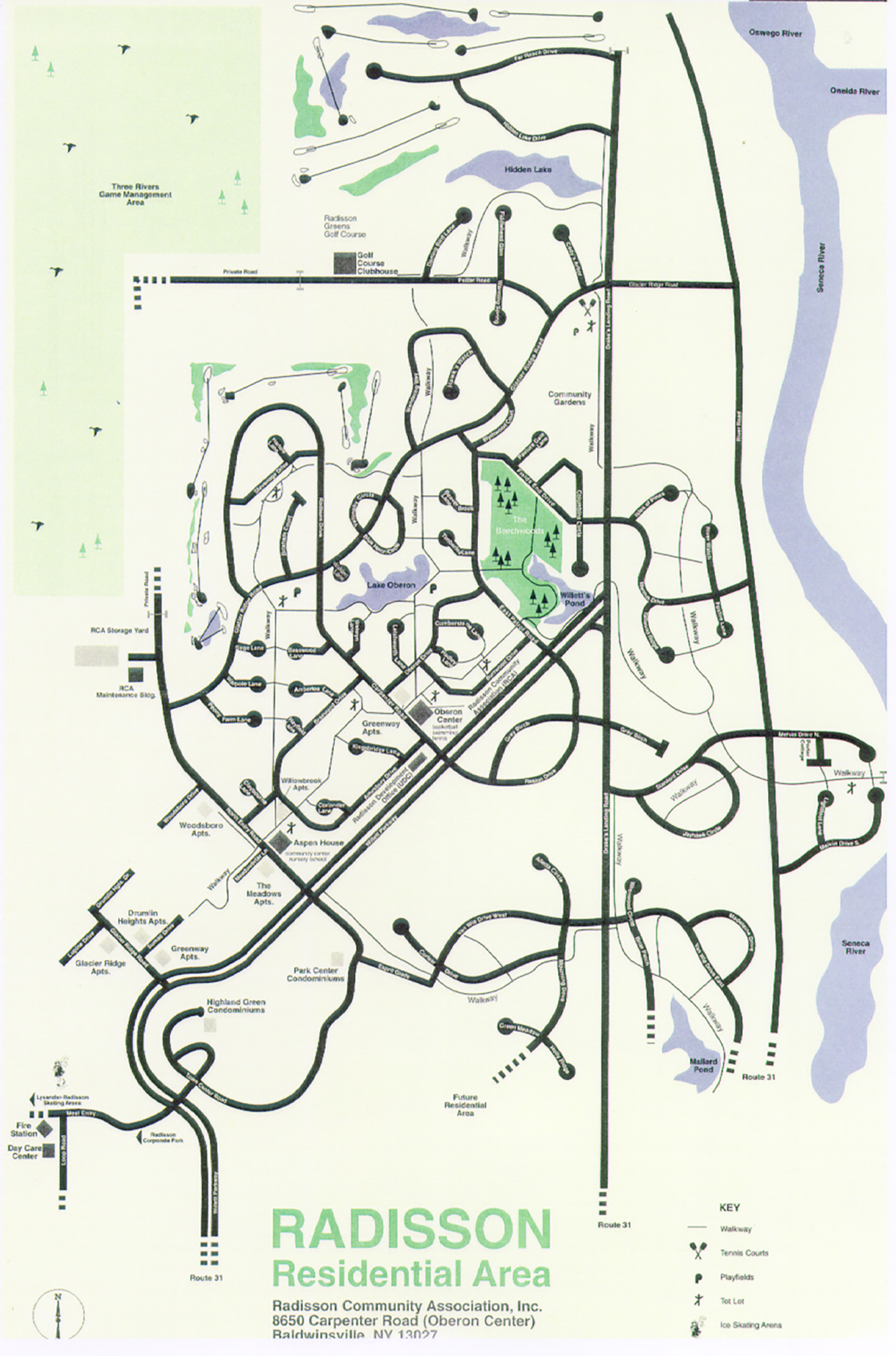

In design and architecture firms, on college campuses, in government agencies, and even as mayor of Falls Church, Virginia, Brangman has espoused and delivered on that philosophy — bringing teams together and, when obstacles arose, helping people realize “there’s always another solution.”

