As a child, David Benn (B.Arch. ’74) took his first step toward a career in architecture when he built a tree house with his grandfather, who was a skilled builder. Benn pursued this career interest in high school by taking classes in art and drafting, as well as talking to architects about architecture schools. One architect recommended Cornell’s College of Architecture, Art, and Planning. Further influenced by a family drive through gorgeous Ithaca, Benn knew by his third year in high school which college he wanted to attend. “Cornell was always at the top of my list,” he said.

At Cornell, Benn learned about architectural design and the importance of presenting his work well. He also took several classes on the history of architecture to feed his curiosity about how contemporary designs related to architecture of the past. “I always liked the idea that architecture was part of a context,” Benn said.

After graduating in 1974, Benn moved to London to look for work. He landed a job with the London Borough of Enfield to work on housing, but a work permit was required before he could start. While waiting, he traveled around Europe, starting in Finland, where he explored works by architect Alvar Aalto. In January 1975, Benn started his new job and worked there for a year and a half.

He then returned to the U.S. and settled in New York City, where he obtained his license to practice architecture. He worked for several architectural firms, gaining experience with different types of buildings. In 1981, Benn moved to Ithaca to take a job with Levatich & Hoffman; soon after, he began teaching second-year design studios as an adjunct professor at Cornell. His thesis advisors Charles Pearman and John Shaw continued as mentors through teaching and beyond.

During these early years in his career, Benn explored different design aesthetics as he developed his own style. He was interested in creating friendly, accessible designs that used more color and materials without being too literal to stylistic references. Benn was also developing interests in community preservation. He thought that architects should help set the framework for development, so he started creating community and campus master plans.

After four years in Ithaca, Benn moved to Baltimore to join Cho Wilks & Associates, a firm started by two of his classmates at Cornell — Diane Cho, whom Benn later married, and Barbara Wilks. Only four years after its inception in 1979, the firm had grown and was receiving an influx of projects. He has remained with the firm ever since.

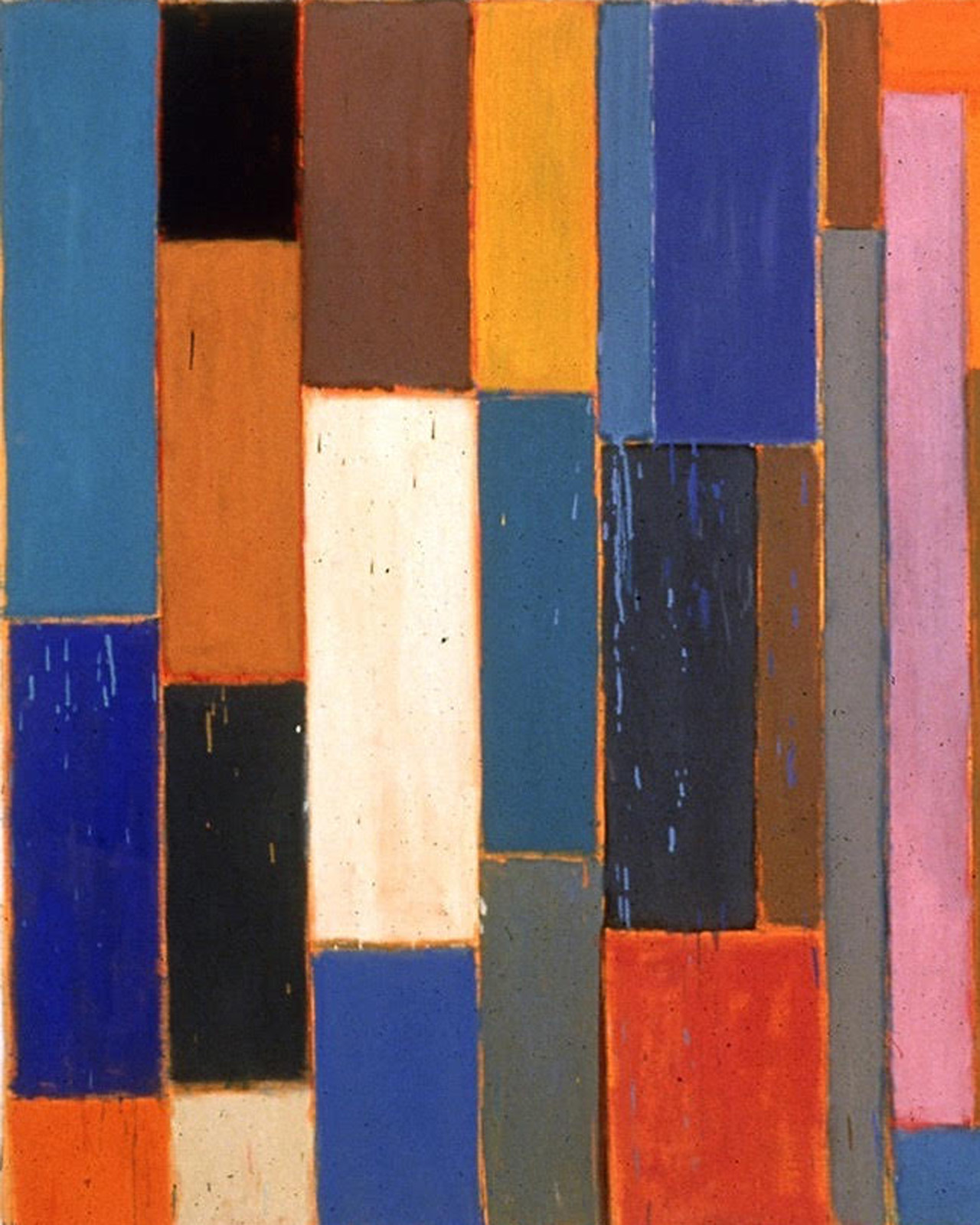

One of Benn’s early projects, the Tindeco Wharf redevelopment, transformed a vacant historic factory on Baltimore’s harbor into an active multipurpose community. The transformed site housed a residential building with 240 luxury apartments, a health club, a swimming pool, office space, a restaurant, and a parking garage. Completed in 1987, Tindeco helped to revitalize the adjoining neighborhood and better connected the community to the waterfront, which has substantially transformed the whole area. The firm won more than seven historic and architectural awards for the project.

Benn helped to expand the firm’s work into education and community projects, often combining the new with renovation. Cho Wilks Benn’s campus and community master plans linked open space with current and proposed buildings to create and strengthen special places.

I always liked the idea that architecture was part of a context.