“In architecture, you’re taught to change, change, and change again until you arrive at the best solution,” he says. “There’s no such thing as getting stuck.”

Brangman applied that philosophy early in his career after being told it was unlikely he’d advance because the firm where he worked already had a Black associate partner. The conversation “opened my eyes to the political reality for minorities in architecture at the time,” Brangman recalls. “Then it dawned on me that there is a much larger world out there — that I could become more of a ‘master builder.’ I could control the design and assemble the teams and skills to build places where people can live, work, and play.”

Over the next four decades, that’s exactly what he did.

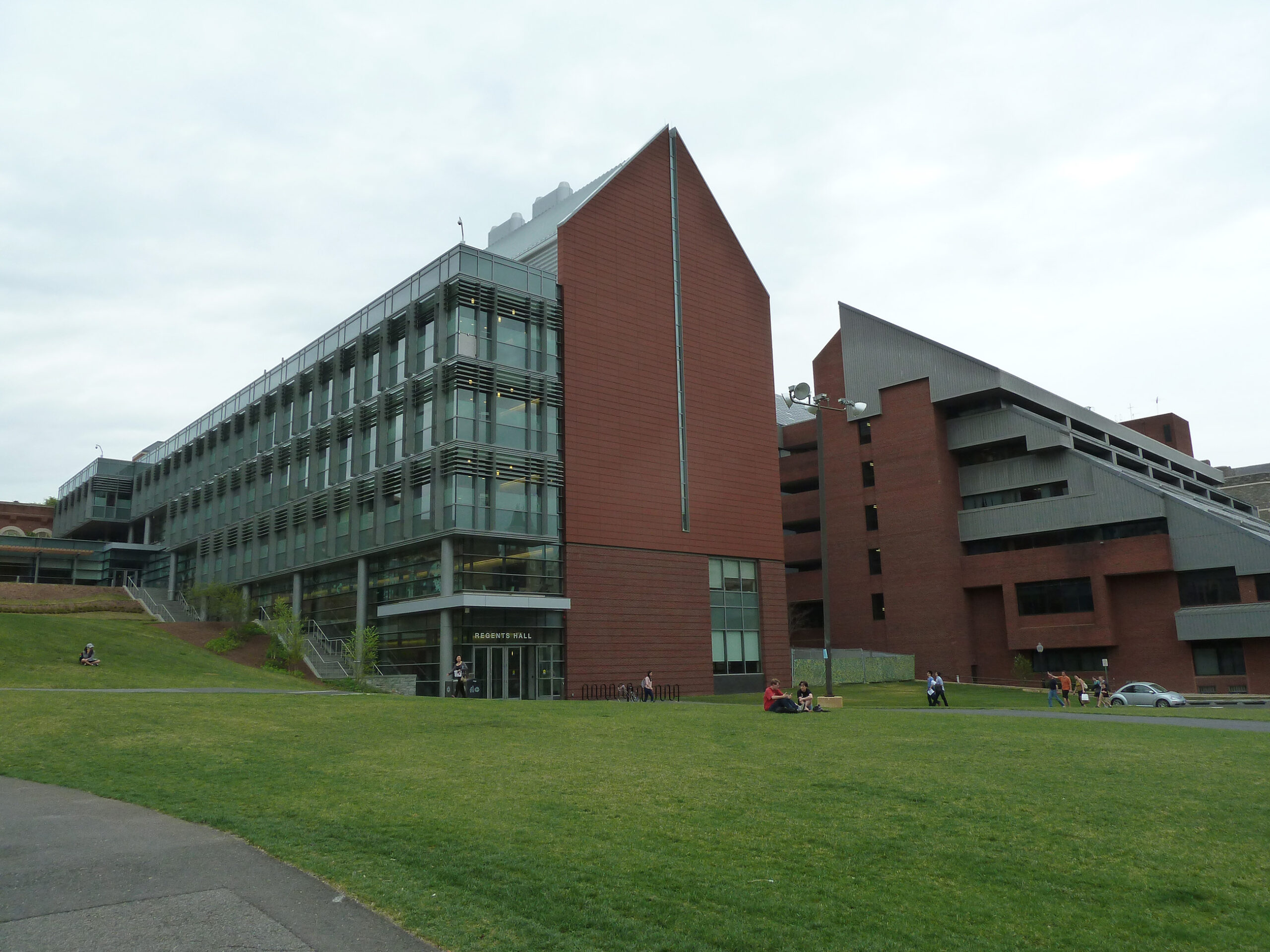

As director of downtown development for The Oliver Carr Company (now Carr Companies) in Washington, DC, Brangman helped transform the capital city by overseeing the development of more than 5.8 million square feet of office and retail properties. At Georgetown University, Howard University, and the University of Delaware, he helped create environments where students, faculty, and staff flourished. He also honed his skill set by earning an Executive Master’s in Leadership degree from Georgetown.