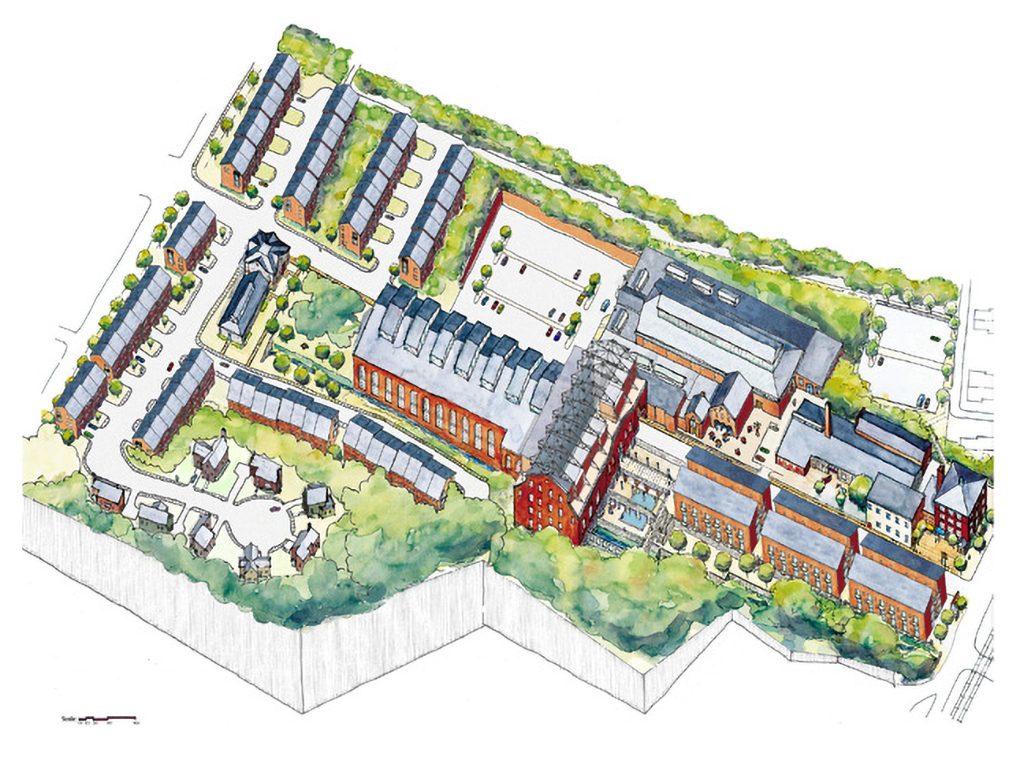

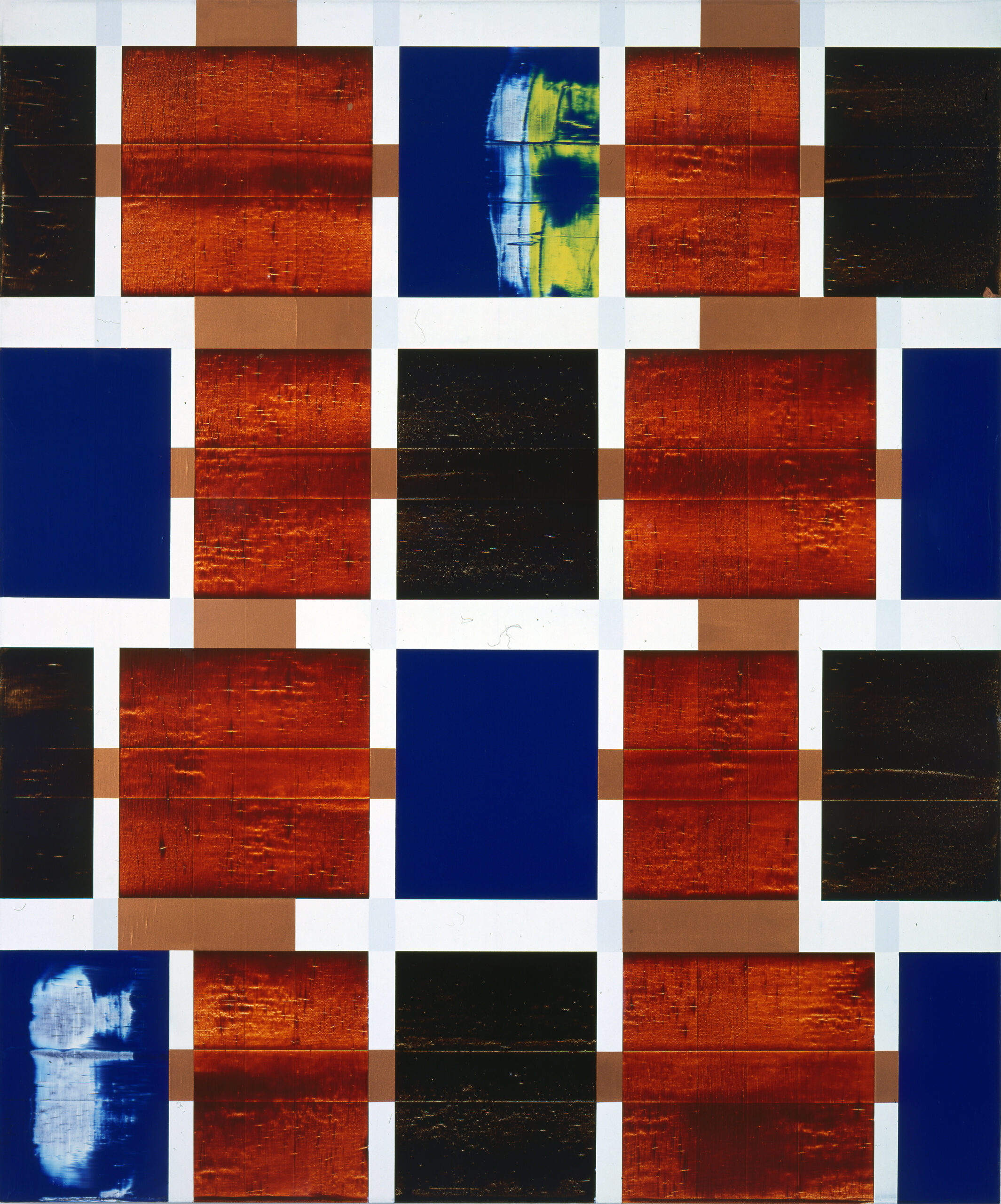

In the early 2000s, the recently renamed Cho Benn Holback firm renovated another historic industrial site. Once a former metalwork complex, Baltimore’s Clipper Mill site had been destroyed by a fire in 1995. Charged with renovating five historic buildings, the firm turned one burned warehouse into condominiums and another into apartments. It transformed huge warehouse spaces into places for artists and craftspeople to work. Another warehouse space became an assembly building that included 10,000 square feet of office space, 36 loft apartments, and an open-air courtyard. The project also included a newly constructed apartment building with a parking garage.

Cho Benn Holback transformed the site into commercial and residential spaces while still evoking the location’s industrial past. The construction itself further reinforced the character of the place by reusing the old buildings and integrating ruins of walls and artifacts such as cast iron columns, gears, and grinding wheels. Once a mostly vacant ruin, Clipper Mill became a unique village that even has a trail running through a building courtyard to connect the site to an adjoining greenway. The project later received many awards for revitalizing the neighborhood.

Cho Benn Holback’s strong reputation and work in a variety of sectors helped it survive multiple recessions. “But we were always beating our head against the wall. It never was an easy thing,” Benn said. By 2017, the partners were nearing the age of retirement and worrying about the firm’s continuity. It had always been a small firm of 35 staff members at most, but in recent years, the managing partners found it increasingly difficult to compete with the marketing budgets, competitive fees, and specialists staffed at large firms. To ensure the firm’s future, the partners sold Cho Benn Holback to Quinn Evans, a firm that had similar goals and was looking to grow its presence across the U.S. “They were buying the firm knowing that it had a great reputation and strong areas that they could build on,” Benn said.

Currently, Benn works part time as a partner at Quinn Evans. In his latest project, he is creating a master plan for a Catholic church in Howard County, Maryland. The project feeds his appetite for variety and new challenges. “We’re trying to do it in a way that allows the land to still be largely agricultural, where the building can fit into the landscape and allow for future growth,” Benn said. “We’re not just plopping the building out there.”

For many years, he carried his interests in revitalization and preservation into volunteer work with urban design projects in Baltimore. A lot of existing buildings and warehouses near the waterfront became threatened as the land’s value increased, Benn said. He volunteered for preservation projects meant to retain the waterfront’s industrial character and served as the chair of the Baltimore Urban Design Committee, of which he is still a member.

As of early 2021, Benn was volunteering to garner support for a Rails to Trails project that is developing former rail lines into public trails for biking and walking. When finished, the greenway will connect 75 of Baltimore’s neighborhoods, providing greater access to outdoor space for nearby residents.

“I feel like I’ve been a worker bee,” Benn said. “I’ve always just tried to do good work and keep at it. Cornell helped me do good design and bring the best I could to projects.”