As deputy director of the Design Arts Program at the National Endowment of the Arts, Brangman extended his influence, shaping and advancing design projects across the U.S. — reaching beyond architecture and landscape architecture to urban design and planning, historic preservation, industrial and product design, graphic design, interior design, and costume and fashion design. Closer to home, in the City of Falls Church, Virginia, he shared his expertise as a member of the Planning Commission and City Council and as mayor.

Brangman entered politics to help improve zoning and planning policies in his community. His tenure was relatively brief by choice: four years on the council, including two as mayor. Although now retired from public life, Brangman remains engaged in local issues. He also is not shy about taking a stand. He has made local news for participating in a panel discussion on affordable housing, endorsing the removal of names of slave-owning founders from public buildings, and supporting protests in response to George Floyd’s death while in police custody.

In virtually every instance, the master builder’s actions reflect the lessons he learned as an architecture student at Cornell.

In architecture, you’re taught to change, change, and change again until you arrive at the best solution.

Brangman had wanted to be an architect since seventh grade, when he gave a Career Day presentation on the profession. He was on track to enroll in an architecture program at an Ivy League institution until, he admits, he succumbed to senioritis as a high school student. He started his college years at the University of New Hampshire, majoring in engineering while working on an architecture portfolio on the side. As a sophomore, he took an elective class in architecture, showed his portfolio to the professor, and doors opened.

The professor reached out to a former colleague — Henry Richardson, a professor in Cornell’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning — and arranged an interview. Brangman remembers leaving Durham, New Hampshire, at 2 a.m. for the 400-mile drive to Ithaca and his 9 a.m. appointment. The interview went well, and Brangman started at Cornell that fall, attending classes year-round to make up for lost time and to graduate on time. Richardson became and remained a mentor to Brangman throughout his time at Cornell.

Two other professors also stand out. From Donald Greenberg, then a professor in structural engineering, Brangman came to appreciate how structure and aesthetics work hand in hand. From the late Colin Rowe, the Andrew Dickson White Professor of Architecture and head of Cornell’s Urban Design Studio, Brangman learned that good architectural design requires looking beyond individual buildings to their impact on the larger landscape. That viewpoint is reflected in Brangman’s work on college campuses and in downtown Washington, DC.

Brangman’s Cornell education influenced his life in other ways, as well. He grew up in Fairfield County, Connecticut, an area that was considerably more diverse than Ithaca, but at AAP, he was one of only a handful of minority students. He remembers being called into the dean’s office after participating in a student takeover of the administration building to protest proposed changes to the Committee on Special Educational Projects (COSEP). The committee was established in 1965 to increase representation of Black students at Cornell and provide support services for them. COSEP’s mission was later broadened to include students from other minority populations and those who are economically or socially disadvantaged.

The dean suggested that, with just one year of school left, Brangman should focus on his studies.

He views that conversation as a reminder that “the real world” — the weak job market for architects during the 1970s recession and the limited opportunities for Black professionals — “was about to hit me in the face,” and he needed to be ready.

“Even the things that were difficult were learning experiences,” Brangman recalls. “Given what was happening in the U.S. at the time, those experiences also were good preparation for life outside Cornell. I met a lot of people from a lot of different backgrounds and a lot of different places, and we learned to relate to one another.”

Cornell’s reputation as one of America’s top architecture schools has also served Brangman well. To this day, he enjoys being asked that age-old question, “Where did you go to school?”

“I say, ‘Cornell University,’ and I watch their eyes widen,” he says. “I know I’ve enjoyed opportunities that I wouldn’t have had if I’d gone to a different school. I look back on my time at Cornell, and I wouldn’t change a thing.”

Projects

Click to view project images full screen.