Projects

Click to view project images full screen.

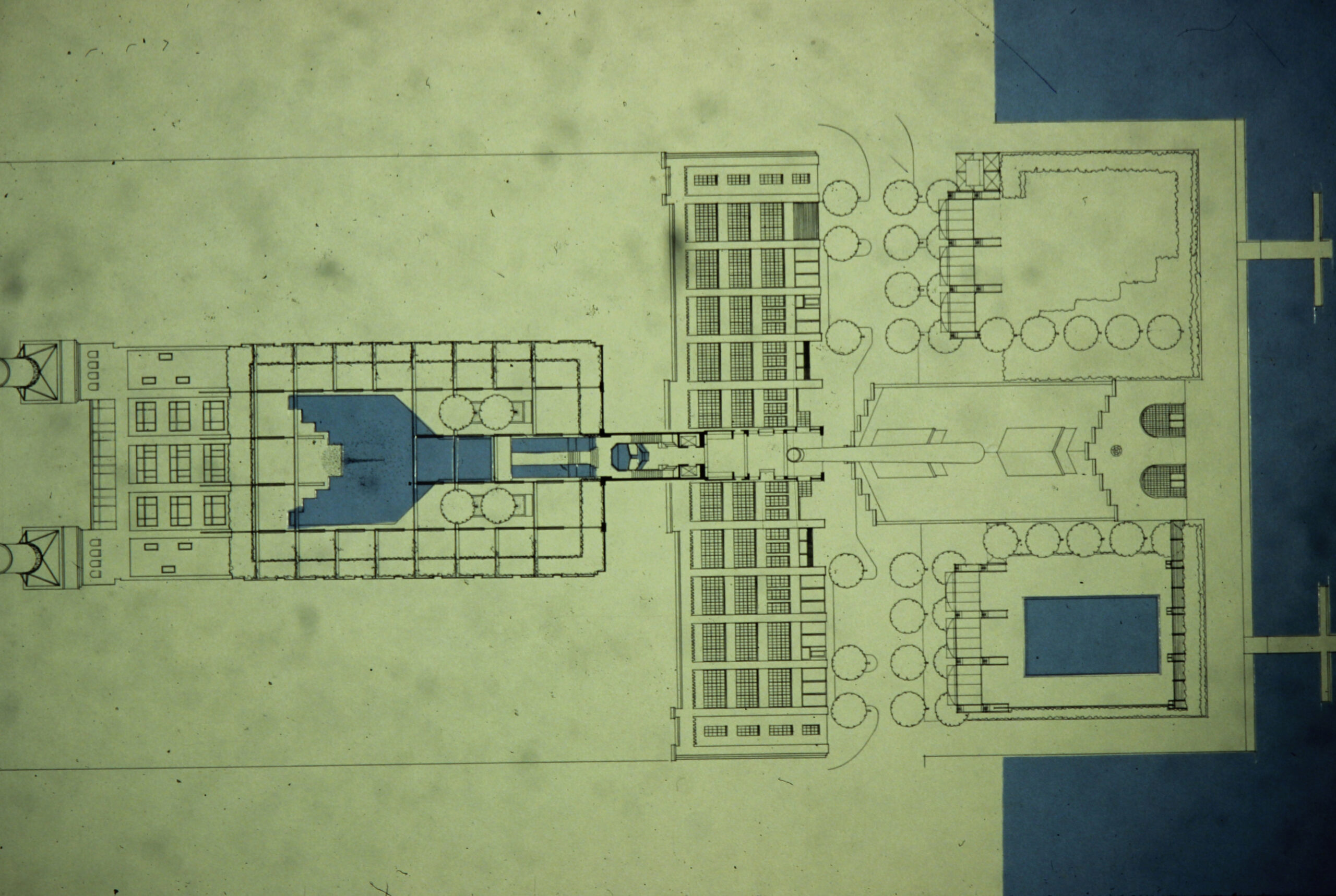

Tindeco Wharf Apartments

1987

Clipper Mill (2006)

2006

Enoch Pratt Free Library

2007

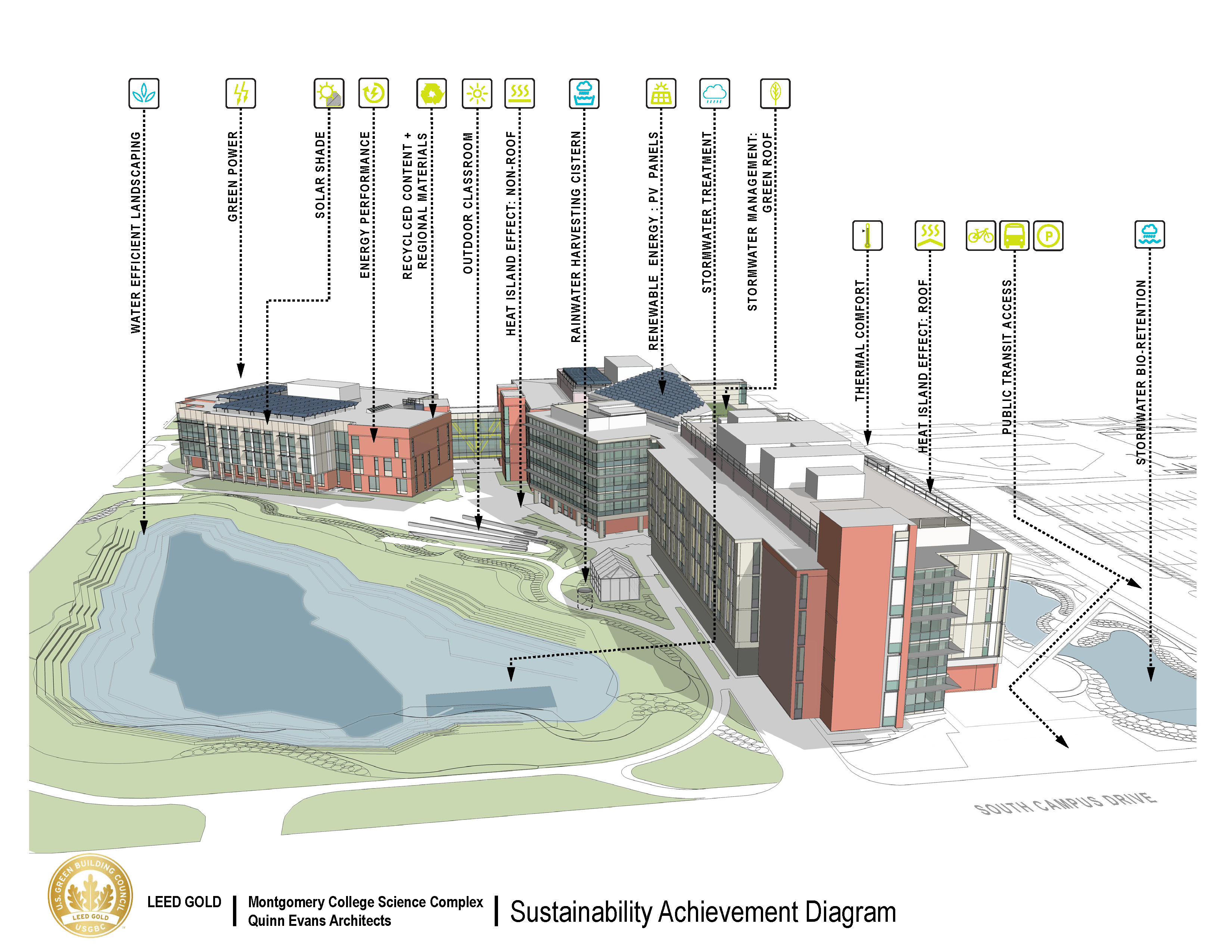

Montgomery College Science Complex (2016)

2016

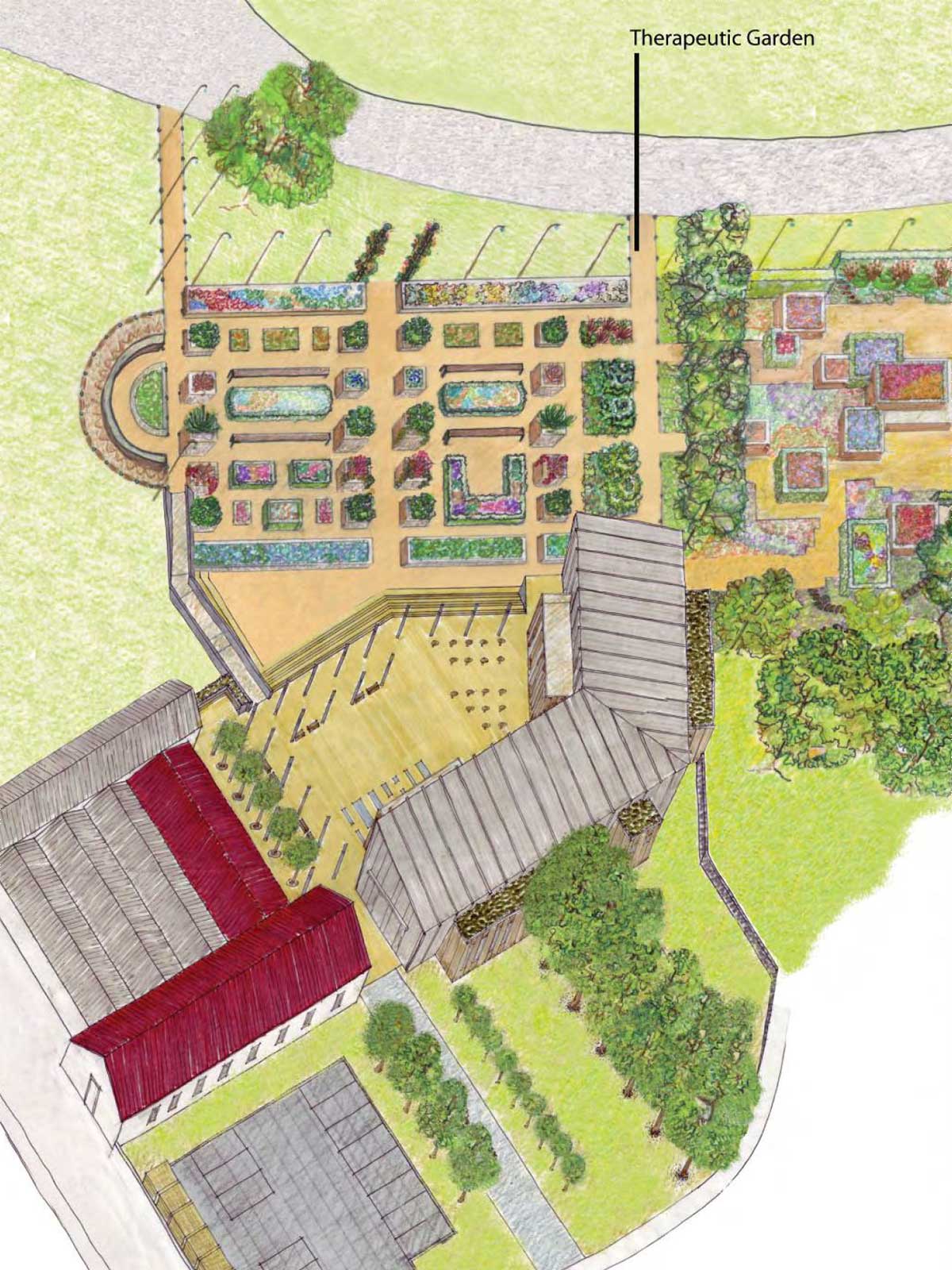

Pilot School

2016